Most commentators expect that traditional print media will be replaced in the very near future by electronic devices similar to the Kindle, pads and phones. Some believe, as a consequence, that the very utility of traditional books and media will change irrevocably as our ability to appreciate them changes. At least one of them is profoundly unsettled by this prospect; that he argues is already under way.

Today we see new technologies come and go within a few decades. Where has our local CD shop gone? Where do you buy a music cassette? When was the last time you saw a typewriter? Books as we know them have been around for almost two millennia. But they had little practical utility for the average person until movable type printing was invented, lowering their price and encouraging many more people to learn to read.

Newspapers have been around for less than 400 years; magazines containing illustrations a century less; and those with quality photographs (rotogravure and its successors) less than a lifetime. The time frame is narrowing. Now it is their turn to be replaced.

What have you done to my brain ma?

Jordan recently gave me a very interesting book to read: The Shallows by Nicholas Carr. Carr is a post-McLuhanite; although he would probably dispute this label. He argues, as did Marshall McLuhan in the nineteen sixties, that human beings have a 'plastic' brain that responds physically to its technological environment.

As I have pointed out elsewhere on this website [Read more…] when we learn a new thing our brain and nervous system stores this knowledge as new connections between neurones. Thus our physical body structure subtly changes.

As a baby grows the neurons in their brain and nervous system multiply and make new connections. This is directly analogous to the growth of their arms and legs and other body parts; except that neurones connect and multiply according to the baby’s experience. We call this physically encoded memory: learning; experience; skill; and habit.

It is this physical structure of cells and their connections that records what we can do, know and believe. This, more than the cells in our other organs, defines us as a person.

McLuhan extended this observation by considering a range of the tools that we learn to use; like learning to drive a car; or to read.

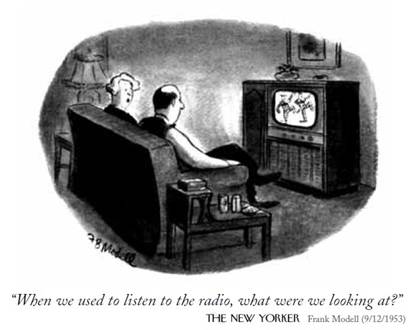

He examined a range of tools (media) from a light bulb to comics and the degree to which we relate to each. He employed the beatnik ‘jive talk’ of the mid 20th century to classify the tools with which we engage deeply, either intellectually or in terms of the senses engaged, as ‘cool’. Conversely the ones that we often ignore, with little personal engagement, he rather confusingly classified as ‘hot’.

Thus television, that requires us to use two senses, is ‘cooler’ than radio.

At the hot end of the scale he argued that a light bulb, encapsulates no other medium or message.

For McLuhan it was this engagement, that makes changes to our brain, that was the most important feature of our relationship to our tools (the media). Our physical bodies actually change in response to the media; according to how ‘cool’ they are. He disregarded the fact that the content too changes our brain. If you memorise Hamlet's soliloquy, you change the structure of your brain.

But McLuhan argued that the actual message carried is less important or perhaps irrelevant. Hence his famous aphorism: ‘The medium is the message’.

Today, in the light of our modern understanding of brain function, many regard McLuhan’s re-framing of our relationship to our tools as being no more than stating the obvious.

Elsewhere on this website I have described how one’s car can come to feel like one’s body; how we extend our perceptions to encompass our tools; our family and our extended environment [Read more…].

But McLuhan became a cult figure; pivotal to many of the revolutionary aspects of the nineteen sixties and seventies, influencing a wide range of thinkers and artists from Andy Warhol to Timothy Leary. It is said that he also revolutionised advertising; and was the father of today’s ‘media studies’. His unusual re-framing allowed many new ideas to develop and formed a jumping-off point for some that were quite crazy - like crazy, man!

McLuhan was prescient. When imagining something that would be cooler than television he foresaw and described: the personal computer; and the World Wide Web. He coined the terms ‘The Global Village’ and media ‘surfing’. He had no knowledge of how these might be implemented technically but argued that their advent was a technological inevitability.

Nicholas Carr restates many of McLuhan’s arguments. He in turn, asserts that compared to television, our interaction with computers and personal electronic devices is a big step on the cool side. And correspondingly the changes these tools make to our brains are much more significant. People who engage with computers and the World Wide Web become physically dissimilar to those who do not.

It's worth noting that similar criticisms of newspapers were made by the authors of books in the early 20th century as newspaper and magazine sales exploded with increasing literacy and the invention of celebrity and notoriety. The terms 'yellow press' and 'yellow journalism' were coined and writers like Aldus Huxley and DH Lawrence condemned popular newspapers as mere 'gossip sheets' that were likely to be harming their readers.

The preeminence of gossip and celebrity, including that around sport, as a means of selling media might be seen to have reached its ultimate conclusion in the recent scandals and demise of the 'News (Screws) of the World' in London.