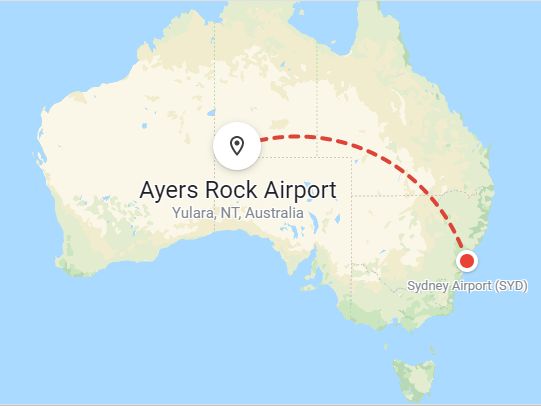

In June 2021 Wendy and I, with our friends Craig and Sonia (see: India; Taiwan; Japan; China; and several countries in South America) flew to Ayer's Rock where we hired a car for a short tour of Central Australia: Uluru - Alice Springs - Kings Canyon - back to Uluru. Around fifteen hundred kilometres - with side trips to the West MacDonnell Ranges; and so on.

As expected, the car turned out to be essential. The alternative would have been a more expensive package bus trip with all the constraints that that imposes.

The landscape

Central Australia can be daunting. Early on, several ill-equipped European explorers set out never to be seen again. This is perhaps where Central Australia got the nickname 'The Never Never'. Even today people can 'do a perish' if they breakdown off-road and have insufficient water.

This extremely ancient landscape was just as harsh when the first people arrived as it is now.

Yet people have made this environment home for tens of thousands of years (see When did people arrive in Australia? - 2017 Addendum - on this website).

George Gill Range - location of Kings Canyon - from the helicopter

The present Australian continent was once part of the landmass known as Gondwana, located at the South Pole.

Between 900 million and 300 million years ago a large depression in the Earth's crust here filled with layer upon layer of alluvial deposits: sand eroded from volcanic mountains. These sands were compressed to form sandstone layers of different density and particle size, some much more resistant to weathering than others.

Towards the end of this period the underlying crust began to disrupt the once horizontal sedimentary layers so that they tilted and deformed. In some places these became steeply sloped or vertical, forming the mountains, of which the various Central Australian prominences, the MacDonnell Ranges; Mount Conner; Uluru (Ayers Rock); and Kata Tjuta (The Olgas) are eroded remnants (see: Formation of Uluru and Kata Tjuta).

Thus, Uluru is the eroded tip of an almost vertical seam of hard arkose sandstone (the small rectangle to the right in the above graphic) that extends as much as six kilometres below the surface. A similar process formed the nearby Olgas (Kata Tjuta - the small rectangle to the left in the above graphic) although they consist of a coarser yet similarly hard-weathering sandstone. During these eons the Earth went thought cycles of glaciation and warming, eroding the ancient mountains and re-layering the valleys.

Until about 500 million years ago life on earth was single-celled, there were no multicellular plants to slow erosion and, of course, no multicellular animals to dig or trample.

The first terrestrial plants evolved from simpler organisms. The mostly nitrogen atmosphere then contained much more carbon dioxide and very little oxygen but photosynthesis in algae and then plants reversed this and during a hundred million years or so and, to cut a long story short, complex animals evolved to eat the plants; and each other.

Some of these got bigger and bigger until the age of the dinosaurs about 150 million years ago. Throughout these eons the oxygen in the atmosphere began to oxidise the many metals thrown up from the core and mantle by eruptions (except for gold that remained unoxidised). Principal among these metals was iron, of which the core mainly consists. So, with free oxygen, the Central Australian landscape went from grey, like the moon, to the red we see today, due to these iron oxides.

About 85 million years ago the continent that is now Australia, together with South America, began to separate from Antarctica and move north. This drift still continues now at a rate of about 7 cm a year and causes earthquakes and volcanoes in New Zealand where the Australian plate rubs against the pacific plate.

65 million years ago there was a mass extinction event, probably a meteor impact, when the dinosaurs, that once abounded here, together with many other animals, were all but wiped out; save for some smaller survivors like crocodiles and birds, setting the scene for the rise of the mammals, our ancestors.

About 30 million years ago Australia was fully separated from Antarctica.

At that time the planet was a lot warmer and largely ice free and sea levels were a lot higher. So, part of the new continent of Australia was below sea level and much of central Australia was under the ocean. Elsewhere great coniferous forests grew, converting carbon dioxide to oxygen, the carbon thus captured, eventually to be laid down as the rich coal deposits, now found in parts of eastern Australia.

