Introduction

This is the story of the McKie family down a path through the gardens of the past that led to where I'm standing. Other paths converged and merged as the McKies met and wed and bred. Where possible I've glimpsed backwards up those paths as far as records would allow.

The setting is Newcastle upon Tyne in northeast England and my path winds through a time when the gardens there flowered with exotic blooms and their seeds and nectar changed the entire world. This was the blossoming of the late industrial and early scientific revolution and it flowered most brilliantly in Newcastle.

I've been to trace a couple of lines of ancestry back six generations to around the turn of the 19th century. Six generations ago, around the turn of the century, lived sixty-four individuals who each contributed a little less 1.6% of their genome to me, half of them on my mother's side and half on my father's. Yet I can't name half a dozen of them. But I do know one was called McKie. So, this is about his descendants; and the path they took; and some things a few of them contributed to Newcastle's fortunes; and who they met on the way.

In six generations, unless there is duplication due to copulating cousins, we all have 126 ancestors. Over half of mine remain obscure to me but I know the majority had one thing in common, they lived in or around Newcastle upon Tyne. Thus, they contributed to the prosperity, fertility and skill of that blossoming town during the century and a half when the garden there was at its most fecund. So, it's also a tale of one city.

My mother's family is the subject of a separate article on this website.

The McKie Family - in the mists of time

The Mc-Aodhs, sons of Aodh, originated in Scotland. The name is said to derive from the pre-Christian god of fire (Aodh) that was once something guttural, like: 'agh'. There are several variants on the spelling. The most dominant spelling today is McKay.

The 'McKie' spelling obviously goes back to a single couple, perhaps in the Elizabethan period, and is probably due to a mutation in the pronunciation. As the language has evolved so did the pronunciation of the name. McKie, spelt our way, is the closest phonetically to the most common pronunciation: 'ie' as in 'pie'. Perhaps its an Irish version but it might have gone the other way.

In his book Scots-Irish Links 1575-1725 David Dobson lists several McKies in Ireland who travelled to and from Scotland Kirkcudbright and Wigtonshire between 1643 to 1690. That part of Scotland has very close Irish connections and it's from Ireland that Christianity was reintroduced to Northern England in the medieval period. For more information go to the chapter on Northern Christianity in my travels to Northern England.

According to another reference the spelling is Scottish (Trials of Scotland, 1486 - 1660) where a Mackie was tried for, and acquitted of, 'slaughter' in 1606. Mackie is another related line of spelling pronounced 'mack-ee'. My mother's aunt Isobel married a Scotsman, Andrew Mackie, and two of her favourite cousins (Thompson and George) and a number of their offspring have that name.

By at the turn of the 18th century the two main clusters of people with the name McKie were in south western Scotland, with another group, probably about half the size, immediately across the water in Ireland.

This spelling confusion is a constant annoyance to members of our family. We are constantly telling people who try to write it the wrong way: "It's 'ie', as in 'pie'? Why are you trying to spell it 'ay', as in 'hay'?" And as to the other common mispronunciation: "In English 'ie' is not pronounced 'ee', as in see, or McKee."

The name, spelt our way, is not particularly common, even in Scotland or Ireland.

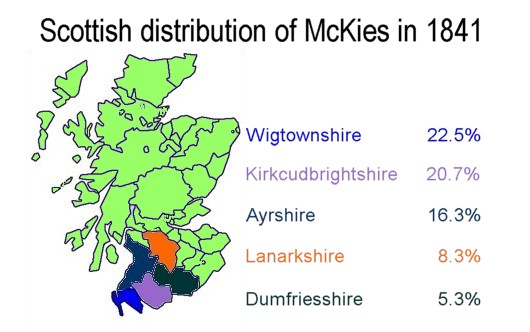

At the first relatively reliable and comprehensive Census of England, Wales & Scotland in 1841 there were just 1,282 people in Britain named McKie, 86% of them in Scotland, with around 70% of those in one big cluster around Kirkcudbright. We have most of their names and ages and even know a little of what they did. That part of Scotland is rural with very few significant towns. Just Dumfries to the east and Ayr to the north. Almost all were farmers or farm labourers. A handful were tradespeople (bookseller, grocer, tacker). A few professionals (Gas Manager, Inspector of the Poor) and others semi-skilled labourers (dyker, carter etc).

We can guess that there were around 600 McKies in Northern Ireland.

There were less than 200 individuals in England. The biggest group was in Lancashire. Many of these McKies had recently hailed from Ireland, attracted by the prospect of jobs in the 'dark satanic mills' or perhaps fleeing the potato famine. The next largest group, in Northumberland and Durham, hailed almost entirely from south west Scotland.

| Location | Country | Number | Percentage |

| Lancashire | England | 67 | 5.2% |

| Northumberland | England | 29 | 2.3% |

| Cumberland | England | 18 | 1.4% |

| Durham | England | 18 | 1.4% |

| Surrey | England | 10 | 0.8% |

| Westmorland | England | 10 | 0.8% |

| Shropshire | England | 8 | 0.6% |

| Yorkshire | England | 8 | 0.6% |

| Kent | England | 4 | 0.3% |

| Cheshire | England | 3 | 0.2% |

| Cornwall | England | 2 | 0.2% |

| Nottinghamshire | England | 2 | 0.2% |

| Individuals/travellers | England | 5 | 0.4% |

| Wigtownshire | Scotland | 289 | 22.5% |

| Kirkcudbrightshire | Scotland | 266 | 20.7% |

| Ayrshire | Scotland | 209 | 16.3% |

| Lanarkshire | Scotland | 107 | 8.3% |

| Dumfriesshire | Scotland | 68 | 5.3% |

| Renfrewshire | Scotland | 30 | 2.3% |

| Midlothian | Scotland | 23 | 1.8% |

| Aberdeenshire | Scotland | 20 | 1.6% |

| Stirlingshire | Scotland | 14 | 1.1% |

| Dunbartonshire | Scotland | 11 | 0.9% |

| Fife | Scotland | 10 | 0.8% |

| Haddingtonshire (East Lothian) | Scotland | 10 | 0.8% |

| Cromarty | Scotland | 9 | 0.7% |

| Perthshire | Scotland | 9 | 0.7% |

| Banffshire | Scotland | 8 | 0.6% |

| Forfarshire (Angus) | Scotland | 6 | 0.5% |

| Moray | Scotland | 2 | 0.2% |

| Individuals/travellers | Scotland | 6 | 0.5% |

| Glamorganshire | Wales | 1 | 0.1% |

| Every McKie in the 1841 Census | 1,282 | 100.0% |

We have long known that each of us inherited the colony of cells that each of us calls 'me' from our natural parents. Likewise, they did from theirs, and so on, in such a way that there is no possibility that any two fraternal siblings can be identical. Unless you shared the same first cell you and your brother or sister are certain to have a different mix of your grandparents' genes. But there are two exceptions to this mixing and these provides two particular lines we can follow back along our line of decent like a thread back to the common ancestor of everyone, thanks to new understanding of this process, just within my lifetime, and advances in computer technology.

One is the genome of the mitochondria in the cells of every one of us. These come exclusively from our mother, her mother and so on back to the last common female ancestor. Our fathers have nothing to do with that.

The other, like a family name, is the Y chromosome that each boy inherits exclusively from his father. His mother has no input to that little part of his genome that makes him male or his sister female. That little part came from a single male spermatozoon of his father's; that successfully fertilised his mother's egg-cell (ova); that multiplied to become him.

Thus, the sex of a child is entirely due to which of the father's sperm successfully fertilises the ova. Numerous studies (eg) have found no discernible difference in speed or size or strength or persistence between spermatozoa bearing a Y or an X chromosome. So, it is untrue, and 'an old wives' tale', that the mother can predetermine the sex of her baby in some way, for example by timing copulation or altering the environmental conditions in her womb.

But it's possible that a father can. On average more boys are born than girls indicating that men produce slightly more male than female sperm. As more boys are born at the end of wars it has been speculated that men can hormonally influence their sperm gender balance. So perhaps individual men of a particular age do produce a lot more male sperm while others produce more female - this is untested. Thus, any bias towards one sex or another is entirely up to the father. Maybe exercise or diet or stress or injury or even frequency of ejaculation can be factors? Yet the biggest factor remains chance. Like the flip of a coin each event is independent of the last; so six girls or boys in a row is not particularly unusual.

