We children were almost overcome with excitement. There had been months of preparation. Tree lopping and hedge trimmings had been saved; old newspapers and magazines stacked into fruit boxes; a couple of old tyres had been kept; and the long dangerously spiky lower fronds from the palm trees were neatly stacked; all in preparation.

The paddock next door was reached through small wire gate. All things needed for the bonfire had been dragged through this gate at different times. And, at last, parents and children had worked together to build our bonfire. It had a carefully allotted position; well away from trees and far enough down the paddock to provide a gathering area; just before the ground fell away towards the bottom corner. Although the time of year was cool and often damp, we knew the heat of the fire would be searing.

First the tyres marked the epicentre; they helped to hold erect the central pole and were surrounded by the boxes of paper, soaked liberally with kerosene; on top of these were heaped a year's worth of tree branches and hedge trimmings some quite hefty; and finally the palm fronds gave the whole a satisfying wigwam appearance and protection against possible rain.

In case of emergency hoses were at the ready, fed through the hedge to the taps in our garden next door.

Now the house smelt of cocktail frankfurts; homemade sausage rolls and orange cordial. Platters of food covered the dining room table. The mothers gathered in the kitchen and dining room. The men back from adding the final touches; the length of 1” water-pipe sledge-hammered into the field, now pointing skywards for rockets; tall grass mowed or stamped down; kerosene ‘hurricane’ lamps strategically hung; now gathered in the lounge room in their big jumpers and wartime coats, with cigarettes and glasses of scotch; memories of the War not far behind.

Empire night, 24 May, had already become an annual ritual for our family and our neighbours, the Spencers, as well as our extended families and various regular guests.

For the hundredth time Peter and I reviewed the contents of our fireworks boxes: strings of tom-thumbs, many little crackers attached by their wicks in two rows so that they exploded in sequence; double-happys much the same but larger; then the individual crackers or ‘bungers’, the smaller penny bunger and the giant twopenny (tuppeny) bungers. We also had an assortment of non-exploding ‘pretty’ fireworks, like mount Vesuvius and mount Etna; 'roman candles' and some semi-exploding fountains that periodically fired out stars. Catherine wheels of various sizes needed to be expertly nailed to a post to successfully create their disk of colourful sparks; and of course 'jumping-jacks' that bounced about randomly exploding at each jump. But the best of all were the rockets.

The biggest rockets had been purchased by daddy in town (Sydney) and were always carefully horded for the big night.

Different fireworks had different wicks. Pretty ones and rockets typically had blue touch-paper and bore the famous injunction: ‘ignite the blue touch-paper and retire’.

Bungers (crackers) consisted of a quantity of gunpowder bound tightly in a roll of paper. Through a clay plug at one end was a grey stringy wick that on the larger ones was doubled over. The wick was made of thin ‘cigarette’ paper coated on one side with gunpowder then rolled into a string. This quite predictable fuse allowed them to be held to a flame or ember until the wick started and then to be thrown to a safe distance.

By the end of May most Australian boys and many of the girls had already spent at least a month letting-off bungers and small rockets; often in mock battle. As soon as ‘crackers’ began to appear in the shops they became the focus of our attention. Strings of tom-thumbs and double happys were disassembled so that we might never be without an inexpensive little explosion when the occasion, as it frequently did, demanded one.

Tom-thumbs - close to actual size

While older boys might carefully hold a tom-thumb until it exploded a double happy was a much scarier proposition and needed to be dropped to the ground or thrown once the wick was alight.

The suburbs resounded with a constant background of little explosions. The smell of burning gunpowder filled the air.

The larger bungers were too expensive for casual use but had much more interesting applications; more of this later…

At last it was dark enough to begin. My father Stephen, the host with his fancy cigarette lighter, was supported by pipe smoking, future Commissioner for Scouting, John Spencer; matches at the ready (be prepared!).

Children stand back! We did. The men skirted the wigwam; bending down here and there with their little flames like circling Indians in a fire dance.

Sydney Morning Herald, 25 May 1955

Disjointed flickers of flame soon grew larger consuming from within; first the noise began; then the flames burst out and with a roar a huge tower of flame and sparks leapt into the cold night air. We fell-back assaulted by a wall of heat; it was fantastic, terrific, awesome.