But central Australia remained distant from the plate boundaries with their tectonic disruptions; folding; and vulcanism. As a result, almost all the landscape here consists of ancient sedimentary rocks. Some are so dense that early explorers thought them to be igneous (volcanic) or metamorphic. The underlying rocks are overtopped with the erosion products: coarse, often salty, and relatively infertile sand. Nevertheless, some plants thrive and there is a surprising variety of hardy grasses and many different and beautiful wildflowers.

Before humans evolved from earlier primates, a million or so years ago, and then some of our ancestors migrated here, perhaps 65 thousand years ago, other creatures including giant marsupials, roamed.

There is now good evidence that the first humans hunted the megafauna they found when they arrived, probably leading to their extinction (see When did people arrive in Australia? - Australian Megafauna - on this website).

Despite the preponderance of coarse grasses and scrubby trees we saw no native grazing animals. At Uluru we were told that there are no large kangaroos as it is too dry. But we saw many small lizards and lots of ants; flies; and other insects; that presumably feed the many birds, including stately raptors, like eagles and kites, like the Whistling Kite at the top of the page.

Alice Springs is noticeably more verdant than Uluru; but if Europe is a fifty The Alice is a five.

|

|

|

The Dingle Peninsular in Ireland and Alice Springs

No doubt a bit of a shock to those immigrant Irish stockmen like Clancy

We were told of larger lizards and snakes but our various, quite long, walks were on established paths. These are defined by the National Park to avoid damage to the fragile landscape, so no doubt these rather shy creatures, as did Clancy, prefer to avoid 'the ceaseless tramp of feet'.

But at Kings Canyon we did see a dingo (without a baby); some captive emus; and nearer to Alice Springs, a number of brumby horses and some wild cattle. There is also a camel farm at the Uluru (Yulara) Resort.

The winter climate took us by surprise. It rained lightly on several occasions, both at Uluru, where the setting sun created an amazing rainbow with its end right over the rock, and less spectacularly at the West MacDonnell Ranges.

Uluru Rainbow

It was cold. Daytime temperatures seldom rose above 20C. After dusk the temperature fell to half this and we were thankful for our down jackets and warm hats and gloves; still needed until the sun was well up in the morning. We were told by locals that this was unusually cold for June. In summer it's quite different. Daytime temperatures well over 30C are not unusual.

Uluru - Kata Tjuta

On our first afternoon, after a very long delay at the airport clearing the Covid-19 security checks, we picked up the car; checked in at the 'Lost Camel'; purchased our park entry passes; and set off to circumnavigate the rock in the car.

We discovered the ring road around Uluru has a gap of around a kilometre that requires a ten kilometre diversion to complete, what would otherwise be, an eleven kilometre circle.

Uluru ring road

The countryside is quite flat, particularly around the rock, but this diversion in the road runs out to the sunset viewing hillock so we stopped there with hundreds of others and waited for the magical moment.

Uluru Sunset

The following day, after a leisurely breakfast, we had a look around the resort, admiring the wildflowers.

Sturt's Desert Pea and Uluru seen from the Resort

After lunch we drove over to Kata Tjuta - once called 'The Olgas'.

Kata Tjuta - The Olgas

Here we decided to explore Walpa Gorge, advertised on line as: 'a 2.6-kilometer trail between sandstone domes with a seasonal stream & wallabies'. We saw the stream but no wallabies - probably, very sensibly, avoiding a throng of recently arrived bus tourists. But the flowers were spectacular in places and it was a good bracing, if not athletic, walk.

Kata Tjuta - The Olgas - walk

That night we had bookings for the Field of Light Experience: 'in the remote desert location with majestic views of Uluru'. The Field of Light is an art installation by English artist Bruce Munro, with, it is said (I didn't count them) more than 50,000 stems crowned with frosted-glass spheres, illuminated by solar-powered variously coloured light emitting diodes (LED's) like thousands of solar path lights. The installation opened 1 April 2016 for a limited time but became so popular with the tourist industry that it is still here.

Field of light

After watching another sunset over Uluru, complete with the serendipitous rainbow seen above, we consumed a box of canapés; and got smashed on seemingly bottomless glasses of quite good bubbly (transport, to and fro, is by coach). We were led, some of us stumbling, like an Irishman on Paddy's Day, down the hill into the maze of paths winding through the light field and challenged to find our way out the other side.