All things being regular, in our culture, a family name and a boy's Y chromosome go together. So, all McKie males should be able to trace their Y chromosome back to the original man of that name: McKie begat; McKie begat... And all McKie males of that name should share the same Y chromosome.

| DNA Ancestry Report of Richard McKie The following Y chromosome SIR marker profile for Richard McKie has been obtained through PCR analysis of Y-DNA SIR loci. Y-DNA is passed down from father to son along the direct paternal lineage. All males who have descended from the same paternal lineage (same forefather) as Richard McKie are expected to have exactly the same or very similar Y-DNA SIR marker profile as Richard's profile shown below. If two males have completely different Y-DNA SIR marker profiles, it will conclusively confirm that they did not descend from the same paternal lineage, regardless of a common surname.

|

||||

| DYS385b | 14 | |||

| DYS388 | 12 | |||

| DYS389i | 13 | |||

| DYS389ii | 30 | |||

| DYS39O | 24 | |||

| DYS391 | 10 | |||

| DYS392 | 13 | |||

| DYS393 | 13 | |||

| DYS426 | 12 | |||

| DYS437 | 15 | |||

| DYS438 | 12 | |||

| DYS439 | 12 | |||

| DYS447 | 25 | |||

| DYS448 | 19 | |||

| DYS460 | 10 | |||

| GATAH4 | 13 | |||

| YCA11a | 19 | |||

| YCA11b | 24 |

In 1841 our direct (Y chromosome) line of McKies and their families accounted for just six of the 29 McKies in Northumberland and probably quite a few more in Ayrshire.

|

|

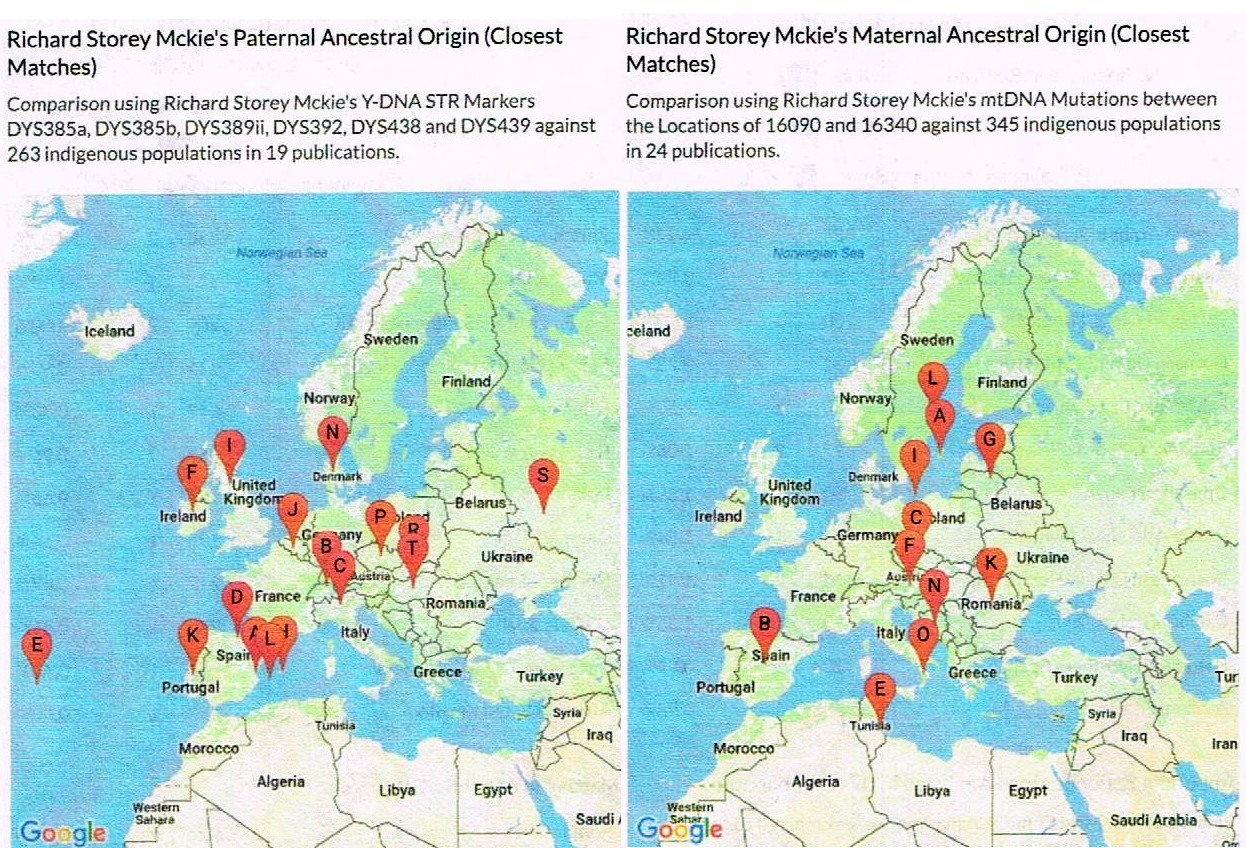

My Y chromosome provides much more ancient knowledge.

Description of Richard McKie's predicted Y-DNA Haplogroup: Y-DNA Haplogroup R1b |

|

The defining mutation for individuals who belong to Y-DNA Haplogroup R1b is a positive test for SNP marker M343. The man who founded Y-DNA Haplogroup R1b was born approximately 15,000 to 20,000 years ago prior to the end of the last Ice Age in southern Europe, Iberia or West Asia. Members of Y-DNA Haplogroup R1b are believed to be descendants of Cro-Magnon people, the first modern humans to enter Europe. When the ice sheets retracted at the end of the ice age, descendants of the R1b lineage migrated throughout western Europe. There is recent fossil and DNA evidence that the Cro-Magnon people may have interbred with the larger-brained and more robust but less communal Neanderthals. Today, Y-DNA Haplogroup R1b is found predominantly in western Europe, including England, Ireland, and parts of Spain and Portugal. It is especially concentrated in the west of Ireland where it can approach 100% of the population. Y-DNA Haplogroup R1b is a dominant paternal family group of Western Europe. It can also be found in lower frequencies in Eastern Europe, Western and Central Asia and parts of North Africa and South Asia. This Y-DNA Haplogroup contains the well-known Atlantic Modal STR Haplotype (AMH). AMH is the most frequently occurring haplotype amongst human males with an Atlantic European ancestry. It is also the haplotype of Niall of the Nine Hostages, an Irish King in the Dark Ages who is the common ancestor of many people of Irish patrilineal descent. Elsewhere the Genetic Genealogy website tells me that my version of the Y-DNA Haplogroup R1b, shared by almost all McKie males, is most commonly found in the people of Ireland and Spain. Although it is nothing to do with this essay, my version of mtDNA Haplogroup H, inherited from my mother, her mother and so on, is most commonly found in the people of Central Portugal and the Pyrenees. But it is found throughout Europe, including Russia and Turkey, and among the Druze population largely found in Syria and Lebanon. Now I realise why I felt less conspicuous in Syria than in other parts of the Middle East. Source: Genetic Genealogy - my additions/comments in blue |

As I have no reason to believe that mine is not a true copy of the McKie Y chromosome as far back as this McKie male over 230 years ago, my haplogroup is informative in another way.

The nearest Y chromosome relative in the Genetic Genealogy database is not called McKie at all but Geddes. He and I have a common male ancestor 17 or less generations back. I initially thought that a genetic generation was about 25 years but more recent investigation has found that historically a male generation was closer to 35 years and a female generation around five years less (30 years), on average. Thus, Ryan John Geddes' and my common ancestor probably lived during the 15th century, very likely in Scotland. This was after the Scottish Wars of Independence, during the Stewart Dynasty, or perhaps as late as the Scottish Reformation or the Scottish Enlightenment.

There's a McLean within 22 generations but the nearest McKay listed and I share a male ancestor within 35 generations, who lived during the 13th century. Of course, there may be many closer who have not used this DNA analysis service.

So if there has been no irregularity in Ryan Geddes' ancestry or mine, like stray roosters in the hen coop, we can assume that the change in spelling to McKie occurred somewhere after the middle ages.

Using various on-line resources, I have been able to trace the McKie line back six generations to Alexander McKie born around 1781 in Scotland. He was an agricultural labourer married to Jannet Sloan. They are the best match from census birth and marriage records as parents of William McKie who I know was my ancestor and was born in 1804. If these are his parents it means he came from in Girvan, Ayrshire in Scotland.

Just two generations back I have a Domville line, my father's mother, that could be my nearest claim to being in any way 'noble'. See my Grandmother's Family later on.

My Ancestors - into the 19th Century

It seems that my great great great grandfather William McKie left Scotland for England as a young man and found work in Gateshead, Durham just across the Tyne from Newcastle. Margaret (probably Davidson) was an older woman. She was also born in Scotland. They were married in Gateshead, in the parish of St. Mary, on the 21st of April 1828. She was 31 and he was just 24.

It's probable that she was a widow because, according to the 1841 census, her eldest daughter Elizabeth, was born three years before their marriage. Their next daughter Jane, was born in 1831 followed by Alexander McKie in 1833 and then James McKie in 1835.

Like other members of our family since, they lived far distant from their parents and so lacked the support and family lore that grandparents can provide. The trip back to Ayrshire was over a hundred miles, a two days journey by coach or horse, longer on foot.

It would be another eight years before the Newcastle & Carlisle Railway completed the distance to Carlisle. In any case early passenger trains on the completed sections were horse-drawn and not a lot faster than a coach. The first connecting steam train service to Ayr would have to wait until 1886.

At the time of their marriage Margaret's family name was Davidson but as she was probably widowed this may not have been her maiden name. There is no identifiable record of a matching marriage and death as 'Davidson' is very common in both England and Scotland. A future researcher may need to wait for DNA analysis to catch up before we can work that out.

Either Margaret brought some capital to the marriage or William worked very hard or cleverly. After a couple of years in Gateshead they moved across the river to the parish of All Saints in Newcastle and set up a factory to manufacture lemonade. This was between the birth of Alexander and James - in 1834-35.

Lemonade is frequently mentioned in accounts of the time but there are few earlier references to the manufacturers.

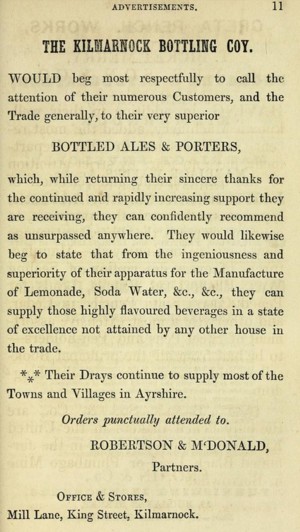

Possibly Margaret had associations with lemonade and soda water manufacturing in Ayr? The first commercial manufacture of Soda Water using the Priestly process was Thwaites' Soda Water in Dublin, established 30 years earlier. The close association between south-west Scotland and Ireland meant there may have been a firm there already trading in soda water and lemonade.