In a little while the fire’s first fury was over and it became approachable; time for the fireworks.

But somehow these had started early. Colin Spencer in his excitement had abandoned his shoebox full of fireworks and left it lidless as fire’s first sparks rained down.

Somewhere in the box blue touchpaper had begun smouldering.

Within seconds of the first ‘pretty one’ starting to spew its sparks, every wick in the box was alight.

Rockets flew horizontally amongst us; jets of fire squirted in all directions; bungers blasted the burning box to smithereens. It was all over in a minute or two. Colin was inconsolable; made the worse because this was now part of the tradition. The same thing happened to him last year!

But the rest of us had plenty to make the night a success. Our rockets arched upwards; our bungers banged; wheels spun; colourful sparks drew oohs and ahhs.

In due course the fire was damped enough to be left and we retired to the house for cocoa; our clothes smelling of smoke and gunpowder; assorted minor burns to be washed and dressed.

Next morning the bonfire was still smouldering; a pile of white ash and at its centre coils of wire; all that was left of the tyres. It was time to look for the fireworks that had not gone off and to give them a second chance in the smouldering embers; morning-after fun.

You can read more about Australia's historical enthusiasm for Empire Day in this article from the National Library of Australia.

Cultural Change

On reading through my little story and the one from the National Library I am struck by the changes in our society that it illustrates. How many people remember Australia's enthusiasm for Empire; the school assemblies; school recorders playing 'God Save the Queen'; exhortations to loyalty; the coordinated calisthenics, the folk dancing and may-poles and so on. In part this was because of a deeply ingrained sense of isolation and cultural inferiority and a need to be part of something bigger.

Seen from today's boisterously self-confident Australia it is difficult to believe that things could ever have been so.

But the story also illustrates just how much increasing urbanisation has restricted some of our freedoms, particularly those of children, who now more often learn by being told than by doing.

Australia had no TV until 1956 and then it was a black and white service restricted to the early adopters. Children, as in earlier generations, needed something to amuse us during the long school holidays. Our parents gave us far more freedom and were generally happy if we were exploring in the bush; engaged in some experiment; building something; or pulling something apart and reassembling it.

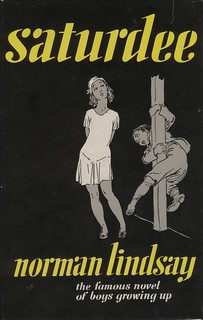

The books we read at the time seemed to encourage independence like 'Treasure Island' or the 'Sherlock Holmes' series. Even Enid Blyton's 'Famous Five' and 'Secret Seven' series had children going out alone for days on end. We never did that - we got hungry. Norman Lindsay's 'Saturdee' provides a comic recollection of childhood fifty years earlier.

It has more in common with my childhood than mine has with those of my children.

The Empire

In hindsight it is easy for me to understand the initial enthusiasm of our parents for this annual Empire Night event. The War had been over for less than a decade and the British Empire was apparently victorious. That it was mortally wounded was not yet evident.

Australia had played its part. Initially the Empire had stood alone against the Axis powers. When on Sept 3 1939 the Prime Minister had broadcast "Fellow Australians, It is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that in consequence of a persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her and that, as a result, Australia is also at war"; there was no debate; Australia was part of the Empire and the Empire was at war.

Unlike Anzac day there was no overt celebration of war but similar expressions of patriotic sentiment surrounded the day; particularly at school where we had a half day; on the wireless (radio); and at the pictures (newsreels). The new, young Queen made a speech about filial ties across the Empire: Canada Australia, New Zealand South Africa, Rhodesia and all those smaller countries from the Bahamas to Burma; the map for the world was mostly British pink.

‘God save the Queen’ was sung as our National Anthem; said as a toast; and meant. There’ll Always Be an England and Britannia Rules the Waves were almost as popular.

