Australia

It was continuing health problems from his war service that caused Stephen and his family to abandon Newcastle upon Tyne to seek a warmer climate, 117 years after William and Margaret McKie had abandoned Scotland for Newcastle.

Pragmatic as ever, Stephen built a powerful shortwave receiver and they started listening to broadcasts from South Africa, New Zealand and Australia, where young men he had trained to fly had come from. These quickly confirmed Australia, and specifically Sydney, as the preferred destination.

As I have mentioned Stephen's older brother James Domville McKie also trained at Parsons. He completed his engineering qualifications during the war. He married Joyce Smith and they began a family, conceiving my cousin Sheila in 1944. But demobilisation required engineers. Jim was called-up and in August 1944 was commissioned as an engineering officer in REME and sent to India, soon to decommission war equipment, so that secrets would be preserved and to avoid a glut of war surplus equipment like the gluts that had caused previous post-war recessions.

After his return he was employed by Glover's Cables, a company manufacturing high voltage, gas insulated, cables of the kind used to distribute the grid underground in major cities.

As chance would have it, Jim was posted to Australia to head-up Glover's technical support in Sydney, much to my mother's chagrin because it looked like we had followed them.

So, in August 1948 my parents sold up their home and packed up their two infant sons and flew to Sydney to establish a new life. Obviously, they had had a mortgage and flying was very expensive then, so they arrived in Australia with very few financial resources remaining.

Stephen's first job was with the National Standards Laboratory, then at Sydney University.

Stephen and Vera in Sydney - winter 1949 - hand coloured

They had a great project for a young Novocastrian Engineer: to develop stress gauges and related instrumentation to check the stresses in the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The Bridge was designed by the British firm: Dorman Long and Co Ltd of Middlesbrough, before the days of computers or finite element analysis.

A similar rail-only bridge had already been built in New York over the Hell Gate Narrows of the East River.

Hell Gate Bridge - over the East River in New York - completed in 1916

Again, I have my own photo somewhere - but this will have to do

Photo: Detroit Publishing Co (Wikipedia Commons - cropped top and bottom)

This inspired Sydney's Chief Engineer, Bradfield's choice of design. But the Sydney bridge was to be a fraction longer, higher and considerably wider. So, to verify their design concepts for this innovative undertaking Dorman Long began a similar but much smaller and simpler bridge first: the Tyne Bridge in Newcastle upon Tyne.

For Stephen the job was like 'Taking coals to Newcastle' but it was unlikely that he had seen the American bridge on our way over. You need to be up high. We had a good view of it when I lived there in the late 1970's.

It turned out that the Sydney bridge was substantially over-designed, making it one of the heaviest steel structures ever built. But that was all to the good as the steel specified was imported - you guessed it - from England.

But Sydney and NSW got the last laugh. The project was financed with a very long term, very low interest loan from London. The interest rate was so much below the usual cost of finance that the NSW Government didn't pay it off until the end of the century, when it was virtually petty cash due to inflation.

The approaches and associated underground train and tram infrastructure also consumed a vast quantity of steel. This made in the NSW town of Port Kembla and in Newcastle NSW. The works themselves and new the transport systems that resulted, continued to provide employment for thousands in the State all kindly financed by British loans - right through a World Depression.

|

|

|

Two iconic bridges like the earlier one in New York (my photo)

The principle is the same but the execution is quite different for the larger bridge

From there Stephen moved to Amalgamated Wireless Australasia (AWA) when it was still majority government owned after taking a critical communications and manufacturing role before and during the war. But Stephen would soon be on his way to the private sector.

With both McKie brothers in Sydney I grew up with chatter at family gatherings about electrical explosions; and switches; and arcs; and generation; and how stupid some people can be around electricity.

After AWA Stephen sold electronic instruments and research equipment, I remember PH meters, for Philips Electrical Industries (Philips of Eindhoven) then he, bizarrely, became Assistant Manager at the Johnson & Johnson. I remember wide ribbons of fluffy fabric passing through a machine in their tampon factory in 'The Rocks' in Sydney.

Actually, tampons were not the only product they made. They also made Modess sanitary pads but it's the tampons I remember. The machines sometimes played up and we had a bag of sample rejects in a cupboard at home that peter and I used for cleaning things. I had no idea there was any alternative use, until one day my mother came rushing out to stop me getting the grime off my scooter with one in the front garden. I used to ride my scooter to school until it was stolen when I was in fifth class. It's probably as well I hadn't taken one to school for emergency grime removal. They had a convenient string, just right for tying to the handle bar.