Uluru and the Field of light

No worries mate! Back in time for tea.

The following day Wendy and I set out to circumnavigate the rock, clockwise, on foot. Craig and Sonia opted for a shorter walk and then a coffee at the Cultural Centre while they waited for our return. In the end it was we who had to wait for the car to get back (no mobile phone coverage) as we had overestimated how long it would take.

Around the rugged rock the ragged rascal... walked

One has three options: walking unguided; a guided Segway tour; or to hire a bicycle. We only saw two Segway groups, both between the car parks on the southern side. In the sand they are not a lot faster than an easy jog.

A little way into our walk and Kata Tjuta - The Olgas - came into view on the horizon

That would be another good walk but - according to Google Maps - ten hours away on foot

A short stretch is quite unpleasant, along the roadside. If I was doing it again a bicycle is definitely the way to go. Yet we were only overtaken by bikes once. There were however, several small groups on bikes coming towards us, travelling anti-clockwise, and we past just one group of walkers going our way, a slow family group with small children, quite a challenge.

Nominally the circumference is about nine kilometres. Some of the track runs close to or adjacent to the face although around the back (the north side) the track runs three to four hundred metres distant. This track does not diverge into Kantju Gorge. To go to the water hole at the tip there's a half a kilometre track branching off the encircling track.

Kantju Gorge - judging by the watermark the waterhole was a bit short of full

After I diverted to Kantju Gorge, Wendy went on ahead and I caught her up quite a bit later, so for many kilometres we each walked alone. At one stage I became concerned that there was no mobile phone coverage so, for example, if my heart valve had played up there was no another soul around and only two very distant emergency medical stations (a defibrillator and emergency radio).

Further around Uluru

But everything was fine. And, although my back was black with them, there were no flies on Wendy.

There were no flies on Wendy

When we reached our starting point, my phone said I'd walked just under twelve kilometres - as I said it's flat all the way. Wendy had timed it. It took us two hours and ten minutes.

At one time it was possible to climb Ayres Rock (as it was known back then). For most of its circumference the face is sheer and this looks to be impossible without climbing ropes and pitons. But as the track rounds the western tip there's a spur running down from the top that provides a natural ramp up. This was finally closed in 2019 precipitating a rush of people getting in/up before the ban.

No climbing anymore

According to the media at the time: an estimated 37 people died on Uluru since Western tourists began climbing the site in the middle of last century, via a track so steep in parts that some scared visitors descend backward or on all fours. Some slipped on wet rock and fell to their death. Others, often unfit or elderly, suffered heart attacks from the strenuous walk and high temperatures.

Today there are numerous requests to respect the religious beliefs of the local Anangu people, who regard the rock as a sacred site. These include refraining from photographing certain features. So, watch out Google Earth.

Similar requests apply to St Paul's in London but not to Westminster Abbey, go figure. These various religious spirits are amazingly capricious when it comes to reflected, refracted or penetrating photons; yet only at certain wavelengths. I suppose that's why there was no mobile phone coverage?

Back at the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre and Museum one can buy a wide variety of cultural artefacts and a cynic (not me of course) might feel that this is all part of the creation of a tourism motivated sense of religious mystery about what is, after all, just an unusual geographic feature, that pre-dates the first humans by many tens of millions of years.

Uluru-Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre

On our third evening we were booked to have a Sounds of Silence Dinner: 'under the amazing outback sky while a story teller tells magical stories and tales'. Again, the evening began with a box of assorted canapés with copious wine, beer, and non-alcoholic drinks for those who wanted to avoid falling down. The location was out in the desert at a point not quite equidistant from Uluru and Kata Tjuta, about a quarter of an hour in the bus.

The buffet style dinner provided several courses of: 'delicious Australian delicacies'. And it wasn't too bad!

Kata Tjuta - The Olgas sunset and the Sounds of Silence Dinner

The 'magical tales' turned out to be a passing reference to Aboriginal beliefs, followed by a current astronomical dissertation by an astronomer on the age and scale of the universe, illustrated by how long those photons had been travelling before entering our eyes and thus how far into the past we were looking.

