Well, the Gillard government has done it; they have announced the long awaited price on carbon. But this time it's not the highly compromised CPRS previously announced by Kevin Rudd.

Accusations of lying and broken promises aside, the problem of using a tax rather than the earlier proposed cap-and-trade mechanism is devising a means by which the revenue raised will be returned to stimulate investment in new non-carbon based energy.

Taxation always boils down to 'robbing Peter to pay Paul'. In this case the Government knows who Peter is but they apparently have no idea, or too many, about Paul.

It is the very definition of administrative inefficiency to rob Peter to pay Peter. Thus any tax that requires offsetting payments to those taxed is poorly designed; administratively cumbersome and likely to be extremely inefficient; a bad tax.

The CPRS in its pure form, as originally conceived by officials of the Commonwealth Treasury and Ross Garnaut, achieved this redistribution through market mechanisms. Little intervention by government or the bureaucracy was required beyond defining the sectors covered by the scheme; setting the overall quantum (cap on carbon); and issuing permits equivalent to the cap.

For example (according to the Department of Climate Change): 'if the cap were to limit emissions to 100 million tonnes of CO2-e in a particular year, 100 million 'permits' would be issued that year.' Thus each tonne of CO2 emitted, by a firm responsible for emissions under the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, would require them to acquire a 'permit' from the market and surrender it.

Tradable carbon 'permits' would be bought and sold between investors in 'covered' sectors (as defined by the scheme) and would be priced according to the supply and demand. The CPRS would, in effect, be a widened version the of the existing tradable Renewable Energy Certificates scheme, this time based on carbon oxidised and released as CO2 rather than on 'renewable energy' generated.

But of course the economic and market purity of this scheme was immediately compromised by special pleading and the realisation that it would be at the cost of economic growth and present jobs; with any future jobs generated by the changes difficult to identify and hypothetical.

Thus trade exposed industry as well as little old ladies with air conditioners, struggling families and the disabled would be protected from its impacts.

Very soon Garnaut's pure and simple cap-and-trade mechanism was looking like a pakapoo ticket and 'CPRS' was an acronym for something obscene. It was quickly renamed the ETS (Emissions Trading Scheme).

Although Australia's contribution to world carbon is very largely due to our exports of coal, natural gas and aluminium, with domestic production of carbon infinitesimal in the total picture, we, like other developed countries can't to go to World forums and demand that other countries clean up their act unless we clean up our own.

Australians are already paying a high price for alternative electrical energy from wind and solar (and potentially, other renewable energy sources) through the Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) mechanism described in detail elsewhere on this website.

It was expected that the CPRS would replace this mechanism.

But it seems that Australian governments are incapable of implementing a straightforward scheme. With the CPRS we immediately saw a repeat of the goods and services tax (GST) farce, when special pleading had food and some other items removed from the impacts of the tax, creating distortions, favouring large food retailer concentration, and adding unnecessary complexity and cost.

Fundamental to any carbon reduction scheme is the need to increase the price of carbon based energy relative to alternative energy sources; thus encouraging investors to make the transition to lower polluting alternatives and households to implement economies and reduce their consumption of carbon sourced energy. There is an immediate problem if certain kinds of carbon sourced energy and certain types of consumer are exempted from these cost increases.

It is certain that any such exemptions will be highly economically distorting and might even lead to cheating (eg concerning eligibility for compensation) and black markets, as well as more serious criminal activity.

The correct way to deal with the negative impacts on the poor is to increase existing, already refined and tested, transfer payment methods, such as pensions, to compensate for the higher cost of living. Everyone, including the poor, needs to feel the impact of the higher prices as this is the very mechanism intended to encourage them to find alternatives to consuming, directly or indirectly, fossil based energy.

There should be no exemptions. But what is likely to be achieved?

