Most commentators expect that traditional print media will be replaced in the very near future by electronic devices similar to the Kindle, pads and phones. Some believe, as a consequence, that the very utility of traditional books and media will change irrevocably as our ability to appreciate them changes. At least one of them is profoundly unsettled by this prospect; that he argues is already under way.

Today we see new technologies come and go within a few decades. Where has our local CD shop gone? Where do you buy a music cassette? When was the last time you saw a typewriter? Books as we know them have been around for almost two millennia. But they had little practical utility for the average person until movable type printing was invented, lowering their price and encouraging many more people to learn to read.

Newspapers have been around for less than 400 years; magazines containing illustrations a century less; and those with quality photographs (rotogravure and its successors) less than a lifetime. The time frame is narrowing. Now it is their turn to be replaced.

What have you done to my brain ma?

Jordan recently gave me a very interesting book to read: The Shallows by Nicholas Carr. Carr is a post-McLuhanite; although he would probably dispute this label. He argues, as did Marshall McLuhan in the nineteen sixties, that human beings have a 'plastic' brain that responds physically to its technological environment.

As I have pointed out elsewhere on this website [Read more…] when we learn a new thing our brain and nervous system stores this knowledge as new connections between neurones. Thus our physical body structure subtly changes.

As a baby grows the neurons in their brain and nervous system multiply and make new connections. This is directly analogous to the growth of their arms and legs and other body parts; except that neurones connect and multiply according to the baby’s experience. We call this physically encoded memory: learning; experience; skill; and habit.

It is this physical structure of cells and their connections that records what we can do, know and believe. This, more than the cells in our other organs, defines us as a person.

McLuhan extended this observation by considering a range of the tools that we learn to use; like learning to drive a car; or to read.

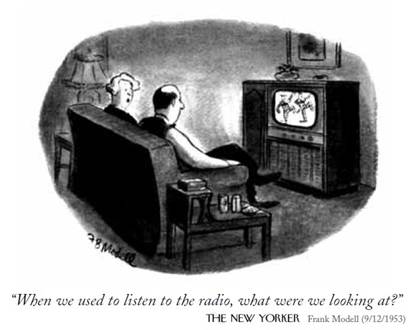

He examined a range of tools (media) from a light bulb to comics and the degree to which we relate to each. He employed the beatnik ‘jive talk’ of the mid 20th century to classify the tools with which we engage deeply, either intellectually or in terms of the senses engaged, as ‘cool’. Conversely the ones that we often ignore, with little personal engagement, he rather confusingly classified as ‘hot’.

Thus television, that requires us to use two senses, is ‘cooler’ than radio.

At the hot end of the scale he argued that a light bulb, encapsulates no other medium or message.

For McLuhan it was this engagement, that makes changes to our brain, that was the most important feature of our relationship to our tools (the media). Our physical bodies actually change in response to the media; according to how ‘cool’ they are. He disregarded the fact that the content too changes our brain. If you memorise Hamlet's soliloquy, you change the structure of your brain.

But McLuhan argued that the actual message carried is less important or perhaps irrelevant. Hence his famous aphorism: ‘The medium is the message’.

Today, in the light of our modern understanding of brain function, many regard McLuhan’s re-framing of our relationship to our tools as being no more than stating the obvious.

Elsewhere on this website I have described how one’s car can come to feel like one’s body; how we extend our perceptions to encompass our tools; our family and our extended environment [Read more…].

But McLuhan became a cult figure; pivotal to many of the revolutionary aspects of the nineteen sixties and seventies, influencing a wide range of thinkers and artists from Andy Warhol to Timothy Leary. It is said that he also revolutionised advertising; and was the father of today’s ‘media studies’. His unusual re-framing allowed many new ideas to develop and formed a jumping-off point for some that were quite crazy - like crazy, man!

McLuhan was prescient. When imagining something that would be cooler than television he foresaw and described: the personal computer; and the World Wide Web. He coined the terms ‘The Global Village’ and media ‘surfing’. He had no knowledge of how these might be implemented technically but argued that their advent was a technological inevitability.

Nicholas Carr restates many of McLuhan’s arguments. He in turn, asserts that compared to television, our interaction with computers and personal electronic devices is a big step on the cool side. And correspondingly the changes these tools make to our brains are much more significant. People who engage with computers and the World Wide Web become physically dissimilar to those who do not.

It's worth noting that similar criticisms of newspapers were made by the authors of books in the early 20th century as newspaper and magazine sales exploded with increasing literacy and the invention of celebrity and notoriety. The terms 'yellow press' and 'yellow journalism' were coined and writers like Aldus Huxley and DH Lawrence condemned popular newspapers as mere 'gossip sheets' that were likely to be harming their readers.