Those of us who had not been in the Cubs or Brownies; had a defective school education; or a bad memory; also learnt how to find the South Celestial Pole. There were several telescopes to look into the past with. Identified in particular was the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way. It consists of approximately 10 billion solar masses, so that it looks like a faint cloud or perhaps a puff of talcum powder, and out here was clearly visible to the naked eye. This can no longer be seen from our cities and towns, due to street lights and traffic smog:

"And the foetid air and gritty of the dusty, dirty city

... spreads its foulness over all"

It's 160,000 light-years away. Thus, we were seeing the cloud as it was 160,000 years ago, around the time when Homo-sapiens-sapiens, modern human beings, evolved from earlier humans.

As we ate, we watched Venus set and when the lights went out the Milky Way, the visible stars towards the centre of our galaxy, was spread overhead like an enormous splash of silver paint, that I remember from childhood but can no longer see from Sydney. Magical indeed!

And yet our telescopes can now see tens of billions of galaxies in the seemingly infinite space beyond. The light from the farthest has taken billions of years to reach us. Galaxy GN-z11 presently holds the record at 13.4 billion light-years from us. So, when the light our telescopes are now seeing left that galaxy, our sun and its solar system did not exist. The planet Earth would not form from a dust cloud for another nine billion years.

As many have noted when our radio and television signals, travelling at the speed of light, reach Andromeda, our nearest galactic neighbour, 2.4 million years from now, it's very likely that Homo-sapiens-sapiens will have been extinct for hundreds of thousands of years. This becomes a certainty before our signals reach more distant galaxies as our planet will no longer exist.

Thus, looking up, the Earth and all our history, hopes and worries were instantly reduced to cosmic insignificance.

So, my thoughts returned, to Clancy out here droving:

"And he sees the vision splendid of the sunlit plains extended,

And at night the wondrous glory of the everlasting stars."

Again, we were bussed back - no need for a designated driver.

Alice Springs

It's a long drive from Uluru to the Alice, 450 kilometres with just one little township on the way.

After an hour or so one comes across the Mount Conner Lookout and toilet stop. We were unprepared for the sight of this mountain that is a classic example of an inselberg, a small mountain left isolated on an otherwise eroded plain. In this case it is a remnant of a once higher sedimentary layer standing 300 metres above the surrounding plain.

Mount Conner

Wendy and I shared the drive after I stopped on the way for lunch at the Erldunda Roadhouse, where we got to see some captive emus.

The road is excellent and the car could be set to cruise, generally at 110 kph but up to 130 for part of the way. Oncoming traffic was light so the occasional slower caravan or campervan didn't delay us very much.

Erldunda Roadhouse emu and a burger for lunch (beef not emu)

Then on the road again - the Stuart Highway- and now I could use my camera

As we neared our destination the MacDonnell Ranges could be seen on the western horizon.

MacDonnell Ranges

Reaching Alice Springs, we didn't know what to expect as several friends had given the town a bad rap. So, our impressions were favourable. The town looked prosperous and business-like and the much-vaunted social problems didn't seem very evident. The trusty TomTom delivered us to our hotel.

As we were able to cook meals we visited the Woolworths Supermarket, downtown, and found it to be very similar to those back in Sydney - or anywhere in Australia.

Alice is a university town, a major medical centre and the second largest city in the Northern Territory. The population is around 25,500, making it the 55th Australian city in size, by population. Yet that's two thousand smaller than Mosman Municipality, one of Sydney's smaller local government areas.

The first task was to go shopping: some bubbly and a good red at the top of the list.

The main sign that there were problems with drunkenness were restrictions on the sale of alcohol. There is a police presence outside every retailer of alcohol, checking identities and the intended place of consumption. Yet this was not necessarily based on ethnicity as there were, obviously indigenous, customers who had apparently satisfied the entry criteria.

There are a number of tourist attractions in town and first up was the excellent Natural History Museum, at which one can learn about the geology, plants and fauna of the region as they evolved to those we see today. There was also a very informative historical photographic exhibition detailing early European settlement and their interactions with the indigenous peoples. For copyright reasons no photographs were allowed.

Another point of interest is the Alice Springs Botanic Gardens, developed by a Miss Pink - unlike any botanic gardens I've ever been to elsewhere.

Alice Springs Botanic Gardens - native shrubs; flowers; and grasses - not exactly lush

The Old Alice Springs Gaol - now also houses the Women's Museum of Australia. Here there is an exhibition celebrating Australian women pioneers in many fields particularly in aviation, very important to Central Australia.

Old Alice Springs Gaol (with prisoner cell art) - and the Women's Museum of Australia.

The Royal Flying Doctor service also has a museum featuring mainly audio-video presentations but there are some early pedal-radios and virtual reality headsets that share the experience of flying in the co-pilot's seat and caring for a patient suffering heart failure. All very interesting.