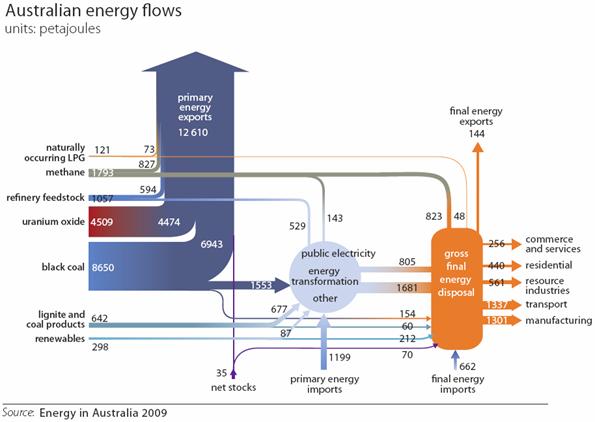

Commentators tend to focus on electricity. But electricity production represents only about a fifth of our total energy consumption. Direct consumption of carbon in industry together with the consumption of oil and gas for transportation and agriculture are the principal contributors to our combustion-sourced greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, land clearing, fires and the agricultural release of methane are significant contributors.

The only practical ways, at present, of providing petroleum-free transportation are electricity or hydrogen based. But in Australia around 90% of electricity comes from fossil fuels; and hydrogen used today is a by-product of the petroleum industry. Inefficiencies in generation, distribution, conversion and storage mean that converting transport to electricity in this country generally increases our greenhouse gas emissions. For electric transport to make a contribution to reducing our greenhouse emissions we need to obtain a much higher proportion of our electricity from non-fossil sources. Several European countries obtain up to 90% of their electricity from non-fossil sources and even the UK and US do a lot better than Australia.

Some suggest a solution rests in increased wind and solar generated electricity. For practical reasons, set out in the article on wind energy on this website, once equilibrium is reached, each new increment of wind energy requires three to four additional increments of base load and energy. In the case of solar at least five increments of additional base load energy are required for each increment. This is irrespective of the generation and delivery costs of wind and solar. At the present time this means a substantial ongoing investment in coal and gas in a ratio of at least four fossil fuel sourced electricity MWh to each renewable energy MWh.

This idealised case is further compromised in Australia due to the distances involved, our concentration in urban centres and the wide distribution of energy resources.

In the future advanced electricity storage mechanisms such as super-capacitors, batteries or flywheels or alternatively, heat or pressure storage mechanisms, might smooth the present mismatch between renewable energy production and consumer demand.

But at the present time there is no large scale energy storage solution with the exception of water pumped-storage, commonly used as a component of more sophisticated hydroelectricity generation schemes involving multiple linked storages like the Snowy Mountains Scheme. In relative terms these storages account for a tiny proportion of all energy delivered.

Worldwide hydroelectricity is by far the largest source of renewable electricity. Many countries are continuing to expand their hydroelectric generation with the construction of new dams and river diversions. But in Australia environmental and local interests have aligned to block large scale hydro electric generation since the completion of the Snowy Mountains Scheme. The present Greens leader, Bob Brown made his reputation subverting the last great hydroelectricity scheme in Tasmania.

But electricity production is already being addressed by a scheme designed to increase the utilisation of renewable energy; of which renewables, mainly hydroelectricity, already contribute 9%.

A carbon tax could well exempt electricity altogether on these grounds.

The following graphic shows the relative scale of energy flows in Australia.

Click the image to follow the link

Click the image to follow the link

To make a significant impact on World carbon dioxide production a tax could be applied to exported carbon. But there are many political, economic and practical reasons for NOT doing this.

Thus such a tax would apply only to the combustion (by oxidisation) of carbon in transport and industry.

In order to apply competitive neutrality and prevent the immediate demise of the basic metals, oil refining and chemicals industries, imported energy intensive goods and services would need to be caught to the same degree as domestically produced ones. Thus a low impact tax would most conveniently be applied in the same way as the GST to the final point of sale prior to consumption.

Again to what end?

As will be seen elsewhere on this website I believe that the only practical medium term alternative to burning coal and gas is a large and immediate investment in nuclear power to bring its contribution to our total energy mix to say, the European average, within two or three decades.

It is probable that the original cap-and-trade CPRS would have applied almost immediate economic incentives in this direction.

But for political reasons it is extremely unlikely that any Australian government will move in this direction under a carbon tax regime in which they can choose where to spend the revenue. Instead we are likely to see grants funded by a carbon tax to such things as electric cars, wind turbines, geothermal projects and solar panels; achieving nothing additional except further inefficiencies and waste.