In the 1950’s our fathers were still young men; in their thirties. Bonfire night gave my father the opportunity to dress in his RAF fighter pilot’s Irvin jacket and pants. With his, still black, hair oil slicked and stylishly combed back he have might have just left his Hurricane; perhaps parked up on Pennant Hills Road. As he stood transfixed, illuminated by the roaring flames, alongside John Spencer in his Australian Army Greatcoat, they might be watching a downed Messerschmidt or Zero burning; or worse, the death of a friend.

Even our mothers seemed caught up in this spirit; they were organising food for the troops.

These scenes with local variations were being repeated all over Sydney; and Australia. Many back roads were still unsealed and ashes of large community bonfires could be seen darkening the dirt throughout the suburbs the following morning.

Although the patriotic sentiment seemed almost universal there were already dissenters, whose voices became louder as the years passed. Apart from the Australian Republican movement there were the Marxists and a growing group of ‘free thinkers’ like the 'Sydney Push' who condemned the ‘wowserism’ of conventional society and promoted a wide range of liberal, and sometimes libertine ideals including the ‘beat’ culture. Each in their own way gave voice to a suspicion that the day, to the extent it was not about letting off explosives, was about ’jingoism’ and each ridiculed for different reasons the concept of ‘Empire’.

In the fifties Australia was still getting over a period of Christian sectarian conflict. There had always been some Roman Catholic reticence to 'Empire' day, the Sydney Archdiocese having renamed it Commonwealth Day as early as 1911. Of course Australians were well aware of the English tradition of burning the Catholic plotter Guy Fawkes in effigy; albeit in November when it is impossible to light a fire out doors in most of Australia; unless you want to see your entire property consumed. But some bonfires followed this tradition. I can remember being told not to put an effigy on ours; I didn't know why at the time. It was probably out of deference to our many Catholic friends, in particular our other neighbours, the McDonalds.

By the end of the 50's it was clear that something had begun to go wrong with the British Empire. Palestine and Northern Island had become and insoluble problems and ongoing strife on the sub-continent highlighted the failure of partition. Perhaps the death rattle began with the Suez Crisis in 1956, in which Australian PM Bob Menzies tried unsuccessfully to mediate; or perhaps it began earlier with the loss of India, Burma and Palestine in 1947.

The popular and political enthusiasm for Empire Day waned. Bonfire night was moved to June, the Queen's Birthday, and it was officially renamed Commonwealth Day.

Initially Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa had formed a British Commonwealth under The Statute of Westminster. For Australia this was not ratified until 1942, during the war. But a new broader Commonwealth that previous colonies were encouraged to join was in the making. This was immediately confronted by the issue of Apartheid in South Africa, leading it to be forced from the Commonwealth in 1961; followed by Ian Smith’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in Rhodesia in 1965.

Like a decaying carcass bits were beginning to drop off the old Empire. Previous colonies left or were cast off at a bewildering rate. But the final straw, that reduced the Commonwealth to a loose association of countries with sport and sometimes a figurehead in common, was Britain proposing to join the European Common Market: first in 1961; again in 1967; and finally, successfully in 1973.

As a consequence Britain and progressively abandoned Commonwealth trade preferences. Australian primary producers accused Britain of turning her back on them; and preferences for British goods were removed in retaliation. British financial ties weakened and US investment increased. In 1966 Australia moved to decimal currency then abandoned the Sterling currency zone altogether just a year later.

Throughout the 1960's the break with British imperial sentiment continued. Although we had fought with the British during the Malayan emergency and hosted British atomic bomb and rocket tests we no longer valued the Imperial alliance and joined with the Americans under the ANZUS treaty, contributing to the Vietnam War as a proof of commitment.

We no longer had a British appointed Governor General or State Governors and legal appeals to the Privy Council were removed. In addition to our new plastic money we had a new national anthem and Australian passports. We abandoned imperial measurements; developed our own cuisine; music; theatre; films; contemporary artists. We now had our own dictionary; and acquired a new broadened accent; no longer did educated Australians aspire to an English voice or eschew vernacular Australian expressions. Australia had become the host to a vast number and variety of immigrants from all corners of the world, each contributing to this mix, and they had no sense of Empire; or its traditions.

We had become our own people; and we determined to compete as equals with Britain as with other nations. We stopped looking to Britain as the sole source of culture and wisdom; suddenly other nations had something to offer too. And we began to notice that Britain now often looked to Australians for entertainment; intellectual chatter; and Man Booker Prize winners.

