The Truth

Merely corroborative detail, intended to give artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative. [81]

A lot of this essay is directly or indirectly about truth. I have talked about knowledge and what we can know and I pointed out that we rely on others for almost everything we believe.

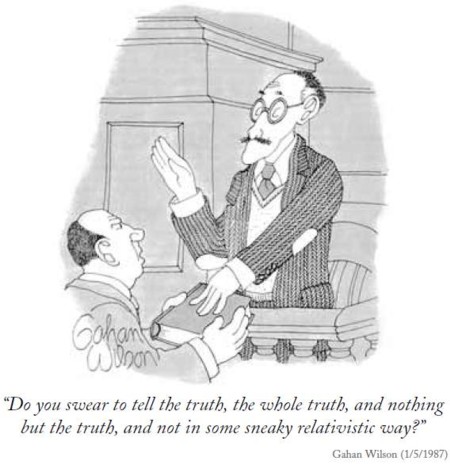

Society would not work very well if people had no regard for the truth. But what is the truth?

One of the problems for understanding truth is the way we bundle events and actions in our direct experience with cultural insights (like stories or parables that seem to reveal a truth) and with scientific hypotheses (contingent facts).

Telling the truth often involves reporting actions or other events honestly; 'who stole the tarts?' I could be untruthful in a number of ways. I may have stolen them and deny it. I may have seen them stolen by someone but deny it or I could claim to have seen the tarts stolen by someone when I did not. But it is also possible that I honestly thought I saw the Knave of Hearts steel them when it was someone else, or it was not the tarts that I saw taken but a tea cake.

Our experience is subjective. If I am blind or psychotic I might perceive the same events quite differently. My truth may not be your truth.

It gets even more complicated when I am retelling someone else's report of the theft of some tarts. Not only might I make mistakes in the detail but I might feel the need to add my own interpretations or to make the story more interesting. People feel freer to lie in these circumstances, because it is much easier to do without being caught and being called a liar. A special case is reporting our own memories of some event in the past.

I discuss scientific hypotheses at length elsewhere. Truth in a cultural context is altogether a different matter.

People often lie or don't tell the truth. In many cultural situations we demand or prefer not to hear the truth. We understand that telling the truth is not always socially acceptable or wise behaviour. To tell a host, or an employer, that: 'I think you're really ugly and smell terrible', would be very impolite and/or very foolish.

It seems that the more you can be described as intelligent (are good at tests of reasoning or are able to influence others), the better you are able to play with the truth without being detected or others objecting. People interpret the truth and select 'facts' to suit themselves. I am doing this right now.

Truth often has to be seen in context. Sometimes you are expected to lie and sometimes you will be punished if you are caught lying. I have already said that we admire people who are honest and you should try to be honest. Perhaps this means that you should be able to discover the truth and to use it wisely.

In a law court, skilled practitioners (lawyers or expert witnesses) are all but useless at reaching the truth because they are experts at persuasion and know how to select and present facts to support their case.

A large part of this skill is making opponents reveal facts that they want to keep secret while withholding facts damaging to their own case. Having ascertained which facts they are working with:

'I said the sparrow, with my bow and arrow, I killed Cock Robin',

Lawyers put these facts into cultural context by arguing about ethics and the letter of the law. Was the confession extracted unlawfully? Was it accidental? Was it self-defence? Was it justifiable for some other reason? Is it unlawful to kill robins anyway?

We often find that fiction seems to tell us more than a 'true story' but when someone is telling a story they made up we expect them to let us know it is fiction. They don't have to put a warning label on their work; they expect us to understand the clues they give us. We learn to understand hundreds of these clues; like setting the story in the present or the future, presenting the story from a character's viewpoint or including obviously fictional or fantastic elements. We get particularly upset if they try to make us think it is a true story when it is not.

As we grow up we learn the signals that tell us when someone is making up a story or flattering us or lying in some more direct way. We also learn how to detect when they are leaving out something important. These signals include body language as well as what they say or do.

We also learn how to deceive others the same way and how to be polite. We learn how to play an elaborate game in which each understands the other is not telling the whole truth and guesses what is not being said. We call that being diplomatic.

We learn to collect and use information that builds the patterns (view of the world) that help us to realise that others have been deceived or believe something that is false. For example, different religions believe contradictory things; even if one of them is right, a great many people must believe things that are false. Most important, we need to learn how to relate to those who do not believe what we do.