He was there very briefly, taken aback by their culture of long and boozy lunches, before becoming the Factory Manager at the Sefton Works of Australian General Electric (AGE): manufacturing electric ovens; washing machines and flat-plate ironing machines.

Stephen McKie, Manager Sefton Works

Australian General Electric was owned jointly by General Electric, from America, and Associated Electrical Industries, from Britain. Set in the same time frame, the television show 'Mad Men', looks like kindergarten compared to the ebb and flow of internal politics between British and American and local interests at AGE. It was all cocktail parties and wives dressed up in cocktail dresses and high heels at one end of the room discussing women's interests and the men at the other discussing business decisions and who they did or didn't agree with, according to the power struggle state of play, and almost everyone smoking.

Vera at the AGE Staff Ball 1952

the strange doll on the table was an early 'Hotpoint' advertising mascot - happy Hotpoint

After an internal, internecine war GE was forced to withdraw, due to an anti-trust action, and in 1955 AGE was transmogrified into AEI - Australian Electrical Industries, now fully owned by AEI of the UK but still licensed to use the GE brand name 'Hotpoint'.

At cocktail parties, we children had to be in our best clothes and on our best behaviour, offering around hors-d'oeuvre then going off to play quietly and intelligently.

At the works Christmas Party, we couldn't join in with the other kids or go on the great little train, even though we went to a very ordinary State primary school at Thornleigh and could mix it with anyone - including the occasional black eye received and/or inflicted. We had to be the impeccably behaved kids in the suits hanging around the adults.

Around 1952 - Peter in the middle

Around 1952 - Peter in the middle

That wasn't my mother's only necklace

We learnt the family's double standard. At home our parents were often playful, squirting each other with the hose or slapping, pinching and tickling. They weren't nudists but we all went to and from the shower or bath naked and seldom shut the bathroom door. When the mood took them, they sun-baked naked on our back lawn. But in public they were quite proper and formal, particularly as the work environment became increasingly Machiavellian.

Meanwhile managing a factory with a couple of hundred employees was never dull. There was an occasional industrial accident but the worst was a man on the way to work who jumped onto the platform at the local station from a train that wasn't stopping. In those days there were no automatic doors or air-conditioning so people kept the doors open.

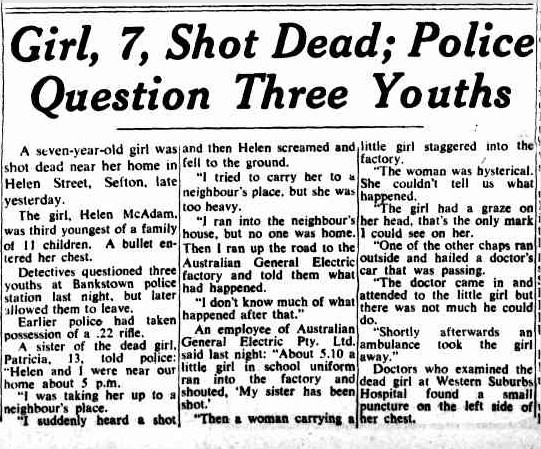

Even walking in the streets had its dangers back then, like kids with rifles:

The Sydney Morning Herald - Sep 28, 1954

A family of 11 children... one of the other chaps...

It was a different world - the careless kids lost their rifle

As a result of this internecine manoeuvring Sefton and another factory, Villawood I think, was closed and manufacturing was consolidated at a bigger plant in Marion St, Auburn. Stephen was relegated to Assistant Manager, a position he disliked, and somehow had himself shifted sideways into the shiny new research and development facility instead. In this he had the support of the local British appointed head Harry George. He and Vera remained friends with Harry and his wife Marjorie for many years after AEI. They had a stunning daughter, Pricilla, who was perhaps a decade older than me. Just as girls became interesting, I fell secretly in love with her but she scorned me.

Stephen had taken himself out of the political limelight and into a career backwater because the Machiavellians, with their objectives set a few days ahead, rather than months or years, saw no immediate use for R&D.

