Culture

Culture is the name for what people are interested in, their thoughts, their models, the books they read and the speeches they hear, their table-talk, gossip, controversies, historical sense and scientific training, the values they appreciate, the quality of life they admire. All communities have a culture. It is the climate of their civilization.[55]

The word 'culture' describes how we relate to others in our society of generally like-minded people and the people who live in our community with us. It is not a very exact idea because sometimes it embraces one group and sometimes another. For many, to be 'cultured' is to understand the rules of etiquette, manners and decorum; to be able to move in polite society.

Aboriginal people often use the word 'tradition'; as in, 'in my tradition we are the custodians of the land, not its owners'.

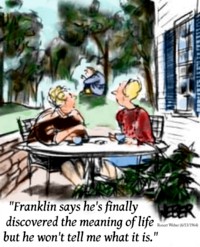

For many people our culture gives us a reason to live. The greatest part of our most influential books, films and ideas are concerned with the meaning of life, a reason for living or ways of living. In his movie 'Manhattan', Woody Allen asks, 'why is life worth living?' then he tells us that for him the things that make it worthwhile include: Groucho Marx, the second movement of the 'Jupiter Symphony', Louis Armstrong's 'Potato Head Blues', Swedish Movies and so on. Unlike other animals, we humans love stories and art and music. You will find that things in our culture make life more worth living for you too.

Humans are the first animal we know of to gain self-knowledge to the level that you have it. Most apes seem to have it to some degree but no other has developed our kind of culture.

In the Bible self-knowledge was the original sin that caused God to send Adam and Eve out of the Garden of Eden. It is the source of our happiness but also of our sorrows.

It has been suggested that it was the advantage we gained from the ideas multiplying in our heads that drove our genes to evolve bigger and bigger brains. Our brain now consumes a higher proportion of our total body resources than any other animal. The size of our heads causes problems being born and threatens our biological survival.

We like to gossip. One researcher says we gossip so much that this is the real purpose of language. We invent myths. We invent and make useful things but often we just make things for the sake of it. We have evolved to communicate. We need other people for these things.

The rules for relating to others have been evolved by society and some of them by our genes (like relating to our mother and other adults when we are babies). Some have been made into laws (like not stealing) and some are general rules of behaviour in a particular society (like being polite or not eating with your mouth open). But lots are just how we relate to our friends and to others (what do you talk about? what do you like?).

Because we need others, they can make us happy or unhappy by how they act and what they say. Some people are so dependent on others that they are dominated by peer pressure to act in ways that is not in their own interest. This can be quite unhealthy.

Our culture encourages self-reliance because this is what has worked in the past to make its members most able to contribute to its survival. We admire and encourage some solitary activities like scholarship, creating art or sciences, training for sport or meditation, that have the effect of strengthening the individual and creating new ideas.

Personal skill and knowledge is a good place to look for sources of personal strength. Learning something difficult (like playing the piano) or training for sport or some kinds of job gives us personal strength and self-esteem. People with this kind of goal are likely to be less reliant on others for their happiness and sense of personal worth.

But to be happy we all need friends we can relate to. If we are unhappy: changing our friends, setting some new goals, changing our job, getting some new interests or playing some different games can help.

In our culture we often set goals: like winning a game. But that is not why we are playing. We are playing because we like playing the game; we just like it more if we can win occasionally. It is the pursuit of the activity that is our real purpose, not the goal that we set:

To Yossarian, the idea of pennants as prizes was absurd.... Like Olympic medals and tennis trophies, all they signified was that the owner had done something of no benefit to anyone more capably than everyone else.[56]

When asked why he climbed Mt Everest, Edmond Hillary said (echoing George Mallory who failed in 1921), 'Because it was there'. The top of Everest is not a particularly great place to be. Hillary climbed to it because he liked climbing mountains, not to be at the top.

If we are playing a game only to win it is not a game anymore; we have lost the purpose and it has become an obsession or a business; like the Olympics.

To make choices in life we must have free access to all relevant ideas.

Be very cautious of anyone who wants to limit your access to ideas (or anybody else's). Censorship is a tool of repression used by dictators and extreme religion (and sometimes even democratic governments) usually by demagogues claiming that they are protecting minds weaker than their own.

As a general principle, it is much less dangerous to have all ideas allowed (even racist or extreme religious views), than to have a society in which important ideas are suppressed (no matter how well intentioned).