Yet the principal tourist attraction on the entire trip, from my point of view, is the Alice Springs Telegraph Station Historical Reserve.

Alice Springs Telegraph Station - The first of a number of substantial colonial buildings

due to remoteness constructed of local materials - originally with thatched roofs

Although multi-wire telegraphy had been used along railway lines in England since the 1830's it was not until the single wire system employing 'Morse Code', invented by Samuel Morse, was developed in the 1840's that long distances could be covered economically. The wire provided one conductor while the Earth provided the return path to complete the circuit.

Such was the utility of the new technology that by 1855 telegraph lines already reached Java in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) via Malaya and India and an undersea cable was proposed as far as Darwin.

In Australia, Melbourne and Adelaide were connected in 1858 and in the following year Melbourne was connected to Sydney.

The only remaining problem was how to traverse the unexplored continent. Victoria and South Australia offered prizes for the first explorers to find a route. In 1861 the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition ended in tragedy. They got as far as the Gulf of Carpentaria but on the way home the final stragglers became ill and died, possibly due to consuming improperly prepared 'bush tucker'.

The South Australian's candidate had acquired more skills and knowledge and managed a lot better. On his sixth attempt, in 1862, John McDouall Stuart at last found an overland route to Darwin; and in 1865 the South Australian Parliament approved construction of the telegraph line. Today's Stuart Highway closely follows his path.

Building the telegraph line was a huge undertaking requiring a pole every 80 metres for 3,200 km (2,000 miles) across this previously unexplored, by non-indigenous people, inhospitable territory.

Young William Whitfield Mills, then aged 27, was employed to survey part of the route and when his party found a gap in the McDonnell Ranges, through which the telegraph line could be run, they came upon the Todd River. It had recently rained so there was water at this normally dry spot. So, he named the river after his boss, the South Australian Superintendent of Telegraphs, Charles Todd, and the 'springs' after his boss's wife: Alice. Thus, one of the principal repeater stations was built here and took the name 'Alice Springs'.

Alice Spring Marker

Mills wrote in his diary that upon discovering the dry riverbed they followed it down to find:

'numerous waterholes and springs, the principal of which is the Alice Spring which I had the honour of naming after Mrs Todd'.

With unrelenting desert in the south and centre and tropical swamps in the north, for a time, it seemed that the builders had bitten off more than they could chew. Yet the line opened just seven months behind schedule on Thursday, 22 August 1872. Todd sent the first message:

| WE HAVE THIS DAY, WITHIN TWO YEARS, COMPLETED A LINE OF COMMUNICATIONS TWO THOUSAND MILES LONG THROUGH THE VERY CENTRE OF AUSTRALIA, UNTIL A FEW YEARS AGO A TERRA INCOGNITA BELIEVED TO BE A DESERT +++ |

Historic Engineering Marker

Initially the repeater stations operated like the old semaphore repeaters, like the one that used to be at Pennant Hills, between Sydney Town and Parramatta. The message was received by an operator, recorded manually, and then resent on its way. Obviously, this was both time consuming and prone to accumulating errors at each of the eleven Australian stages, and many more stages to London.

This potential for corruption is well known to those who've played the party game: 'Chinese Whispers'. For example, if great care is not taken not to add or delete the word 'NOT' (dash dot; dash dash dash; dot), the message conveys the opposite of that intended.

Information theory says that errors, known as noise, can never be entirely eliminated. The telegraph was inherently noisy. When wires are suspended on poles, natural phenomena, such as lightning, can easily obscure parts of the message or add two dots where a dash should be, perhaps turning 'NOT' into 'SOT', thus requiring clarification. The experience gained, as a result of early telegraphy, was invaluable in our progress towards modern communications.

Today, digital communications employ a check-bit on every byte and a check-sum on every data packet transmitted over a network, so that any packet failing to match its sum, due to missing, reversed, or extra bits, is disregarded and automatically re-sent until verified. This is one of the principal reasons for transitioning networks; and many other systems, such as graphics; from analogue to digital in the late 20th century.

In the beginning a message to London took four days; directly and indirectly requiring many person-hours of transcribing and resending; and it cost a small fortune. Yet the psychological impact on Australia's sense of isolation was profound. Four days was a huge advance on a letter that might arrive in two months; with the reply requiring another two months.