Stephen - AEI Product Development Department

Notice the secret wall oven - I have this photo because it was rejected as revealing too much

But back in research and development Stephen was 'happy as a sandlark' and got to delve into all his beloved interests including high voltage switchgear. I went to work with him once in the school holidays when they were testing new plasma dispersion designs and arc suppressors for high voltage breakers, of the kind used in electricity sub-stations. One of his team told me that if McKie put on his glasses they knew it was time to get behind something solid.

They were also engaged in developing new domestic appliances in the context of utility, electrical safety and ease of manufacture, like the wall oven in the photograph above and a pedestal fan. Another I remember was a 'table griller' (code name: 'table gorilla'). One of the draftsmen had drawn a cartoon of a gorilla sitting on a table that Stephen had framed. But AEI would never take it to market. Indeed, soon they wouldn't take anything innovative to market ever again. Eventually what remained of the failing appliance division would be taken over by Malleys, a competitor that was itself absorbed and absorbed again. The remnant of company was not finally wound-up until 2008. The cancer of internal struggles for personal advancement by technical illiterates was complete.

Stephen's appliance development team was vindicated a decade later when Sunbeam successfully marketed their almost identical 'Vertical Grill' in the 1970's. People still love the Sunbeam product 40 years later because it both toasts (bread or sandwiches) and grills meat on both sides at once with no cooking oil or fat. They now sell for around $200 on eBay - no planned obsolescence there.

Throughout this whole period of his life, he followed his father's example and made and invented things at home.

Until we moved to a bigger house, the corner of our kitchen was a workshop with a solid worktop and a small vice. The draw below contained small hand tools. The cupboard under it contained sheets of metals and various insulators, including asbestos and larger tools. Likewise, the cupboard above contained other materials and tools and on top were flasks of various chemicals, including plating solutions containing cyanide. There were lots of containers of screws and rivets and small drill-bits and taps and dies.

It was conveniently adjacent to the electric oven for baking things like insulation and the sink for quenching something hot. In the laundry we had a small cast iron gas cooker with a long burner and a smaller round one that were just right for heating soldering irons of different sizes. Even the bathroom was used to test fast revolving disks that might break-up. It was our closest room to a concrete bunker.

My mother was a keen and able cook and she could be making a meal or baking a cake in her part of the kitchen while Stephen was drilling of filing something in his.

At different times the sunroom or garage got taken over for projects or little home industries. He made a number of patent applications and went on to patent several of these.

When he was at Philips as a sales engineer, Stephen developed an infrared security system that reflected off mirrors on posts around our garden and could also be used to count traffic on Pennant Hills Road and several other such tasks. Although they did not employ him in any development role whatsoever and the device was unlike anything they sold, Philips forced him to sell the rights to them and then shelved it.

The Dutch-born head of Philips in Australia, Franciscus Nicolaas Leddy, was responsible. One day in the mid 1950's Leddy was shot, non-fatally, while leaving the company office in the City. My father had left by then but he was much amused by the large number of ex-colleagues whom the police investigating the shooting thought were suspects. No one got caught. Stephen claimed to have told them - I think it was his joke - that a shorter list would be of those who didn't want to see Leddy dead. There's probably a Limerick in there somewhere: 'There was a sly Dutchman of Philips...'

On another occasion Stephen designed a prototype high frequency filter for a local radio company and then built a coil winding machine, using Meccano gears and a sewing machine motor. He and my mother then made several hundred, or perhaps thousand, cute little IF transformers and other radio coils. They had white plastic bases about 2cm square with up to half a dozen pins pushed through, to which my mother soldered the wires and little white capacitors, in a production line. The forma on which the coils were wound was made from a brown compound tube about 7mm ID. Into this slid a ferrite tuning core on a brass screw shaft. An aluminium can over the top completed each neat little device.

Another time he built a machine to be used by a factory somewhere to electrically seam/spot-weld little mesh cylinders, used as filters in agricultural sprays. He and I, when I was aged about nine, went to our favourite haunt: Hare & Forbes (Hairy Forbes) in Parramatta, a war and industrial surplus barn that was like Aladdin's cave to me. He chose a large transformer that we, I 'helped', stripped the core and outer windings from, replacing the secondary windings with long wide strips of copper sheet insulated with an intermediate layer of shellac treated craft paper (my job) to deliver just a few volts but a massive current. The core was then reassembled and this became the heart of the welder.

Years later when Peter and I were students and 'playing cars', I rebuilt a transformer almost the same way to match with newly available high current silicone diodes so that we could turnover a car engine without the need of a car battery. It was brilliant for jump-starting.

