Christianity

The orthodox Christian belief, based on Biblical study, is that when we die, we await the Second Coming, when Jesus will return to judge the quick (living) and the dead. On this day, those that pass judgment will ascend to heaven to live eternally and those who have failed judgment will continue, without grace, in everlasting torment.

Christianity, as we know it, started with its adoption by the Roman Empire as the official (but not only) religion. This took place progressively from the conversion of the emperor Constantine in 313 AD and the subsequent Council of Nicaea in 325, the first ecumenical council. Progressively Christianity was then enforced and other religions excluded. For the next thousand years a variety of saints, thinkers, warriors and politicians developed the religion so that by 1600, the power, glory and a huge wealth, that we see evidence of today in Rome and the great Christian cathedrals of Europe, had accumulated.

But by the 15th century inexpensive printing had become available. This encouraged many more people to learn to read and in 1455 the first cheap printed Bible was published by Johannes Gutenberg, in Mainz, Germany. Biblical scholars quickly discovered that serious inconsistencies had developed between Church teaching and the Bible.

Among these was the status of the dead. It is clear from the New Testament that St. Paul and others believed that the second coming was imminent and that the dead had little time to wait before they would be judged. But when over a thousand years had passed and in numerous generations had lived and died, the Church began to teach that people could proceed to heaven in a reasonable time, after a period in Purgatory. Purgatory has no biblical authority but was a conveniently invented place where the souls of the dead were supposedly prepared for heaven. This preparation could be enhanced or shortened by the purchase of indulgences from the Church.

Biblical scholars also noticed that in the intervening years the Church had invented a number of additional sacraments, like Extreme Unction, to enhance the status of the Priest in the lives of the people, and concurrently, could be charged for to further enhance the wealth of the Church.

In 1517 Martin Luther, an ascetic Augustinian monk and Biblical scholar, incensed by the practice of indulgences, nailed 95 ‘theses’ in Latin to a church door in Wittenberg. In addition to railing against indulgences, he asserted the primacy of the Bible in theological matters and the ability of every Christian commune with God directly, without the need for a church to intercede. This was an idea whose time had come and within the extraordinarily short period of about two months, these ’95 articles’ had been translated into several languages, printed widely and distributed throughout Europe; sowing seeds of the protestant revolution.

At its origin Christianity was a somewhat militant Jewish sect, specifically concerned with the slaughter of lambs the Passover and the excessive power of the Temple priests. According to the Vatican website it had been described by the Emperor Nero as ‘a strange and illegal superstition’ and blamed, amongst other things, for the burning of Rome (AD 64). Tacitus the contemporary Roman historian in his report of the ‘Great Fire’ mentions that Christians confessed to the arson, possibly under torture. Nero treated Jews harshly and Jewish uprisings that started during his reign were put down with great force, culminating after Nero’s death, in thousands being crucified at the Siege of Jerusalem (AD 70). Christian martyrs from this period were entombed alongside other Jews. Tacitus, writing in AD 116, describes Christianity as ‘a most mischievous superstition’, originating ‘in Judaea, the first source of the evil’, and spreading to Rome, ‘where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular’.

Terrorists; martyrs; vitriolic journalism; it all sounds very familiar, doesn’t it?

The historical Jesus was an ordained Jewish Pharisee and as a result, Mathew (Jewish period – written around 38 AD) confirms that the Old Testament Torah is the law; and the ‘Sermon on the Mount’ (Mat 5-7) consists mainly of a reiteration and elaboration of Old Testament laws.

Amongst these laws was the Jewish second commandment (prohibiting images). This was conveniently removed when Christianity became the official Roman religion to allow images of the emperor to be juxtaposed with those of the infant Jesus and Mary, as can be seen today in the oldest remaining Christian church and the World (Hagia Sophia) in Istanbul (well worth a visit). To get back to Ten Commandments, the Roman Church split the last commandment, about coveting your neighbour’s wife or house.