There certainly was one 15 years later that may have preceded the one they set up in Newcastle:

The Ayrshire Directory (1851) |

|

|

Newcastle upon Tyne was an ideal location for this business. At that time, it was close to being the wealthiest city in the country and the centre of the northern glass industry for bottle making.

A contemporary commentator sang of the town's virtues (the language is marvellous - quite unlike that a century later):

Richardson's descriptive Companion through Newcastle upon Tyne

|

|

CHAPTER XV. PERAMBULATIONS THROUGH THE TOWN, AND GENERAL NOTICE OF THE STREETS. GEOGRAPHICALLY and relatively observed, the mere seat of Newcastle on the map of the world fixes on it high distinction, cut out as it has been by nature for a secure and spacious shipping resort. It stands in 54deg. 58min. 30sec. north lat.; and 1deg. 37min. 30sec. west longitude, from the meridian of Greenwich, being 273 miles NN.W. of London; 117 SE of Edinburgh; 56 east of Carlisle; 76 NW. by N. of York, and 15 north of Durham.

|

During the 1830's there were regular outbreaks of cholera in Newcastle, as in the rest of England, and indeed in Sydney Australia. Few people could afford town water piped into their homes. Fountain (public) water varied in quality. At the very least it needed to be boiled before drinking. Safer drinking alternatives were beer, ginger beer, soda water and/or lemonade. As a result, lemonade was sold in large volumes as a non-alcoholic alternative to beer and was favoured by religious sects that frowned on intoxicating beverages. It seems likely that both William and Margaret were Presbyterians, doing God's work.

Tea of course had long been used to flavour boiled water but at that time it was still very expensive worth its weight in gold, and the china used to serve it was also a mark of wealth. The middle classes, including members of my family, met in tea shops to enjoy it and invariably offered it to special guests in their homes, a tradition now but a mark of social status then. Not until the advent of steam ships and railways did the cost of tea fall to today's relative prices. In Boston in 1773 destroying tea had marked the beginning of a revolution.

To manufacture lemonade a source of lemons was the least of their concerns. First and foremost, William and Margaret McKie required a reliable source of water; bottles and casks to contain their product; boiling and pressure vessels; and fuel, gas or coal, to run their equipment.

Obviously, there was no electricity distribution in 1835 but Newcastle had coal of course, and now gas was becoming available:

Richardson's descriptive Companion through Newcastle upon Tyne

|

|

CHAPTER XIV. MISCELLANEOUS ESTABLISHMENTS FOR THE ACCOMMODATION OF THE PUBLIC. GAS WORKS The first gasholders were built in Forth-street, in 1817, from which, on the 10th of January 1818, a partial lighting of the town with gas commenced. The same company afterwards erected works in Manor-place, where there are two other holders, and in 1833, and 1837, the company erected two other similar holders at the North-shore, the whole of which are capable of containing nearly 200,000 cubic feet of gas, the quantity frequently consumed in the town on a Saturday night.

|

The business was obviously doing well in the late 1830's and early 1840's and it was time for a move to larger premises.

They found appropriate factory space with accommodation adjacent to expand their lemonade factory in Dispensary Square, adjacent to Blackfriars. This was around 1845, give or take a year or two.

There was reliable water, possibly of dubious quality, and other water using industry, including a slaughterhouse, nearby. This water would certainly have required industrial scale boiling and clarification with a suitable flocculent and filter.

Perhaps I have acquired some residual memory, through my father, about sand filters, activated charcoal and diatomaceous earth, how else would a desk-bound public servant know about such things?

But my father had a vast and varied knowledge about lots of things. It was not necessarily handed down from his father. For example, my brother, Peter McKie, has had reason to clarify huge tanks of water for television commercials and the film industry. His intellectual ability to do this may be in his genes but I imagine that he had the help of a technical manual or two as well. Lamarck eat your heart out.

Richardson's descriptive Companion through Newcastle upon Tyne

|

|

CHAPTER XIV. MISCELLANEOUS ESTABLISHMENTS FOR THE ACCOMMODATION OF THE PUBLIC. WATER WORKS. ...Water still being insufficiently supplied, the corporation in 1770, granted a lease for 227 years to Mr. Ralph Lodge and other proprietors at the annual rent of 13s. 4d., to dig and make a reservoir at the south end of the town moor, and to lay pipes for bringing water to it from Coxlodge grounds, and from the reservoir into the town; also, for supplying water for a certain number of fire-plugs ordered by the corporation. In 1777, the common council expended £500. in aqueducts for conveying an additional quantity of water to the town from Spring Gardens; and for more than half a century the management of the supply, which was derived partly from this last source, partly from the reservoirs on the town moor, with others at Gateshead, and the great pond at Carr’s Hill, was vested in a Joint Stock Company. At length, in 1833, a project was set on foot by a new company for again having recourse to the river, from which it was proposed to afford the necessary supply on less expensive terms; but soon after the new plan had been brought into operation by forming reservoirs and erecting an engine at Low Elswick, which is allowed to be a piece of the most perfect machinery in the kingdom, the two companies became incorporated, and the supply has been since continued under certain new regulations, from the various sources Thus, successively opened.

|

By the time of the 1851 census Elizabeth had left home and was probably married, possibly as Elizabeth Davidson.

The McKies were now providing accommodation to Robert Courage a Tallow Chandler.

A Tallow Chandler made tallow candles that were used for lighting by the majority of people who could not afford wax candles or that newfangled gas lighting. The tallow was produced by rendering animal fat from slaughterhouses, presumably the one in Dispensary Lane. Tallow candles were sold by the pound. The process was very smelly and, like those scented things sold in tourist and gift shops today, the candles were particularly smelly when burnt - like a barbeque - pleasant if you like the smell of burnt meat fat. As a result, they would soon be replaced by gas lighting, except in the homes of the very poor. Thus, technological change would soon make Robert Courage, and his fellow tallow chandlers, redundant.

It's as well William, Margaret and Jane moved across the river, because in 1854 much of the industrial part of Gateshead was consumed by the Great Fire.

The port was at that time at the centre of the wool trade and the fire began in an old wool store but spread to a substantial modern store holding chemicals, including 2800 tons of sulphur and 128 tons of nitrate of soda.

These were the chemicals Peter and I used as children, trying to make our own explosives. See my recollections elsewhere on this site ( Making Gunpowder). But as we discovered, sodium nitrate is hydrophilic and not much use for making gunpowder.

Nevertheless, it obviously dried out as the fire took hold in the sulphur. There were a couple of small warning explosions, as the fire grew, followed by an almighty explosion, never equalled since, even by the Luftwaffe, that was heard over 40 miles away and showered Newcastle across the river in heavy stones and timber beams. It left a huge crater 40 feet deep and 50 feet across. A fire-storm followed that devastated much of Gateshead.

This hand-coloured woodblock engraving from the Illustrated London News, 14 October 1854

also serves to show what the city looked like at the time - just before photography was invented.

Science and Technology

Technological change was rapid in this period. Soon they were making soda water. The McKie lemonade business required new machines and knowledge. In addition to a good supply of potable water, water filtration and heating required a knowledge of chemistry and biology for water purification and blending syrups and added salts and sugars.

Carbon dioxide, required to put the bubbles in soda water, could not be extracted in large volumes from air or made as a by-product of fertiliser manufacture as it is today.

It's always been a natural by-product of beer and wine making and puts the little bubbles in cakes and bread. It could be pressurised with a suitable pump from the head space above wine or beer fermentation but entrapped nitrogen would limit its compression or it could be manufactured in a pressure vessel using the method suggested by Joseph Priestley and used in Dublin: by applying strong acid (sulphuric was most available) to chalk or crushed limestone.

Over the next century these processes would change dramatically. Compressors would be built that could compress CO2 produced by calcining lime [CaCO3→ CaO + CO2] and later to cool air to the point that dry ice (solid CO2) forms.

There was no shortage of modern scientific knowledge in Newcastle.

From 1793 the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle (the Lit and Phil) had been a hub of scientific discussion in the north of England. In 1825 the current building that houses it was completed, providing meeting rooms and a library.

At the time the McKies were establishing their business Newcastle was abuzz with the new discoveries. The first platypus seen in England was sent not to London but to Newcastle. John Hunter, governor of NSW Australia, was a member of the Lit and Phil and had one sent to the members for their consternation and consideration.

As I imagine everyone knows, a platypus is an amphibious mammal that lays eggs and has a duck bill, one of the few remaining monotremes on earth. As my great great great grandparents were setting up their factory Charles Darwin was in Sydney Town grappling with one in a local creek and discovering the poisonous spur on the hind legs of the male.

Soon the discoveries of Lyle and Darwin and Wallace would overthrow many old scientific paradigms in addition to making nonsense of religious dogma.

The platypus would soon demonstrate that mammalian ancestry dates from a relatively recent hundred million years or so and a little further back they have a common ancestor with the McKie family - well, with your family too. But it would take until my generation to discover that the Universe is breathtakingly larger than anyone then dared to imagine and is now thought to be 13.8 billion years old.

The Lit and Phil had close associations with similar societies across Britain and Europe, particularly France. In 1834 Benoît Clapeyron stated the Ideal Gas equation and in 1857 Carl Wilhelm Siemens would patent the Siemens cycle, cooling gasses by repeated compression heat removal and decompression as used in most refrigerators and air conditioners today.

As Richardson notes, the population of Newcastle was growing rapidly, passing 53,000 in 1831, and the Centre of the city was under reconstruction, the origin of the many fine buildings we see today around Gray's monument as evidence of its wealth. For the first time a police force had been formed, charged with keeping the new streets safe. Gas lamps were already being used as street lights in parts of the city, these would soon be replaced by advanced gas lamps using a mantle to provide brilliant white light.

As Newcastle expanded in the 1850's new suburbs spread out beyond the city walls and town moor. Science, technology and engineering dominated the thriving city.