On a later occasion I went with my father to 'Hairy Forbes' to gather components, mainly thumping big relays like those once used in lift motor rooms, for a test panel, to be used on a production line manufacturing home appliances.

One of his projects was non-electrical and strictly low-tech. We called it the Foofer. It consisted of a solid yard long wooden rule set vertically in a wooden base. A chrome plated bracket carrying a cylinder of powered French chalk could be set at any height along this. Attached to this cylinder was a long rubber tube and a rubber squeeze bulb fitted with one-way valves. So that when the bulb was squeezed a jet of French chalk was ejected horizontally. In fashion shops and dressmaker's, woman would turn in front of this device and set at any desired height, it would mark an exactly horizontal hemline as their dress hung on them individually.

He subcontracted out various components to other men in the neighbourhood and sold several hundred. I continued to see them when my mother bought clothes years later. I was bound to strict silence - once was enough. No more exclaiming: 'Look, there's one of daddy's Foofers!'.

At different times we had plating baths for different metals in the garage, latterly for silver, together with a trichlorethylene (now trichloroethylene) vapour degreaser.

When people criticised my spelling, he would tell them that I could spell 'trichlorethylene' and 'carbon tetrachloride' both of which we had in big brown bottles on top of the kitchen cupboards. I could because they are among the few words spelt sensibly, not like: further, father, weather or indeed most words in English. These you just had to remember and when you couldn't you had to come up with a different way of writing it, hopefully in words that you could spell.

This was an endless handicap for me in school. But at least it improved my vocabulary. Stephen was sympathetic because he had had the same problem at school. My frustrated mother just couldn't understand what my problem was. She had me tested - nothing wrong with the kid's IQ - he just can't spell. In this I've had the last laugh. Being able to spell correctly is now a redundant ability thanks to computers. Go suck Mr Perkis!

Stephen's various profitable projects paid for a holiday or a new (old, different) car, or something. Many turned out to be break-even and were just for fun.

Initially, when a sales engineer, it must have been with Philips, Stephen drove a little Ford Prefect. It was post-war rubbish. Bits frequently fell off it, including on one occasion on the way to Newcastle Australia, the carburettor, saved only by the fuel line. But it was a company car and could fit in our garage.

Then when he got the AGE job and needed to drive to Sefton at the end of 1951, he bought a large straight-eight 1937-38 pre-war Hudson.

We thought it American but it had been assembled in Australia, due to the industry protection laws at the time, and did not have to be converted from right hand drive. There was no possibility of it being housed in the garage, unless you wanted to climb out of a window. From then on, at 317 Pennant Hills Road, all our cars lived outdoors, two of them on the side lawn. The garage became, at different times, a storeroom and workshop.

The Hudson in 1951 - me, Peter, Vera

It's at Collaroy Beach in the winter - there's another photo that makes that clear

The Hudson needed a lot of work, including an engine overhaul and paint job, but eventually it ran smoothly, except when Stephen tried a new invention that injected water and partially opened the intake manifold when idling or running downhill to save fuel. Then it sounded like an 'ack-ack gun' and people ran out of or into their houses.

This was the least successful of numerous additions he made to his two first cars in Australia, including a spark monitor, window demisters and a fuel consumption gauge, in addition to the more usual battery voltage and ammeter. The Hudson was great on tar roads but hopeless on rutted unsealed country roads, like the one beyond Canberra to Cooma as we discovered one holiday when we were ignominiously overtaken and left in his dust by a Holden that had superior suspension, honed for the 1953 'Redex Trial' car rally around Australia.

One breeze that fluttered the curtains across my father's past was when his youngest sister Joan, no longer at Parsons but now a young Nurse, came to Sydney and stayed in our sunroom. For a period, it was renamed 'Aunty Joan's Room'. But then she found other accommodation nearer the Hospital. As I recall it was at Rose Bay. There may have been a man involved. I particularly remember her being dismissive of a popular song that asserted that: 'Love and marriage go together like a horse and carriage'. The versions I remember were by Frank Sinatra, who made it popular and Doris Day who, as it turned out, didn't believe it either.

After a couple of years, in the 1954, Aunty Joan returned to Newcastle in England.