Adherence to the original second commandment then became a test that distinguished Christianity from Islam and Judaism. From about 900 onwards when Christians regained Iberian territory from the Moors, their first act was to desecrate their holy sites by mounting Christian or even pagan images within them. This is best seen in Southern Spain and Portugal (also worth a visit). Often additional religious tests were applied, to weed out non-Christians like a requirement to eat pork, possibly followed by trial by the Inquisition (like trial by ‘the saw’ where the inquisitee is hung upside-down legs apart then slowly sawed in half through the crotch – as the blood runs to the head they could be kept alive for hours, or simply disembowelled alive). Officially, between 1560 and 1700 there was a total of 49,092 trials registered in the archive of the Suprema (mainly against heresy, Moors and Jews, in that order), but unofficially just one Inquisitor, Tomas de Torquemada (b1420) is accredited with over 200,000 tortured and killed. These numbers have since been by equalled by Slobodan Milosevic’s ethnic cleansing of Muslims (with a quarter of a million dead) and of course put into the shade by Adolf Hitler who reportedly ordered the death of six million Jews, with the real or imagined blessing of the Vatican.

But with new and more accurate biblical translations the Protestants rediscovered the second commandment: ‘Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth: Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the Lord thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me; And showing mercy unto thousands of them that love me, and keep my commandments.’ (Exodus 20:4-6). This was interpreted as a prohibition on worshipping images or using images during worship.

It also suggested that heaven was not of this earth. This change corresponded with the Copernican revolution in astronomy, when it was realised that the Earth revolves about the Sun and subsequently that the Sun is but one of trillions of stars. Apart from occasioning the destruction of a great number of works of art, not a few books, and some unreformed Christians by the Protestants, the rediscovery of the second commandment contributed to the reappraisal of the physical reality of heaven itself.

Thus the naive, perhaps pre-Christian Roman view put to the simple people and children for over a thousand years: that Heaven and even Purgatory were physical places, located in the sky somewhere above the earth, became untenable. Now educated Christians needed to believe instead that heaven is ‘other dimensional’ and outside this physical universe.

The Bible is very vague or contradictory about what happens to you when you die. As mentioned above we learn in Revelations that the tribes of Israel are present and it seems that this is a real physical presence. But this probably needs to be judged in terms of the beliefs of the day, a blend of Egyptian, Roman and Greek thinking about the life hereafter that equates quite closely to the Hollywood interpretation of the happy hunting ground of indigenous Americans (like Russell Crow in Gladiator).

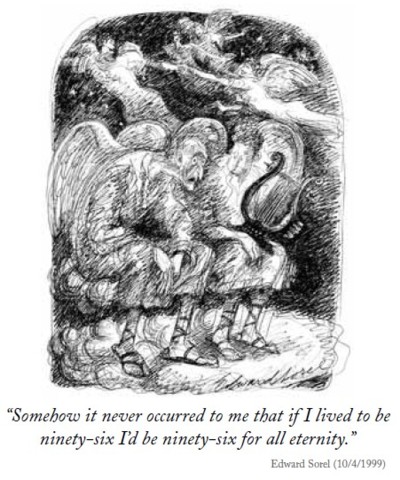

Today Western thinking is heavily influenced by Hollywood and nineteenth century romantic literature. We have all seen a movie where the ghostly figure rises from the dead body. In this view the soul leaves you in the state you were in when you died and passes into the ether. Thus you arrive in heaven as a ghost, a young or decrepit old person, as when you died, and will be in that state for eternity. So, each year we say of our dead soldiers: “age shall not weary them nor the years condemn”, implicitly acknowledging the Viking and Roman view running through our literature and culture, that it is better to die in battle than of old age. You will then spend eternity a virile young man, too young to have accumulated many sins; perhaps in the company of similarly aged young women.

These days, for most, this is a mere romantic, poetic fancy as is illustrated by our condemnation of the same idea in the Islamist suicide bombers of today.

A problem with this view, for many, is that so many people now live until infirmity and loss of intellect; not a pleasant prospect for all eternity; and hardly a happy reunion with a long dead, much younger partner. Obviously regressing to a twenty-year-old is no good either, as then you may not have met your partner nor had those children.

An alternative is that your pure soul or essence goes to heaven. In this view the soul has no age. It is immortal and has no permanent bodily characteristics; it simply occupies a physical body from conception to death and then passes on to heaven. It does so without any physical attributes, like aging, and has no physical needs. In this view, there is no food, clothes, exercise or sex in heaven (but there may be pain in the other place). This is more like a Buddhist view where a soul can go to another person or even an animal perhaps with no perception of where it has been. I, for one, have no recollection of a previous existence.

It is evident that the concept of a soul changes from time to time and this suggests that it is a human fancy.