In 1835, when William and Margaret McKie were founding their lemonade manufacturing business, Newcastle was giving birth to the industry that would dominate the next century - the passenger railway.

Less than a mile from McKie's lemonade factory, in Forth Street, George Stephenson and his son Robert were at work.

A decade earlier Robert Stephenson and Company had been established by the Stephensons to manufacture locomotives for the Stockton and Darlington Railway.

Soon the world's first passenger railways were spreading out around Newcastle like roots from a bulb. Part way to Carlisle in 1838, then to Darlington in 1844 and to Berwick in 1847. No doubt some workers at the factory, and then passengers on the trains, were washing away the dust with a McKie lemonade.

Might Newcastle's 'golden period' have been a result of 'something in the water'?

Around the world huge fortunes would soon be made by 'railway barons', more often through associated land development and constructing new towns in the Americas and the Empire, than by the fares charged to travel. With railways came the electric telegraph and the first opening-up of communications.

Now even time changed. It had to be unified where the trains ran, instead of being set locally, by the midday sun, in each town. Greenwich Mean Time or 'railway time' as it was called, was adopted across Britain in 1847-8. And one hour 'Time Zones' soon divided the entire planet, giving us an International Date Line.

George Stephenson had developed the first successful miner's safety lamp and the first practical steam locomotives for passenger trains, based on the experience gained around the city moving coal, first with steam run mine elevators and cable cars and then with self-powered locomotives.

He is, justifiably, called the 'Father of Railways'. He was very rough around the edges and plain speaking and was not liked in London.

As a younger man he had been an engineman at Killingworth Colliery, responsible for all the machinery: pumps; lift engines and so on. The mine was subject to repeated explosions due to 'firedamp' and in 1814 responsibility fell to him deal with yet another explosion and fire, resulting from a naked flame. So he began experimenting with designs for a mine safety lamp using local sources of 'fire damp' directly to test his designs.

Meanwhile the problem had attracted Sir Humphry Davy, the aristocratic scientist whose achievements are too long to list here but included isolating the elements: Barium; Calcium; Potassium; Sodium and Boron; and identifying Chlorine as an element. Davy was also at first the employer and then the mentor of physicist and electrical pioneer Michael Faraday and was later President of the Royal Society. He was famed for his scientific demonstrations to the upper classes and he was responsible for a ground-breaking electrical demonstration discussed later.

Davy approached the problem scientifically, first analysing 'fire damp' to discover that it was mostly methane and then devising a screen sufficiently fine to prevent a flame passing through it. The resulting Davy Lamp won prizes totalling £3,000. But Stevenson had already demonstrated his, practically superior, lamp at the Lit and Phil in Newcastle. When this was pointed out the colliery owners, who had already recognised Davy with £2,000, awarded a measly one hundred guineas (a guinea is £1/1/-) to Stephenson in consolation. The people of Newcastle were outraged at this insult. A local committee raised £1,000 by subscription and awarded it to Stephenson.

Stephenson called his miner's lamp the 'Geordie' after the Newcastle patriots who had defended the city during the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745 on behalf of George II and were despised as 'Geordies' in a popular song supporting the rebellion. Probably thanks to him, the name was soon attached to the people of Newcastle and the Tyne Valley in general.

It was that local prize that allowed Stephenson to go on to his greatest achievements.

The incident also helped to reinforce the Newcastle culture of independence and suspicion of those from the South. This still existed as recently as the late 1970's, when my grandmother's elderly neighbours proudly announced that they had been to Spain but had never been south of York in the UK. How did we survive in that dangerous den of iniquity: London?

George's son Robert Stephenson, on the other hand had no such prejudice. He was well educated, in leading schools and university, and was quite at home in society. Together the Stephensons combined modern scientific and engineering knowledge and a wealth of practical experience as well as business acumen and political nous.

Stephenson's Innovative 'Rocket' - designed in 1829 for the Liverpool & Manchester Railway

This was the prototype for locomotives to come with: large driving wheels, directly connected to (nearly) horizontal cylinders;

a separate firebox with multiple boiler fire-tubes, and a blastpipe to draw the fire.

It could not be a lot bigger/heavier or it would have broken the old iron rails of the day. Science Museum, London (my photo)

By 1847 the practice of pulling goods trains by steam and passenger trains by horse had pretty well disappeared but there was still some nostalgia for the horse, as this little piece shows. No prizes for guessing how I came to see it.

Carlisle Patriot 24 September 1847 |

|

|

In 1847 Robert Stevenson designed and supervised the construction of the innovative High Level Bridge across the Tyne that is still in use today. It is a truly remarkable achievement, exploiting the most advanced technology of the day. Wendy and I recently travelled over it on our way from London to Edinburgh.

The High Level Rail Bridge Newcastle to Gateshead with the Swing Bridge in the foreground (my photo)

It was but one of half a dozen equally innovative bridges he would design. He was personally responsible for dozens of railways across the world with ever improving locomotives. He was one of the people, who through his inventiveness and industry, put the 'Great' before Britain. He is buried in Westminster Abby.

In Australia, the first locomotive on the Sydney to Parramatta railway was built by the Stephensons in Newcastle upon Tyne.

Locomotive No1, built by Stephenson & Company for the Sydney to Parramatta Railway

manufactured less than a mile from William and Margaret McKie's lemonade factory

The little girl in the foreground is their great great great great granddaughter, Emily (my photo)

The Stephensons weren't alone, another locally born engineer George William Armstrong had taken an interest in hydraulics, designing innovative cranes. He set up a manufacturing facility on the banks of the Tyne at Elswick in 1847. The business was very successful, contributing significantly to the town's population growth. By 1870 the company premises stretched for three-quarters of a mile along the riverside.

It's nice to think of them all drinking McKie lemonade as they worked on their drawings, like today's computer nerds and their soft-drink.

Armstrong designed the first modern, rifled, breech loading, field gun. This was used around the world and by both sides in the American Civil War and soon adopted by the Navy, initially for long range targets.

Remember that up until then warships were still wooden sailing vessels with a gun-deck and muzzle loading cannon to deliver broadsides.

USS Constitution - still the flagship of the US Navy

One of the most powerful warships afloat in 1816

She thrashed several British ships in the War of 1812 (my photo)

Soon the first ironclad wooden ships would replace these, followed by all-steel, steam driven battleships with gun turrets.

To fit their guns warships needed to navigate up the Tyne and the old multi-arch masonry 'new bridge' (that you can see in the early woodblock picture above) was in the way. So in 1876 Armstrong’s company paid for its demolition and the new Swing Bridge that you can see in the photograph above to be built, allowing their passage.

In the 1880 Armstrong's Elswick works would begin building the new style of warship from the keel up. They soon became the most innovative heavy engineering business in the world. It was they who built and installed the steam-driven pumping engines, hydraulic accumulators and hydraulic pumping engines to operate London’s Tower Bridge. Armstrong was knighted in 1859 after giving his gun patents to the government. In 1887, in Queen Victoria's golden jubilee year, he was raised to the peerage as Baron Armstrong of Cragside.

Both steam-power and shipbuilding were to play an important part later in the McKie saga but for the moment the family was focussed on soft-drink production.

The railways also heralded significant developments in the iron industry. Early trains had to be small and relatively light like the Rocket or they broke the brittle cast iron rails. In 1820 another local man, John Birkinshaw, had gained a patent for rolling wrought-iron rails. The Stephensons immediately saw the potential and took him in as partner. Wrought-iron was a much more malleable and less brittle material than cast iron and the industry scaled up production, facilitating the manufacture of rails that did not break so that locomotives, wagons and carriages could grow to their now familiar size.

In June 1842 the new railways were endorsed and adopted by royalty

when Queen Victoria was 'charmed' by her first experience of train travel

The invention of rolled wrought-iron in Newcastle made the railways possible and soon facilitated the construction of innovative new bridges and ships and the first skyscraper buildings and what would be mankind's tallest structure: the Eiffel Tower in 1889.

By the 1850's puddling furnaces, already used to make thousands of tons of wrought iron, were evolving, using regenerative reheating, (the Siemens-Martin process) into open hearth furnaces and Bessemer was trialling his bottom-blown iron conversion furnace, using air, in Sheffield, 130 miles to the South. The new product was steel. The Bessemer process was faster and cheaper but suffered from nitrogen embrittlement, a problem not fully resolved until the mid-20th century when tonnage oxygen plants became available.

Steel that once took a skilled blacksmith days to make in small quantities, by repeatedly folding wrought iron, could now be made in thousands of tons in a matter of hours, revolutionising engineering. It was a new 'miracle material' - increasingly alloyed to other metals like: manganese; nickel; chromium; lead; and copper. These new materials would change the fortunes of the McKie family for generations.

In the next century and a half this new steel industry would provide the means of making electricity, building ships, and constructing modern guns and bombs and aircraft. Great fortunes would be made. Steel technology would revolutionise everything, including the kitchen sink, helping mankind to reach the Moon, and provide a career opportunity to at least one McKie descendent. Enormous iron ore and metallurgical coal exports would help to keep Australia 'the lucky country'.

All this had its genesis in the endeavours of those few men, with the support of their wives and daughters, who thrived in Newcastle upon Tyne in the mid-19th century.

A soda water bottle marked Jas. McKie and Son

The next generation arrives

By 1847 William McKie was taking an active interest in the life of the community. He was a member of the expatriate Scottish Diaspora in Newcastle and his sons followed in his footsteps, despite being first generation Englishmen. We have to imagine him bearded in the garb of the day: a long black frockcoat and top hat, perhaps with a silver-headed cane.