Aunty Joan departing Sydney forever in 1954

The Sydney McKies +1 less Stephen - taking the photo

Sydney people may be struck by the 50's skyline before all the high-rise buildings

and look at all the rigging - on a steamship

In England she got married in 1962, and had a daughter, my cousin Jane (Peta Jane). She was widowed shortly after and cut all references to her late husband from her life. She didn't remarry and died in 2014 having cut the Australian siblings out of her life too. Apparently, this was over a perceived slight to Jane on a visit to Sydney with her boyfriend, Keith. I remember Jane being perfectly pleasant and welcome at the time.

Cousin Jane - Christmas at Beecroft - Christmas 1987

They could certainly have stayed at my house in inner city Paddington. A far more removed Danish cousin and her boyfriend did. But apparently Jane's uncles and their wives were expected to provide superior accommodation out in the suburbs and didn't. Brenda subsequently visited Joan in Newcastle and was very welcome. The problem was with the older generation.

Early in my life I had some experience with assertive nurses. In the early 1950's my father was in and out of the Repatriation Hospital at Concord in Sydney, from which he emerged after his penultimate operation with an 'iron' back brace, a heavy bar of spinally curved steel with a waist girdle and other straps, clad in brown leather. It might not have been heavy on him but to a little boy of five or six it was an awesome and almost unmovable thing. My father hated it and soon refused to wear it, saying that it would cause dependence.

Nevertheless, he did become dependent on a bewildering array of pills - and at one stage on Benzedrine inhalers that he bought by the dozen. Both my parents also smoked imported un-filtered Kensitas cigarettes that were purchased on a regular order by the carton. They smoked heavily, a packet or more a day each, well into their sixties, when their first smoking related heart and peripheral vascular problems began. Then they both gave up - cold turkey.

Kensitas - The butler on the packet has a tiny packet on his tray.

My father told me that that packet has the same image on it; and so on; into infinity.

I loved that idea.

Stephen was fascinated by any new technology and materials, ceramic magnets, sintered bearings, polytetrafluoroethylene.

When the first transistors became available in England but not in Australia, he had my grandmother bring a bag of them in, together with a smuggled LP record of My Fair Lady, then unavailable in Australia due to licensing and copyright restrictions prior to the show being staged. The transistors went into some experimental circuits and were quickly superseded. I still have the record.

Naturally we always had an excellent Hi-Fi setup. In the 1950's this was still mono (single channel not stereo) with a 12-inch speaker in a giant folded tuned base enclosure cleverly concealed within a mobile cocktail cabinet that was made as a 'foreign order' in the factory Stephen was then managing. There was obviously a cross-over to a midrange and tweeter. The audio was based on the famous Mullard 5 valve 10-watt amplifier design and the radio tuner was Stephen's design. They were home assembled on a novel vertical chassis and the turntable disappeared or rose magically into a separate side console that sat next to his chair, while still playing. He loved special effects records that could rattle the windows. But mostly he played romantic classical music: Tchaikovsky, Mahler, Brahms, Rachmaninov and so on.

It was before TV and we listened to radio most of the time. Stephen and Vera also went to the cinema frequently usually on Saturday night and we would have a baby sitter. This also influenced the records they bought. When Drive-In theatres arrived, we would go as a family, our parents canoodling in the front seat, us annoying each other in the enormous back, eating fish and chips and drinking milkshakes.

After the Hudson we got a 1950 Packard, still second-hand but now maintained by the authorised agents Pendlebury in Parramatta. It had come to Australia for Princess Elizabeth's aborted 1952 visit when her father died. It was a beautiful car that ran almost silently, like a Rolls Royce.

Ours was pale blue I have a photo somewhere - meanwhile this is a similar car

Stephen had the Packard for some years until the mid-1960's when they could afford to buy new cars. Then he had a couple of Chrysler Valiant's followed by several V8 Holden Statesmans (men?).

Stephen also had a strong interest in Astronomy. He transformed a disc of raw Pyrex into a high precision optical mirror which he built into a 6-inch Newtonian telescope - a huge grey tube ten feet long on a wheeled mount. For quite a while it stood in the corner of our lounge-room. It was eventually made redundant by Sydney smog and street-lights. Peter still has it on his farm in the country. Stephen spent a lot of time photographing and painting the Moon, speculating on the dark side, long before the first Russian spacecraft or American space crew photographed it from behind.

