The mind body divide

Almost every human culture on the planet holds that the mind is separate to the body. Modern physiology reveals that this ‘perception of an observer within’ is a characteristic of human brain, related to our ability to empathise with others; to plan and to imagine ourselves in the future and the past; and to use language to communicate as a ‘person’ with others. It is a mental artefact, an illusion like our occasional strong sense of déjà vu, intuition, or revelation.

In many ways this computer I am using is similar to another person. I’m writing this by dictating into a microphone. The computer recognises what I’m saying and writes my words for me. The same computer can read these words back to me in its own voice. Of course it does not understand what I’m saying about minds but it does understand the grammar and context of my words. It does hundreds of other very clever things as well. A primitive person (or even one from a century ago) would find this magical and might believe that there is a person hiding inside the box or communicating from another room.

But I have no illusion. I know that these abilities are a function of data interactions encoded as binary numbers and supported by a large collection of very ordinary physical devices connected in a particular way. As the number of devices compressed onto a CPU chip and into RAM (memory) has increased so has the computer’s ‘abilities’. We accept that computers are much better at mathematical processing or sorting tasks than we are and for many years it has been impossible for a human to beat an appropriately programmed computer at entirely logical games like noughts and crosses, drafts or Chinese checkers. But as speed and the number of active elements has grown to approach the number in a human brain, a computer can now consistently beat a Chess grand master or the best professional poker player; not because every possible game or cut of the cards has been ‘programmed in’ by some ‘super smart geek’, but because a computer can now be programmed to regularly ‘out think’, ‘out anticipate’ and ‘out bluff’ the smartest, most skilled humans at these games. This capability doubles about every two years (Moore’s Law). Further, new paradigms are in development that will make a computer more like a human brain and we can anticipate that computers will regularly outsmart the brightest humans in lots more areas in the very near future.

I have watched computers evolve, have built and programmed computers similar to this one and know in some detail how it works. I know that its role is to mechanically process the commands dictated by the interactions of program threads that in turn interact and respond to circumstance, memory, data and device inputs. But just as a completely mechanical player piano can still accurately reproduce George Gershwin, playing his music long after his death, so the functions and ideas are implicit in the arrangement of bits of data. The music is not in the piano or even the paper, it is ‘ideas’ encoded in the organisation and relationship between the holes in a paper roll. In a modern computer this organisation is itself flexible and subject to a succession of higher meta-level instructions. As I write this my computer’s four CPU are simultaneously running 85 processes and over 1,150 threads. Many computer functions are pre-programmed responses but their interactions are now so complex that they resemble ‘thought’. Like music on a roll, the ‘ideas’ are preserved in these relationships when I turn off and are reanimated when I turn my computer back on or move the data to another similar machine. Yet I am certain it stops ‘thinking’ when I remove the power. When I turn my computer off, the ideas are preserved, but there is no ‘mind’ that continues.

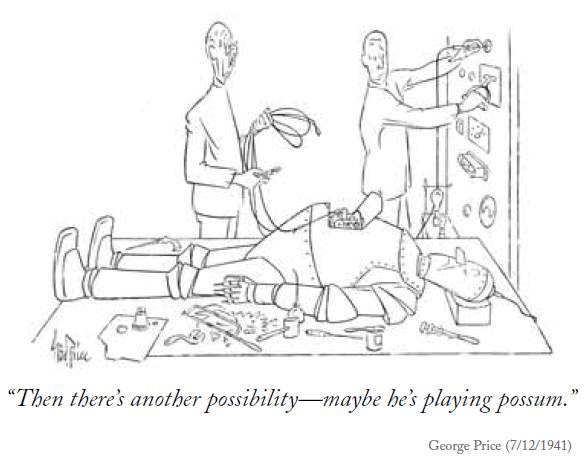

All cartoons from: The Complete Cartoons of the New Yorker

Similarly, we increasingly understand the general functioning of the human brain. We know that it is a collection of about ten thousand million neurons (cells), no longer vastly larger in number than transistors in a computer, but organised quite differently to present commercial computers. We know that a brain undertakes the ‘computer like’ functions, electrochemically processing memory and inputs, that we call intelligence. We know that when the brain is damaged personalities change and which areas of the brain are responsible for what functions. We understand how drugs or surgical interventions create illusions and delusions and we regularly put brains into a coma to minimise pain or enhance healing. We know how the brain inherits its characteristics from its cells; how these cells encode their functional instructions in DNA; and the process by which they inherit these instructions from their parent cell.

When the brain stops all perception ceases. There is no evidence whatever that the processes supported by the brain continue when the brain stops functioning. The brain in turn is reliant on the other major organs of the body for its functions. When its cells die even our memory is lost. There can be no ‘mind’ that keeps going after death.

Of course this does not refute the concept of an immortal soul, provided that one does not hold that this ‘soul’ continues to think, perceive sensation, or continue to behave as we did in life. For example, the idea: “that one might meet one’s dead mother and have a conversation; or reunite with one’s dead wife and continue marital relations”, is patently ridiculous if the soul is disembodied and is unable to process data: to think; see, hear, smell or feel them; or function physically.