William and several associates on the committee of management took out advertisements in several newspapers in support of arrangements for the Close Schools. It suggests rather strong religious prejudices:

Newcastle Courant 28 May 1847

|

|

|

In to this upright environment a new McKie unexpectedly arrived in 1849, after a 13-year gap, when Margaret was 53. Their daughter Jane, now 17, had become a dressmaker, a profession, and a name, that is commonplace among my ancestors on both sides of my family. In the following census little George was listed as their son.

But ten years later neither Jane nor George still lived with them and I can find no further convincing record of either. Perhaps they emigrated.

The two older boys Alexander and James were now young men about town. Alex McKie met a good Scottish (he would have said Scotch) girl Mary Watt. They were both 18 when they married in 1852. Maybe she lost a baby or two because there is no child for some time but they eventually had three girls and a boy (Margaret, 1856; George William, 1859; Annie, 1865; Janet, 1867).

James, my great great grandfather, would soon follow his brother's lead. James had met a local girl, Elizabeth Lawson, and married her in 1857 when they were both 21 years old. The boys may have met their future wives at their Scots Church (Presbyterian) where they were Baptised. Church was the great nineteenth century meeting and mating place.

Elizabeth was the daughter of James and Frances Lawson (nee Dowse). They lived in nearby Orchard St in the same Parish (St John).

Meanwhile, William or Alexander or James (its not clear which) were sorting out the problems of being an employer and the foibles of mankind, confounded by that dreadful curse: alcohol.

Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury 26 November 1859 |

|

|

Elizabeth and James' first child James (Junior), my great grandfather, was born in 1859; followed by Margaret Jane, 1860; Frances Ann, 1861; Elizabeth, 1863; Mary, 1865; and my great uncle, Jacob Lawson McKie, 1870. Jacob is important later in our story.

In December 2017 David Hopper, Frances McKie's great grandson contacted me. David's provided the following information:

|

Below is a photograph of Frances 1861-1909. She married a John Reid and she had 2 sons: Stanley & Lionel. Stanley was my grandfather. His brother Lionel left home and went work in the Russian oilfields as a secretary. He was an early member of the SIS working in Russia during WW1 and the revolution. He was awarded a military OBE in Vladivostok in 1917. The SIS later became MI6 which he worked for mainly in the Eastern Bloc until his death in 1953. Frances was deaf later in life and she had a very unhappy marriage until her untimely death in 1909, possibly suicide? |

|

|

This stimulated me to get to the bottom of this, to me at least, confusing 'cousin' thing:

Family RelationshipsCousin First Cousin, Full Cousin *Guidance provided by Jennifer Crichton's 'Family Reunion' |

Thus, David is my second cousin. He's also second cousin to my brother Peter, as well as to our first cousins: Shelia; Pamela; Patricia; and Jane.

Back to the story:

Both Alex and James now took active roles in the business and both declared themselves proprietors in the 1861 census, when it was still located at Dispensary Lane.

Now the lemonade business could be called McKie & Sons.

As the city grew so the McKie lemonade manufacturing enterprise also grew. New products were developed, like ginger beer, and the business was renamed a soda water factory. But the original location was less than ideal. It was time for a move to a more salubrious location.

A hundred years later the whole Dispensary Lane and Square area would be condemned as a slum.

A century later - a slum

The buildings they occupied there have since been demolished and rebuilt as up-market dwellings. Dispensary Lane's most recent claim to fame was a rape - perpetrated by a 'painted man' - a rapist wearing makeup.

With the new Water Corporation came the first public baths, a grand building constructed out in what was then the semi-rural Parish of St John, serviced by a newly constructed Bath Road off Northumberland Street.

Richardson's descriptive Companion through Newcastle upon Tyne

|

|

CHAPTER XIV. MISCELLANEOUS ESTABLISHMENTS FOR THE ACCOMMODATION OF THE PUBLIC. PUBLIC BATHS After a number of meetings for the purpose of deciding upon the best plans and arrangements, it was finally determined, at a meeting of the shareholders and others, held on Tuesday, August, 27th., 1837, to immediately proceed to erect the public baths* according to designs submitted by J. Dobson, Esq., architect, who had visited most establishments of the kind in England, for the purpose, if possible, of improving upon their construction. *Upon the corporation granting this contract, the committee invited the skill of the town and neighbourhood in order to determine, by analysis, the most wholesome water that could be obtained for the supply of the town and the result of the tests proved the purity of the Coxlodge springs, which was confirmed by professor Black of Edinburgh, and Dr Saunders, an eminent chemist of London.

|

|

|

What better new location could there be for a soda water factory than adjacent to the Coxlodge springs, recently endorsed by professor Black of Edinburgh, and Dr Saunders? And so 400 yards down Bath Road from the new baths, west towards Northumberland Street, land was acquired and William McKie and his sons, Alexander and James, set up the McKie and Sons Soda Water Factory, with new, finer, accommodation for the family.

The year Jacob was born there was a little drama in Carliol Street when Mr Turnbull's horse ran amok.

Newcastle Courant 12 August 1870 |

|

|

A swinging boat was a kind of two-person swing, popular in the north-east of England at the time (a shuggy boat), where a couple would sit at either end and pull on ropes to swing the 'boat' higher until the ends were swinging above the fulcrum, the origin of the word 'skylarking'. The modern fairground equivalent is a swinging 'Pirate Ship'. Why there were several in Carliol Street near the gaol in 1870 is a mystery that Google Street View fails to shed any light on.

So, a couple skylarking scared a horse that ran amok and generated a media report. As a result of this unlikely set of circumstances they inadvertently left a message for generations to follow, confirming that the McKies had moved to Bath Road before August 1870; that the McKie sons were in the process of taking over the reins from their father; that they no longer called themselves lemonade manufacturers; and that they had previously owned at least one horse.

Collage of maps of Newcastle upon Tyne

|

|

|

By the time of the 1871 census William and Margaret had taken a step into semi-retirement, with the assistance of a Scottish servant named Janet Hair.

In 1874 the business was news across the region. This was one occasion when the adage: 'there's no such thing as bad publicity' was true: An employee, Ellen Barrett, fell into the River Tyne while out for the night with her boyfriend.

Her young man Robert Marr was arraigned for her murder.

He had bought her a shawl earlier in the evening and perhaps wanted a favour in return and after the public houses closed, they made their way to the quayside and sought the privacy provided by a 20 ton crane. Several other young people were also in the area and heard them quarrel. She wanted to 'come away'.

Then they saw Robert running off. So, they looked for Ellen, in vain. Two days later her body was found on the other side of the river in a decomposed state.

Did Ellen fall or was she pushed?

Morpeth Herald 30 May 1874

|

|

|

Ellen had friends who also worked at the factory who were very distressed. Her large funeral cortège was routed past the McKie Soda Water factory.

Robert Marr was eventually convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to penal servitude for a period of 12 years. He left the dock protesting his innocence, as well he may have been as the evidence was circumstantial. But he was never going to walk free. If it had been an accident, he hadn't attempted to save her. He hadn't even given the alarm but ran away. He probably couldn't swim and panicked but he'd pay for that.

At around the same time in 1875 Alexander McKie too had died at the age of 41. He left his wife Mary McKie a widow with four children, aged 8 to 19. The business name was back to McKie and Son, singular.

If Alex's death wasn't bad enough at the age of 19, James McKie Junior, James' son, impregnated Mary Ann Ritchie who was also 18 or 19. They were married in the second quarter of 1878 and around three months later their first child Mary Ann McKie (junior) was born.

Were they forced to marry or where they in love?

Although premarital sex was a common occurrence, it was considered very lower class and not the norm or to be hushed-up in respectable middle-class society. This was particularly the case in our family where the patriarch had spent his life bettering himself from an itinerant labourer to become a respected businessman and a pillar of the Presbyterian Church. The timing of this birth was something they wanted to cover-up so they lied about the baby's age in the 1881 census.

All this seems ridiculous today, when none of their descendants would marry someone they hadn't lived with first or who they considered to be a suitable potential life partner. But then it's unlikely they would give birth to an unwanted child either.

Had the family been comfortably a bit higher up the social ladder or less enthusiastically religious the pregnancy might have been handled differently. Mary Ann herself may have been surprised at being obliged to marry. She was the daughter of Ann Ritchie or possibly Isabella her sister, neither of whom was married. Ann and Isabella were the daughters of Robert and Mary Ritchie and they both worked as servants.

It seems that there was retribution. James McKie Junior was expelled from the family home in Bath Road. My great grandfather's family initially moved to 12 &14 Thorpe Street, since demolished and now what looks like public housing in Google Street View. Then they moved to 65 Meldon Terrace Heaton and this is where my grandfather spent his childhood. You can still see this modest terrace-house on Street View.

On August 20 1879 one James McKie, of Bath Road, Newcastle-on-Tyne, soda water manufacturer, was declared bankrupt.

Western Daily Press 20 August 1879 (and others) |

|

|

But two years later James McKie and Sons, Soda Water Manufacturing, remained a going concern in Bath Road, employing 15 Men, 4 Boys and 4 Women. So we can conclude that either there was a temporary problem in the business or it was James Junior who was unable to satisfy his creditors in 1879.

It seems that it was James Junior who was unable to call on the family assets as he had been cut off and was now out of the succession.

Old William McKie the patriarch died a year later 1880 at the age of 77, possibly exacerbated by the scandal, and it's probable that he was responsible for young James's financial plight or possibly for a reversal of the bankruptcy. Margaret outlived him by four years and died at the very old age at the time of 87.

The stigma of the marriage seems to have been more about hushing-up my great grandmother's background than about a child arriving early. Although she contributed a sixteenth of my DNA, I had never even been told what my great grandmother's maiden name was - I always assumed it was Lawson. I did know that there was a family scandal about an unplanned pregnancy involving a maid. But that was as much as I was ever told. Through a process of elimination, delving into the records, I now discover that my great grandmother was Mary Ann Ritchie.