The preeminence of gossip and celebrity, including that around sport, as a means of selling media might be seen to have reached its ultimate conclusion in the recent scandals and demise of the 'News (Screws) of the World' in London.

Caught in the web

Another influenced by McLuhan was Howard Rheingold, a somewhat eccentric Californian writer who chronicled the advent of the computer and is still around today; being two years younger than I am. He lecturers at Stanford and UC Berkeley on 'the cultural, social and political implications of modern communication media'.

In his influential book ‘Tools for Thought’ (1985), Rheingold traces computing back to Ada Lovelace (Byron's Daughter) and Charles Babbage on one hand; and to George Boole through Bertrand Russell (referenced elsewhere on this website [Read Here...]) with Alan Turing, Norbert Wiener and his friend John von Neumann on the other. Rheingold interviews some, and researches other, contemporary players in the development of computing in the US. Like McLuhan he projects his observations forward to global networks and thinking machines; but unlike McLuhan he perceives the means by which this will be accomplished. It is a very interesting book that you can read on-line [Read it here…].

Reflecting my experience, I particularly liked his statement that one of the unofficial rules of computer programming (Babbage’s Law) is: ‘Any large programming project will always take twice as long as you estimate.’

I strongly recommend ‘Tools for Thought’ to anyone interested in the evolution of one of the last century’s most powerful technological ideas: the theoretical Universal Turing Machine. Today this idea has many more specialised avatars: like personal computers; the iPhone; the Xbox; almost all electronic media; gene sequencing machines; utilities management; traffic management; vehicle and aircraft control computers; and of course the Internet.

Again Nicholas Carr reprises much of ‘Tools for Thought’. Carr is very worried by these potentially inevitable trends. He believes that the changes to our brains that these new technologies are making are potentially problematic.

In particular Carr believes that our ability to read books has been compromised by the use of the Web. He distinguishes deep reading from shallow reading. The deep reading is full engagement with a book where we avoid or ignore distractions. Shallow reading is when we skim and are distracted by hyperlinks, footnotes and asides. We just want to know the gist of the story.

He says that the Web teaches shallow reading and this could lead to people being unable to read books deeply.

This is not a threat as long as people continue to exercise their conventional book reading skills but he accepts that new reading devices like the Kindle and iPad make libraries of books available at very low cost and it will not be long before simple economics and convenience makes the conventional book a specialist collector’s item or museum artefact.

Although ostensibly presenting pages in the same way as a book, these devices and the books that have been digitised are replete with hyperlinks; instantaneous references to other media; and the potential to search and flip; which he says are distracting and lead to shallow reading.

Carr is concerned that more and more people are using the Web, undergoing corresponding physical changes in their brain, making them unable to consume traditional media and are thus becoming addicted to shallow electronic media. He is worried about the ephemeral understanding that he believes this media engenders. He says that many people can no longer concentrate long enough for full comprehension; or remembered understanding.

Worse, to overcome shortening attention spans writers for the media are said to be using simpler and simpler concepts and breaking their content of into short paragraphs, sound bites and movie snippets. It's like government agencies being obliged to use 'Daily Telegraph' English in press releases, communiqués and official letters; and no polysyllabic words or Latin please. Soon it feeds on itself. The language itself is progressively dumbed-down.

While it is hard to disagree with some of these points, I take issue with one or two.

First, as many of us know the Web encourages more concentration in some new areas. Playing some electronic games requires very high levels of concentration. Those of us who write computer programs know about getting ‘in the groove’ when all distractions are ignored or intolerable; giving programmers a reputation for being rude. Of course the same has always applied to many crafts-persons and anyone doing complex, mentally challenging tasks.

Second, skimming and speed reading is not new; it's the way most people read newspapers and magazines. The Web actually makes this process more efficient.

When a book sets out important information; as we might find in a university text on almost any specialist subject, it is seldom read continuously from beginning to end like a novel. Often during research several books are open at the same time. The same applies to histories and biographies, when a reader may want to check a fact or look at another reference. Again computers and the Web facilitate this kind of reading.

For example this website is set up with a mixture of long and short articles split into pages; that can be skimmed or read in some depth if desired. This must be a reasonably good formula as many readers return many times. You can see how many readers are currently on the site on left of the Home page. The current site statistics from Google Analytics can be seen here... These give a good indication of interest in a particular page and the geographical origin of readers but significantly understate the readership according to visits and hits recorded on the site.

In contrast to websites and text, reference or history books, novels are generally written to be read sequentially as written; sometimes didactically or proselytising some cause or social change; but more typically simply to entertain the readers, by providing escapism, recreation and/or the distraction of fantasy. Few actually warrant the very high levels of immersion, memory or even comprehension that Carr feels might be lost by skimming and jumping about between references.