So as the years passed; the bonfires became smaller, at the local school or scout hall and eventually fireworks and even spontaneously lighting fires, without a lot of permission, was banned.

Fireworks now require a special licence. But somehow firework events are much more frequent. There is hardly a weekend without a display on the harbour somewhere; and most displays are massive affairs sometimes costing millions of dollars. I can hear fireworks now as I write; they make much louder bangs than ever we did.

But non of these fireworks any longer celebrate our membership of the British Empire.

Bonfires

In the country it is still possible to have a good old spontaneous bonfire but this pleasure is lost to city folk. Now it is impossible to have a larger fire outdoors in Sydney than is needed to BBQ a string of sausages.

But for many years a common weekend pursuit of gardeners in leafy suburbs was to rake the leaves into the roadside gutter or into a pile in the backyard where they would be set alight. In Sydney the weekend was synonymous with the smell of burning leaves and grass clippings. These fires could on occasion be quite large.

Now this is such a distant memory that it seems incredible that when Brenda and I bought our first house in Paddington in inner Sydney we dragged the entire cockroach infested kitchen, benches lower and overhead cupboards, the lot, out into the small terrace-house backyard, together with several wardrobes other junk furniture and some disgusting carpet; and set it alight. The resulting conflagration was so intense that everything was reduced to ash within an hour. Not only were the cockroaches eliminated but we got rid of most of the unwanted vegetation in the overgrown garden.

We didn't give it a second thought; Sydney has a system of fire alerts to advise when lighting fires is safe. It was cool weather and we had the hose at the ready in case the intense heat set fire to the fences. No one complained; no one called the fire brigade. Setting a bonfire to get rid of rubbish in a backyard was accepted practice. I know of another young couple, Sally and Murray, who had a backyard completely overrun with lantana on a suburban block in inner suburban Naremburn. To clear it they simply cut it away from the fences, piled it into a huge bonfire and set it alight.

Crackers

Crackers as I have already explained were exploding fireworks (the word like many others in Australia is onomatopoeic like ‘chook’ – a chicken). Almost all crackers were based on gunpowder (or black powder) although it was rumoured that country lads preferred ‘half a stick of jelly’. We wished!

The ones bought at the newsagent or variety store mostly came from England or China. These had their uses straight out of the packet. For example we had a length of ¾ inch OD steel water pipe threaded at one end and a chrome plated brass cap that screwed over this, through which we had drilled a hole large enough for a wick.

‘Penny bungers’ came in a ten inch package of forty, four bundles of ten. These were ideal. The wick was fed through the hole and the cap screwed on tight. A paper wad was pushed down the tube with a piece of dowel followed by a standard glass marble and another paper wad. Initially Peter held the ‘bunger gun’ as he was the only one brave (or silly) enough - he was younger. But after we had tested it on some trees, the marble becoming well embedded finger deep or blasting sizable splinters off them; punched a few holes in a sheet of corrugated steel and some seedling filled kerosene drums; we deemed the experiment a success. It was less successful when elevated at 45 degrees for maximum range as the marble simply disappeared into the distance and we had no way of determining how far it went or where it landed, one block, two blocks, three blocks? For some reason our experimental apparatus was confiscated by our parents after the holes in John Spencer's drums were discovered.

In a similar experiment we found that an axle stand consisting of a foot of 3” steel tube welded to a 6” square plate made a wonderful apple mortar. Our other neighbours, the McDonalds, had a prolific apple tree, green Granny Smiths, providing plenty of ‘bombs’. These needed to be just a little bigger that our tube. It required coordination; one would light a twopenny bunger and throw it into the tube; the other would ram down an apple. We found we could shell roofs several hundred yards away; even those hidden by tall trees. Most satisfying were the local chook sheds; where a hit would unleash a fit of squawking.

But these were the simple application of commercial toys. We wanted bigger stuff. We explored two avenues: using the contents of several commercial crackers to make a bigger device; and making our own explosives. In the first case Michael McDonald had older brothers and they had made some ‘basket bombs’ using commercial gunpowder and cotton reels. We were inspired.