Her anonymous father is one of the three of my sixteen great great grandparents who remain unknown to me, it's interesting that all the known men had a skilled trade or were in business. Presumably my great grandmother's father was her mother's employer or an associate of her employer. Maybe he was someone academically brilliant? There were a lot of candidates in Newcastle back then.

Mary Ann's unmarried mother was one of my great great grandmothers. Her father, my great great great grandfather, was Robert Ritchie, a joiner from Gateshead. His wife was Mary but it's not possible to identify their parents. Like McKie, the Ritchie family name has origins in Scotland and Ireland. At the turn of the century the name distribution was similar to McKie but they are far more numerous.

James McKie (senior) was now in full control of the business as can be seen in the early photograph below. But it is now Jacob McKie who will succeed.

James McKie and Sons in 1898 - in Bath Road (now Northumberland Road). Northumberland Street is in the distance.

The Public Baths are on the same side, a block behind the camera.

The side street, Ridley Place, is now John Dobson St, the major crossroad in the 2010 image above.

Note the gas street lights. This type employed the newly introduced gas mantle, producing a brilliant white light.

These were leading edge technology and delayed the introduction of electric lighting in locations like this and in Sydney.

Around the time of the 1898 photograph Bath Road was renamed, rather confusingly, to 'Northumberland Road' and the baths became the Northumberland Road Baths.

As the colour photograph from 2010 shows, the baths are still there today, but I doubt that gentlemen of the upper class still have an exclusive section.

Ginger Beer bottle marked Jas. McKie and Son Northumberland Road

What happened to 'Sons' ?

Note that we now have a telephone

Mary Ann McKie bore James McKie Junior five children: Mary Ann McKie (junior) in 1878; James William Lawson McKie, my grandfather, in 1881; Margaret a year later; then Thomas another year later; and finally, Laura in 1887.

Then some time after Laura was born, Mary Ann McKie (the elder), my great grandmother, completely disappears from the records. She was no longer a member the household of James McKie Junior in the census of 1891.

I have been unable to find a death notice for her anywhere in England. But there was a married woman called Mary Ann McKie, in a single berth, leaving for New Zealand in 1908. There was also a press article in the Northern Echo of 6 November 1900 about the wife of one J McKie, who may or may not be related, who was sewing for maintenance on the grounds of desertion.

By 1891 James' sister, Margaret Jane McKie, had moved in at 65 Meldon Terrace and they now had a live-in servant too: Mary Heywood (aged 18).

There must be a lot of drama at home when my grandfather had his mother either leave, or perhaps die, at the age of 9 or 10 and he acquired his aunt in her place.

In September 1897 James McKie (senior) died leaving Jacob McKie in control of the water business.

Hartlepool Mail 30 September 1897 |

|

|

Notice the business name is 'McKie and Son', singular.

Then in 1905 Margaret Jane died at the age of 41. Five years later in 1910, James Junior was dead too at the age of 51. I don't know the cause. But my father talked darkly of alcoholism in the family, warning Peter and me not to over-indulge. Given his circumstances he may have simply given up. All the McKie men were dying young, except old William who lived to the age of 77. As we will see, at least one death was a suspected 'felo de se'.

Both of James' and Mary Ann's boys: my grandfather, JWL, and Thomas McKie had left home soon after their aunt died.

My grandfather's unmarried sisters Mary Ann (31) and Laura (23), now parentless, moved in with their uncle, Jacob McKie, at Number 1 Northumberland Road. Jacob was now the inheritor of the McKie Water business together with their aunts Elizabeth and Mary. In the census Laura is listed as a typist in the business.

They and my ancestor had parted ways.

The Scientific Revolution

The Telephone

In the 1870's those new telephone fandangles were expensive and not a lot of use if no one else you knew had one.

The McKie water business was an early adopter, no doubt to accommodate wealthy customers. The first telephone was invented by the Scotsman, Alexander Graham Bell. It had restricted range and required shouting into a variety of not very practical microphones, some even using pools of mercury, to convert sound to an electrical signal.

Most microphones, particularly those in phones today, that are based on electret materials, require some kind of electrical amplifier to convert sound waves bouncing off a diaphragm into a useful electrical signal. This was a major handicap prior to the invention of thermionic valves or transistors. What was required was a microphone that would be its own amplifier. Three men had a similar idea: using a small container of granulated carbon as a variable resistor, arranged so that it would change its resistance to current when compressed and decompressed by a diaphragm moving to soundwaves, like the eardrum and associated components in your ear.

A patent dispute followed in the US, with Emile Berliner, the inventor of the modern Phonograph (with records we would recognise) claiming priority. This was resolved when the patent for the granular carbon microphone was eventually granted to Thomas Alva Edison in 1877.

The Bell Telephone Company quickly acquired the Edison patent in 1879. Suddenly Bell Telephones could make calls the length of England, or even more impressively, trans-continentally across the United States or Australia or Russia.

Edison's invention was of incredible importance. So, it is this for which he should be most remembered, not the light bulb or the phonograph. The carbon microphone is an unsung but pivotal invention of the late nineteenth century. It was still in use in every telephone handset and telephone box in the world until well into the second half of the 20th century. I've still got one in a box somewhere.

The carbon microphone was not fully replaced until the 1980's when smaller microphones requiring semiconductor amplification could be used, mostly after electronics had been incorporated into handsets to facilitate tone-dialling. It was also the basis of the first hearing aids.

The carbon microphone allowed the first public address (PA) systems to be built, advancing a new type of political demagogue at mass political rallies.

Perhaps equally importantly, the first singers who had not been trained project their voice, could heard throughout a large theatre, setting the stage for radio, movies TV and electronic communications. Imagine a world without microphones.

The electric light bulb

Edison is often credited with the invention of the electric light bulb too - or simply 'electric light'. But this is not so.

At the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society new things were afoot. On 3rd February, 1879 Sir Joseph Wilson Swan, demonstrated his Incandescent Electric Lamp to an audience of over seven hundred people. Then on the 20th October, 1880, during a lecture, Swan gave the signal for all the seventy gas jets to be extinguished and switched on twenty of his own lamps, which ‘amazed the audience with its suddenness.’

Thus, in 1879 the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society’s lecture theatre had been the first public room in the world to be lit by electric light bulbs.

This event was to change my family's future and the entire World forever.

Eleven months later, on December 31, 1879, in Menlo Park in the US Edison would make his first public demonstration of an incandescent light bulb. It was said that he had developed the idea entirely independently. Who knows, he was a great borrower and improver. His US patent was applied for a full year after Swan's was granted in England.

But neither had 'invented' electric light.

Sir Humphrey Davy, George Stephenson's nemesis, had invented the electric arc lamp in the early 1800s. Electric arc lamps were already replacing gas limelight, used in live theatres, and are still used for some theatrical purposes. They were used in cinema projectors until the 1990's as well as military searchlights and lighthouses and provided the first practical electric light.

As a boy I helped make a little one with a tinplate can as the reflector, using Meccano and pencil leads for electrodes. My father oversaw the project to ensure I didn't blind or electrocute myself. A carbon arc can be exceedingly bright but the lamps continuously consume carbon electrodes and generate a lot of heat.

In 1800's they required a large bank of batteries and/or a dedicated dynamo and they are not suitable for continuous use for more than a few hours.

It's difficult for us to recapture the marvel of bright electric light. The public was enthralled. Crowds would gather for public demonstrations of lighting. Searchlights can still impress and are sometimes used for movie openings.

For example as early as July 1880, Lt. Col Cracknell, Superintendent of Telegraphs for NSW (Australia), publicly lit one of the caverns at Jenolan Cave’s with electric light using arc lamps. A small dam was then built and a turbo generator, using an American Leffel wheel, was installed to light the caves, in one of the first public electric light installations in the World. You can still see the original plumbing as well as the more modern replacement turbines along the river walk below the dam. The caves of course are spectacular and much loved by the McKies in Australia. People travelled from England, when it took months, just to see them.

|

|

Jenolan Caves Electrification - 1889 (my photos)

But arc lamps were poorly matched to domestic lighting. Not only do they consume the electrodes but they also produce ozone that smells and may be harmful; considerable heat; and dangerous ultraviolet radiation. The challenge was to produce an affordable long-lasting pollution free electric lamp suitable for continuous domestic use, that was at least as bright and reliable as a contemporary gas mantel.

Gas mantles are still used in the gas lamps people take camping. They produce a dimmable bright white light that can be the equivalent of an incandescent bulb of several hundred Watts.

Twin mantle gas lamps - still in daily use at Westminster Abbey - very bright

Twin mantle gas lamps - still in daily use at Westminster Abbey - very bright

Almost every house I've lived in as an adult, including this one, was once lit by gas mantles and I've pulled out the remnants of old gas pipes from three of them.

Edison realised that if an electric bulb could be developed, electricity from his direct current (DC) dynamos could be reticulated through cables and sold to a mass market to compete with gas.

He was in the process of developing perhaps the World's first commercial research laboratories. This complex, over two blocks in West Orange, New Jersey, included chemistry, physics, and metallurgy laboratories; a machine shop; a pattern shop; a research library; and rooms for experiments. It came to be known as the 'Invention Factory' with dozens, and later, hundreds, of engineers and scientists developing patentable ideas. Edison realised the bankable importance of his reputation as the world's greatest inventor. Thus, the inventions and developments generated by his labs were almost always attributed to him personally.

In this he had the financial backing of J. P. Morgan and the members of the Vanderbilt family, in addition to many smaller investors. Whereas Swan was a scientist, for whom invention was a by-product of his curiosity and experimentation, largely backed by his own resources and interests.