He liked painting in oils. He painted my mother, fully clothed and wearing make-up, for the Women's Weekly art competition, winning a minor prize: a large signed print of a painting of trees in a country setting with purple hills by the famous indigenous artist Albert Namatjira that remained in the Family Room over the stairs for many years.

Looking at this photo now I'm not sure how it won a prize

He also painted more realistic nudes that were hung at home - to the embarrassment of my cousins. After the prize he had a local reputation as an artist and a few minor commissions. He was also invited to judge at some local fêtes and so on.

In Canada and then England he had been a keen photographer and between 1946 and 1948 when we left England maintained a photographic studio and fully equipped darkroom. To supplement their income, they let a room to a friend and he made photographic portraits of numerous people. He also made some nude studies of my mother that stood on her dressing table throughout their marriage. My mother destroyed them the week Stephen died.

Around 1960 Stephen was asked if he could assist a couple of importers of domestic appliances that wanted to bring in products were potentially unsafe and needed to meet Australian standards. He worked with the Japanese manufacturers to make inexpensive modifications and improvements much to their delight 'McKie San'. He soon realised that it was earning more per hour than in his regular job. So, in 1962 he left AEI to formally establish a consultancy: redesigning appliances and equipment to improve manufacturability and to meet Australian safety Standards and Specifications, particularly in the electric and electronic industries. Vera was his first secretary and assistant until the business took hold.

He was soon nominated as an industry member on various relevant Standards Committees and took the work very seriously. He said their task was not to protect the normal user, or even a fool, but to protect the dammed fools from themselves. 'Damn' was about as strong a word as he allowed himself.

Work showered in, not just from the Japanese but from Germany and Italy and the US. Can you imagine a commercial dohnut maker, actually working with boiling fat, in the middle of your living room or a huge early microwave oven, with a giant electromagnet, instead of today's compact ceramic magnet and magnetron?

In the middle of this period, I turned 21 years old and Vera saw it as an opportunity to display a bit of their growing prosperity. A reception place was booked and formal invitations printed. I had virtually nothing to do with it. It was not the sort of party that some of my university friends might have expected in the way of the 1960's - dark lights, loud music and people smashed out of their brains. But it turned out to be good fun with everyone in formal clothes, being very mature and grown-up.

The McKie Family in 1966

Peter, Pamela, Stephen, Sheila, Richard, Vera, Joyce, Jim

Very soon we were able to have a showroom-new car and then a second. Not long after, we moved into a new, much larger, house at 19 Lyndon Way Beecroft, with three garages into which we could actually fit three of our four cars plus a couple of spare engines peter had accumulated.

I'll drink to that...

But for Peter and me this would not last long. We were about to move out and begin our own, independent, lives.

Stephen and Vera continued to build the business with international companies wanting to market their products in Australia. The Japanese were still prominent but I was able to get an Italian client's washing machine and dishwasher for my home at rock-bottom prices and another Italian client's first-rate sewing machine that I had to reassemble after testing, that I hope my daughter still has. Julia?

Soon after we moved to Beecroft Stephen met Hans Schmidt-Harms who engaged him for some domestic product development. The Schmidt-Harms family came to dinner and there was a certain tension along the lines of the famous Faulty Towers episode - Don't mention the War. Hans had been a fighter pilot in the Luftwaffe. The tension was broken when they both refused the carrots. It transpired that they had both declared that if they ever got out of this alive, they would never eat another carrot. Great hilarity and relief. They became firm friends.

Other dinner guests included a number of Japanese clients. Some years earlier Vera had taken up Ikebana, Japanese flower arranging, and regularly won prizes in competitions. To this she added Japanese food preparation. We all brushed up our chopstick skills, Japanese chopsticks are much finer than the more usual ones they provide in Chinese restaurants. We soon acquired a taste for raw fish, raw egg and wasabi, at least as an Entrée. The Main was usually more Australian, we weren't trying to be Japanese. Japanese are so innately polite that it was hard to tell if this acknowledgement of their culture was appreciated but we all gained new appreciations and skills.

Like many Engineers, Lawyers and other professionals of his day Stephen hadn't attended a university. He was a professionally qualified engineer by virtue of his apprenticeship and a thesis on high voltage insulation and being accepted as a Senior Member of the Institution of Radio and Electronics Engineers, Australia (IREE), and a founder member of the Medical Electronics Society that the IREE subsequently absorbed. The IREE was subsequently absorbed, in turn, into the Institution of Engineers.