While readers certainly do get immersed in novels, this escapism might be seen as a similar undesirable addiction to the one he fears in respect of electronic media; indeed historically many critics made exactly this point. Being a 'book worm' has not always been socially acceptable.

Books change our brains too; and unless well written and intellectually expanding, not necessarily for the better.

I feel my mind going

Perhaps the greatest danger presented by the World Wide Web is its potential to become intelligent in some uncontrollable way. This is of course the very stuff of science fiction.

One of the most memorable science fiction scenes is in Stanley Kubrick’s movie ‘2001 A Space Odyssey’ (1968), based on the book by Arthur C. Clarke. While on its way to one of Jupiter’s moons a HAL 9000, the ship's intelligent computer (HAL is IBM shifted alphabetically one letter forward), has gone mad (perhaps) and murdered almost everyone on board. Dave the remaining crew member is progressively removing cards from HAL's brain. HAL plaintively pleads for him to stop: ‘Dave, my mind is going… I can feel it... I can feel it’ then begins to sing ‘Daisy’ in a ‘machine voice’; a little program that was installed on many computers of the day. It is just a computer again, its intelligence has gone.

Unlike many, I am in no doubt that machines will think someday; probably not too far into the future. After all, as others have remarked, I’m a machine, a construct comprised of a structured colony of physical cells; and I think.

In his book, The Shallows Nicholas Carr dedicates a chapter to the computer program Eliza; that Emily and I played with at the Powerhouse Museum many years ago. This simple program went some way towards passing the Turing test for intelligence:

| A human judge engages in a natural language conversation with one human and one machine, each of which tries to appear human. All participants are separated from one another. If the judge cannot reliably tell the machine from the human, the machine is said to have passed the test. In order to test the machine's intelligence rather than its ability to render words into audio, the conversation is limited to a text-only channel such as a computer keyboard and screen. |

Some people were in fact tricked into believing that they were talking to an intelligent being; but of course the program was demonstrably not intelligent. It simply modified their own input and fed it back to them; much as a fortune teller or a Freudian psychiatrist might.

I remember the children found it amusing to ask Eliza questions like 'is there a God' or 'will I get married', but I don't think too many were fooled into thinking that there was a person or other intelligent being behind the screen. Now you can do this on line: Talk to Cleverbot here! where apparently people do think they are talking to a person; despite assurances that they are not. I'm not convinced. Here is a recent exchange with me (it had already complained that I did not love it) :

| Where is God? |

| Everywhere. |

| How can that be? |

| Relevence is reletive. |

| From what perspective? |

| From the one that did not love me. |

I have said elsewhere the, getting old, computer I’m using at this minute is more convincing. It would easily have convinced a person of a hundred years ago that another person was hiding somewhere. I’m talking to it, using a microphone that they would not have recognised, and it’s typing my words. Quite often it misunderstands me and types something that it 'thinks' sounds right and that it 'thinks' makes sense, so that I have to tell it to change that bit; which it does. Of course, like much older machines, it also fixes spelling and suggests changes in grammar. If I want it to, it will read back what I’ve written – or anything else I nominate in its own voice. It will change applications and make a phone call, send a fax, or an email if I ask it to. And it plays chess at least as well as I do.

In many computer games very lifelike human figures undertake entirely independent actions, the details of which are unknown to their programmer/creator, as they depend on the unique circumstances of a particular game, that in turn, depend on the actions of their human player or opponent. Each game is unique and circumstantial.

So simulating a human in a general way proves nothing about underlying intelligence.

There is no rule that says human intelligence is the only standard that all intelligence must follow. Building a simulation of a human brain would only be interesting for the insights it gave into the broad principles involved. And we have more than enough humans already.

We know that a human brain is a collection of about ten thousand million neurons connected in a complex web and we know that this complexity gives rise to emergent intelligence.

The World Wide Web is still several thousand million connections short of this number and the interconnection between nodes too ephemeral to be of any concern; yet. But we are only about ten years in, so far. Cloud computing is in its infancy and the Web interconnection engines, that might facilitate such a dawning of intelligence, are still very tentative. Google is well aware of this potential and the company is said to have Web intelligence as a medium term goal.

Let’s hope that the changes the Web is making to our brains helps us to be come more intelligent and capable; rather than dumbing-down everyone to some lowest common denominator.

But more, let’s hope the Web remains benign; once it, or computers attached to it, can make independent decisions and act on evaluations based on its, or their, own experience. It already knows a lot more than I or you do.

Richard