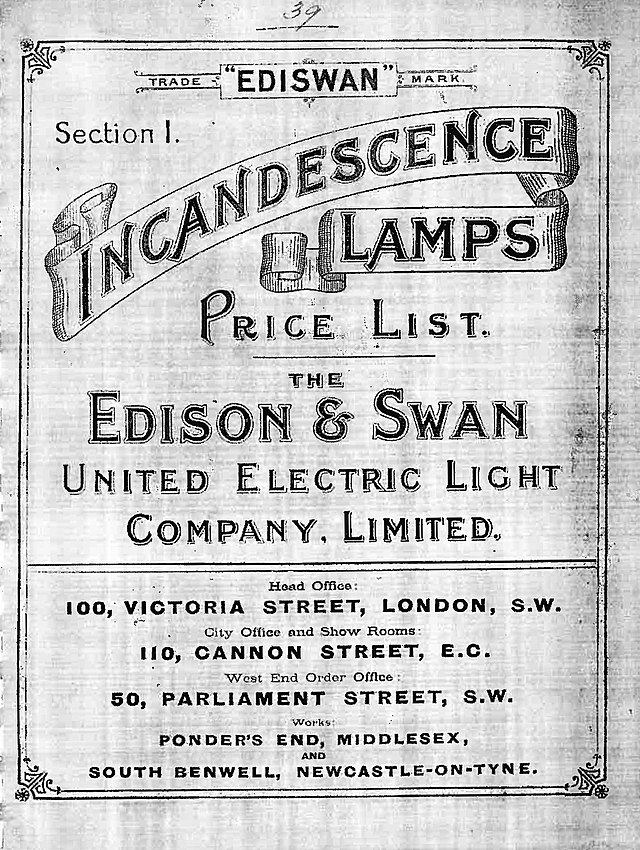

Wanting to avoid another patent dispute like the one with Berliner over his microphone, Edison signed-up Swan in a joint company to manufacture and market light bulbs and he subsequently used a copy of this 'Ediswan Lamp' in demonstrations of 'his' invention.

Ediswan Catalogue 1893 (Wikipedia commons)

The world's first commercial manufacture of Ediswan light bulbs began in South Benwell, Newcastle upon Tyne in 1881, just 2 miles (about 3 kilometres) from the McKie Soda Water factory.

To differentiate between the bulbs, Edison developed the Edison Screw socket. The unique appearance of the Edison version of the bulb helped reduce confusion in the American public's mind as to who had invented it.

The original socket used by both is described in the publication Electric Illumination in 1885: "As in the Swan and Edison systems... When the lamp is dropped into position and rotated to lock the bayonet joint, the heads of its two terminal screws slide over the above-mentioned curved springs... making a good contact, which is rubbed clean every time the lamp is removed or inserted."

Generation of another kind

In Newcastle electricity was the new excitement. To claim that Newcastle was the only birthplace of electricity, as an everyday source of household energy, would be an exaggeration, given the efforts of Westinghouse and Edison in the United States. But it was Swan's electric light bulb in Newcastle that began the revolution and now demanded new methods of generation and distribution.

The young McKie boys, James William Lawson McKie and Thomas McKie, were in the right place at the right time.

At the turn of the century my grandfather and his brother Tom both began training as electrical engineers. Evidently someone in their family had seen its potential (I know, another pun) and paid for their education. It may have been their aunt, Margaret J McKie.

While still in his early twenties Tom had met Bridget Nicholson, who was five years older than he. They were married in 1909, moving to 16 Wansbeck Terrace, Ashington.

Tom and Bridget McKie 1920's

One of the strengths of Tyneside area was technical education. In this, various prominent members of the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society played an important part by endowing educational institutions and persuading the University of Durham to begin teaching science and engineering. Notable among the key players were Armstrong and Whitworth.

Several of the prominent electrical pioneers in the region attended the Durham College of Science and later, Armstrong College in Newcastle, where my father went. It was part of the genesis of the University of Newcastle, that has such illustrious alumni as Peter Higgs, after whom the 'God Particle', the Higgs Boson, is named.

One such graduate of Durham College of Science was John Henry Holmes who in 1883 established J.H. Holmes Electrical Engineering Company.

My grandfather James William Lawson McKie joined J.H. Holmes Electrical Engineering, rising to chief engineer.

John Holmes' business was based on his patented solution to a problem that plagued DC systems more than AC, like those beginning to be used on ships. To quote from Wikipedia:

The "quick-break" switch overcame the problem of a switch's contacts developing electric arcing whenever the circuit was opened or closed. Arcing would cause pitting on one contact and the build-up of residue on the other, and the switch's useful life would be diminished. Holmes' invention ensured that the contacts would separate or come together very quickly, however much or little pressure was exerted by the user on the switch actuator. The action of this "quick break" mechanism meant that there was insufficient time for an arc to form, and the switch would thus have a long working life. This "quick break" technology is still in use in almost every ordinary light switch in the world today, numbering in the billions, as well as in many other forms of electric switch.

A century later the 'quick make-and-break' concept would be a design claim in one of my father's patents. This one for a 'Quick acting make-and-break microswitch' US 3309476 A. Who says memes (persistent ideas) aren't handed on, down the generations?

The adoption of the new electric light bulbs was very fast. To the homeowner and in factories electric light was revolutionary, allowing work to continue through the night. In England then in the US large private homes and theatres quickly installed electricity alternators (AC) or Holmes Dynamos (DC), followed by entire localities.

In Australia the NSW town of Tamworth was the first in Australia to install electric bulbs in street lights and illuminated 13km of road in 1888. In the same State, Young, Penrith, Moss Vale and Broken Hill all quickly followed. Sydney was quite late, mainly because it had recently installed advanced gas lighting with mantels, one or two of which were retained for historical purposes until quite recently.

Trams were originally horse drawn. The first electric trams were installed by the Tynemouth and District Electric Traction Company in 1901. The power was generated at Tanners Bank, North Shields. Like those in Hong Kong the trams were double-decker, on 3-foot 6 gauge track and ran on 550V DC. Hong Kong's still runs but like many such systems Newcastle's was pulled up before WW2 and replaced with busses.

By 1907 J.H. Holmes had installed electric power and lighting into 275 collieries, shipyards and railways, dockyards and quarries; 293 newspaper offices and paper mills; 811 steam ships and yachts; and 148 textile mills. The business, now including my grandfather, also designed portable lighting for ships sailing through the Suez Canal at night.

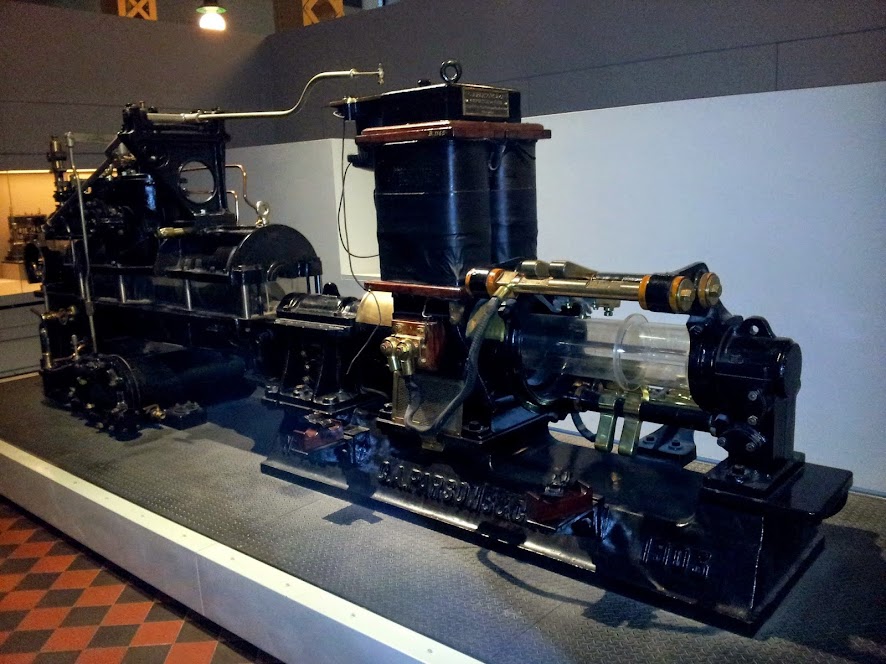

Holmes systems were DC, based on his Dynamo designs. This is a little one:

A 110v dynamo by J. H. Holmes and Co - circa 1900

A 110v dynamo by J. H. Holmes and Co - circa 1900

coupled to a high-speed inverted vertical compound engine,

as may be found generating auxiliary power on a ship

by Browett, Lindley and Co - Exhibit at Bolton Steam Museum

After a fact-finding visit there in 1925, the Institution of Mechanical Engineers commented on the Firm's history: '...the Firm may therefore justly claim to be one of the earliest electrical engineering businesses in the country.' I might add - ' and therefore in the world.'

James William Lawson McKie 1920's

Meanwhile in 1877, Charles Algernon Parsons, a young man who had recently graduated from St. John's College, Cambridge, with a first-class honours degree, joined W.G. Armstrong at Elswick, as an apprentice. Parsons believed in practical learning from the shop floor up, a tradition that both my father and my uncle would carry on a generation later when they would both work for the company Parsons founded. More than that, they would both meet their future wives there.

While working for W.G. Armstrong and later, Clarke, Chapman and Co, also on the Tyne, young Charles Parsons was attracted to the idea that reciprocating engines are essentially complex and irregular, a batch process, whereas a turbine spins a shaft directly, a continuous process.

Turbines, like water wheels, had been around for centuries but there were severe technical and materials science difficulties when it came to matching a steam or gas engine for power. At a lecture in 1911 he explained his thoughts back then:

"It seemed to me that moderate surface velocities and speeds of rotation were essential if the turbine motor was to receive general acceptance as a prime mover. I therefore decided to split up the fall in pressure of the steam into small fractional expansions over a large number of turbines in series, so that the velocity of the steam nowhere should be great...I was also anxious to avoid the well-known cutting action on metal of steam at high velocity."