Down the road towards Pennant Hills was a handkerchief factory that often threw out large commercial cotton reels. These were made of wood and occasionally had some remaining thread on them; those were preferred. They had a good sized hole down the axis large enough to take the gunpowder from several bungers. Our only remaining problem was how to block the ends. Here we almost came unstuck as we used the conventional clay plug. This wet both our wick and our charge and needed to be dried out for much longer than our patience allowed. As I remember only one went the distance. It was duly posted in the chosen letterbox and the result was so spectacular; and satisfactory; and scary; that we never repeated the experiment. We learnt the value in a long wick and being fleet of foot.

Commercial bungers continued to be a source of amusement for many years. Like many others, I always had a few at hand.

Decades later, when I was an adult and married, a friend of mine, Richard Brady and I would exchange bungers when leaving from or arriving at each other’s homes.

As one entered his garden, after descending in the lift, an explosion close overhead was likely to farewell you. Their unit was at the top of the building and the bunger with its sparkling wick could be seen tumbling down. As a result I installed an electrically triggered bunger device in the hydrangeas near our front door to farewell him and his wife Jenny. I generally waited ‘till they were leaving; I didn't want any accidents with undrunk bottles of wine as they arrived. Occasionally other close friends were similarly fare-welled. I was recently reminded of this by Craig and Sonia, our travel companions in South America.

To announce our imminent arrival Brenda and I worked as a team to light the fuse on a bunger that I then fired high into the air with my catapult. I had perfected using cello-tape to stop the wick being blown out as it flew.

It must have amused the neighbours. I can’t understand why they banned those things - they were so much fun!

It was a sign of the times that this behaviour was generally tolerated by one and all. Brady was a leading and very successful lawyer; I worked in technical marketing for Australia’s largest company; pillars of the establishment. It seems that many people did things then that would be likely to get them arrested today.

Making gunpowder

Gunpowder is a kind of cake consisting of saltpetre (potassium nitrate) sulphur and charcoal (carbon). Although the ingredients and their proportions are well known the actual process by which these are combined into the cake is critical to the outcome.

When we were very little boys Colin Spencer somehow learned that saltpetre was obtained from wood ash. So we busied ourselves collecting ash from assorted fires and fireplaces and making a sort of witches brew in the Spencer’s garden. Needless to say we new nothing of separating salts by their boiling temperature and the exact process by which we would separate the saltpetre from this mess eluded us; but we had hours of fun and got very dirty.

Even with ready pocket money we found potassium nitrate impossible to buy as it was assumed that a grubby, or even a well dressed well spoken, little boy wishing to buy a pound or so had only one goal on their mind. Even years later, in high school chemistry, the more effective nitrates and other high energy oxidisers (like potassium chlorate) were kept pretty secure from unauthorised experiments that may require a new science wing.

Those little boys that did manage to get some 'nitre' often came to grief as all the ingredients need to be ground very fine to make a successful black powder and attempting to grind potassium nitrate with either carbon or sulphur is likely to result in combustion; all three in an explosion. It can be a very dangerous process. Their lost hands and eyes contributed to the eventual ban on fireworks.

As buying potassium nitrate was too difficult we decided to base our experiments on sodium nitrate, available in nice big bags from the gardening shop. Ground up with sulphur and charcoal then dried in the sun, or rinsed with methylated spirits, to remove water this makes a very passable fizz but it is hygroscopic and very difficult to keep dry as a result.

In an early experiment I decided to make a porridge of the ingredients in the correct proportions in my mothers Pyrex coffee percolator that had been a wedding gift to them in Canada. It turned out not to be laboratory quality and cracked after a short time on the heat; the contents pouring all over the stove. I was not popular.

By the time I reached high school we gave up the attempt to make gunpowder in favour of much easier to make explosives like ammonium tri-iodide (nitrogen triiodide). But we learned quite a bit of chemistry and some physics to boot and had a lot of fun.

The strange thing was that in those younger days all we wanted to do was make explosives that went bang and instead went fooshhhh. Later when we took up making rockets we wanted them to go fooshhhh and they more often went bang!