It helped that modern steel was now available and the metals he now had, as metallurgy advanced, could withstand the centrifugal forces and would deliver tens of thousands of hours of reliable service.

He sold his new engine to the Chilean Navy but the British Royal Navy was dubious of this newfangled technology. So, Parsons built a launch, the Turbinia, capable of 34 knots and ran her in figure-eights around the Navy's fastest ship on sea trials. Turbinia's speed was subsequently demonstrated to Queen Victoria. After that steam turbines were adopted for newly built British destroyers, and continued in use until the County Class, in the early 1960s, important later in my family's story.

Wendy and I recently visited Edinburgh where the retired Royal Yacht Britannia is on display, at her heart are the turbines, developing up to 12,000 shaft horsepower, that power her.

Engine Room on Britannia - showing the turbine engines for one of the two shafts

The high pressure turbine is marked, the low pressure turbine is in the foreground (my photo)

This is a drop in the bucket compared to the 160,000 shp Parsons turbines on Cunard's first Queen Mary, for which my father made blades when an apprentice engineer at CA Parsons. She is now an hotel and attraction at Long Beach California, where I saw her not long after Emily was born.

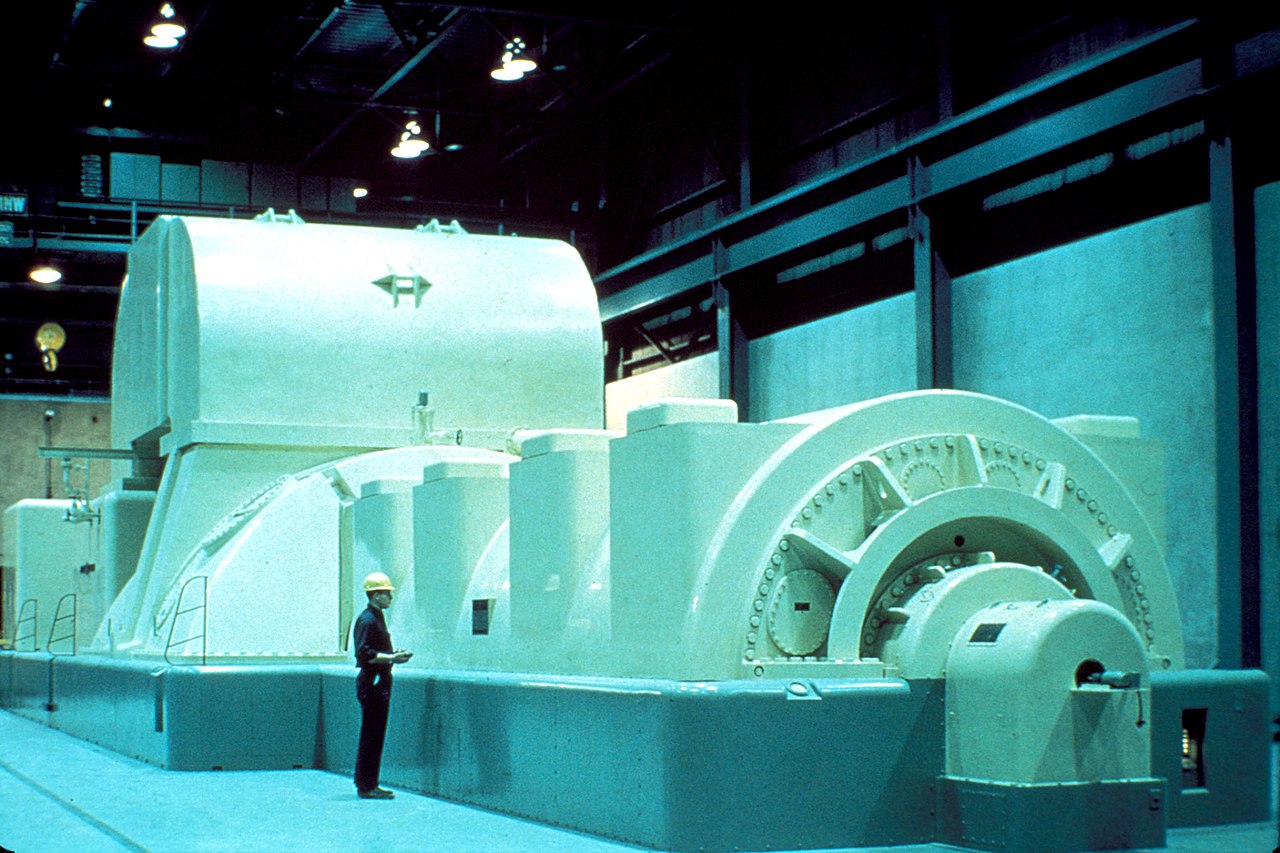

But of much more lasting importance was the application of steam turbines to electricity generation. Parsons coupled his turbine to an alternator in what has become known as a turbo-alternator set. An alternator generates alternating current (AC). The new machine quickly took over from the older reciprocating engines driving dynamos. It was smaller, simpler, cleaner, neater, and therefore intellectually pleasing to a scientist or engineer.

Parsons first prototype turbine driven (DC) dynamo - in the Science Museum in London

Don't be confused by the speedboat in the background.

The turbine is the long brass looking section near the centre - with its top housing removed (my photo)

The first public electric lighting in Sydney was in Hyde Park in 1903, employing a small C A Parsons turbine driven dynamo that can still be seen at the powerhouse museum.

This is that machine (with the upper turbine housing raised 7 or 8 cm on spacers), long since replaced with much larger machines, also initially from CA Parsons in Newcastle upon Tyne.

|

|

|

|

In the image below the turbine is being assembles to drive an alternator (AC) rather that a dynamo (DC).

A dynamo requires a commutator (the device at the front of the red Holmes Dynamo above) that is very difficult to scale up to larger currents. Whereas both an alternator and a turbine can more easily be scaled-up and matched so that now they typically convert superheated steam to up to a thousand megawatts of electrical power per unit.

So today turbo-alternator sets generate over 80% of the world's electricity.

|

|

|

|

Parson's 'turbine motor' is also the direct precursor of the 'gas turbine' or 'jet engine' that now powers the great majority of aircraft.

Parsons came from an aristocratic scientific family famed for practical ability and eccentricity. His mother had learnt blacksmithing to help her husband build the largest astronomical telescope in the world. and his wife Katherine and daughter Rachel and would carry on the tradition after his death. Katherine and Rachel Parsons both qualified engineers would found the Women's Engineering Society in 1919 a pioneering institution that indirectly paved the way for Leander's mother, Emily L S McKie, to become an engineer in the twenty-first century. Initially it was for smart young things of the upper classes. Eleanor Shelly-Rolls (Rolls Royce heir) and aviatrix Amy Johnson were early members.

Charles Parsons was the nearest thing my father had to a hero to be emulated, although he also admired Albert Einstein.

An end to Water

When their father died in in 1910 his younger brother Jacob had taken full control of the McKie water business Northumberland Road.

Both James Junior's sons, my grandfather and his brother, had become Electrical Engineers, abandoning water forever.

Jacob died in 1922 and the mineral water business disappeared. I haven't been able to find out when.

The land alone would have been valuable then and worth a fortune today, it's right in the heart of the commercial district. Maybe it was sold when Jacob died. In any case it's not there anymore. Maybe it didn't survive the Great War or the following depression.

But I wish I had been handed down a few dozen crates of something, because the bottles are now collector's items. A bottle recently changed hands in an on-line auction for £280.37 - and it didn't even contain ginger beer.

By the 1911 census my grandfather, James William Lawson McKie, was a 31-year-old electrical engineer living as a boarder with the Hall family, at 30 Albany Gardens, Whitley Bay, Northumberland.

At number 29 lived a young private school teacher, Margaret (Madge) Domville.

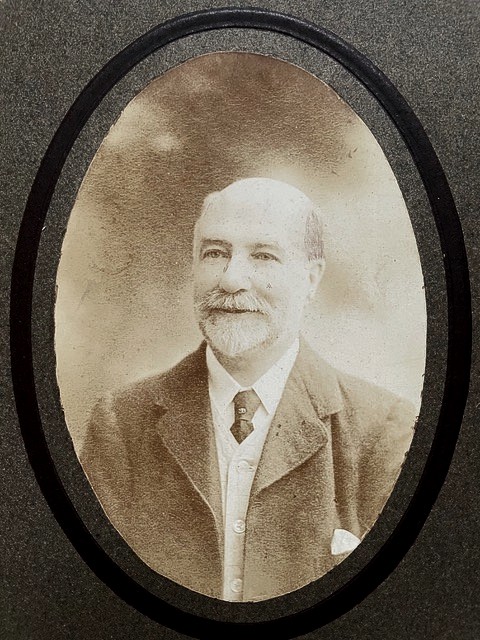

Margaret Domville

Was it love at first sight? Compared to their parents a generation earlier and their siblings, they were both on the shelf. He was 34 and she was 28.

They were married in 1914, at the start of World War I.

James and Madge had sufficient resources to buy a house at 58 Queens Road, Monkseaton, Whitley Bay, also a good address. Their first child, James Domville McKie, was born at the end of 1916. I wonder if an earlier pregnancy failed, as do so many today, with 'older' mothers. According to family lore, neither parent was lacking in libido.

58 Queens Road, Monkseaton today (Google Street View)

It was the middle Great War. James was a bit too old to serve. And in any case he was engaged in fitting out ships, coal mines and factories with electricity - very much a critical reserved occupation. The business was booming and very soon had around 500 employees.