There was considerable and expensive on-going maintenance repairing the wires some 30,000 iron poles and many more thousands of timber poles. The more remote stations like Alice Springs and Tennant Creek required a permanent staff to maintain the batteries and relay messages.

Staffing and resupply overheads were substantial

Everything had to be brought in by camel trains managed by 'Afghans'

Actually, mainly from what is now Pakistan - then northern India

The train when it finally arrived was called 'The Ghan' in tribute and many ancestors remain in the Alice today

The batteries consumed significant tonnages of chemicals and maintaining them took up a lot of the men's time.

Maintenance overheads

In the interests of robustness and cost the first wire used was of galvanised iron imported from England. But the electrical conductivity of this metal is relatively poor requiring repeater stations every 250 km with an EMF of 220 volts - about as high as one can go without killing the occasional operator. Lightening was another serious hazard to the operators and a lightening conductor was installed on every second pole.

The undersea cable to which it was connected was a single wire of brass sheathed galvanised copper, enabling much longer runs without a repeater. So, it was soon decided to upgrade the wire to copper enabling the removal of many intermediate repeater stations.

The technology improved steadily. Soon it was possible to punch a paper tape and then resend the received message without re-keying it. Soon improved undersea cables connected other parts of Australia.

The single wire system employing 'Morse Code'

and paper tape technology foreshadowing the 20th century Telex

So, in just a few years after the first European explorers: the route had been surveyed and mapped, with considerable accuracy; a two-thousand-mile-long telegraph line had been constructed, complete with supply lines to eleven repeater stations along its length; and the South Australian Government had begun to encourage pastoralists to take up vast properties to grow cattle - cattle stations. Opening the country was an even greater priority for some and the first pastoral leases in the Alice Springs region were granted even before the telegraph line was completed.

Soon the small town of Stuart, about three kilometres south of the telegraph station on the Todd River, was founded. The first growth spurt was when alluvial gold was discovered nearby in 1887, bringing in fossickers. But it wasn't until 1929, when the train line from Adelaide was built, following the route of the telegraph line, that Stuart's non-Aboriginal population began to grow.

Yet the telegraph station remained the principal communications hub and confusion with the Stuart rail terminus resulted in the town's name being changed to Alice Springs in 1933. There was another population surge during WW2 when the rail terminus became an important military staging point, in support of Darwin that had come under attack from the Japanese.

In 2004 Alice Springs was connected to Darwin by rail, completing the link from Adelaide. Contrary to expectation, since that time the population of Alice Springs has declined.

Running through town is the almost permanently dry Todd River the deep sands of which create a challenge for the many legged 'boats' of the annual Henley on Todd Regatta.

Site of the Henley on Todd Regatta

Due to Covid-19 'The Regatta' was cancelled this year for the second time only. The first time was when the river, uncooperatively, had water in it.

We felt the need to see some running water and drove out to Simpsons Gap in the West MacDonnell Ranges.

Simpsons Gap

After three days we considered that we'd had a good look around. No doubt there are other things to see and do but they will have to wait for another time.

The following morning, we set out for Kings Canyon 322 kilometres away.

Hermannsburg Mission

We stopped at the old Hermannsburg Mission for lunch. It was freezing and we had to get out the big coats and warm hats.

Just five years after the opening of the Overland Telegraph Line Christian Missionaries headed out in search of new souls to save. There was already a Lutheran community at Bethany in the Barossa Valley in South Australia. Two missionaries Hermann Kempe and Wilhelm Schwarz set out from there arriving here on the Finke River with: 37 horses; 20 cattle; about 2000 sheep; five dogs; and some chickens. By the end of 1877 they had constructed dwellings, stockyard and a kitchen and they had been joined by their wives and another missionary and three lay workers.

Five more buildings and the Church followed.

Hermannsburg Mission

They named their Mission after Hermannsburg in Germany where they had trained. They then set about converting 'the heathen'. To facilitate this the missionaries learnt and documented the local Arrernte language, developing a 54-page dictionary of 1750 words which was published in 1890. In this they emulated other Christian ministries around Australia so that today several Aboriginal languages have been restored using these valuable documents.

Teaching in Arrarnta and English or perhaps, at one stage, German

It was not easy going. Local people became dependent on the food that was traded in return for their children attending classes and a series of droughts led to cattle being taken and to the illness and death of several of the Mission staff.

The impact on the local people is discussed in more detail above in the section on Aboriginal Culture below.

This land was handed into to traditional ownership in 1982 under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976, and the area is now a museum and is heritage-listed.

Soon after leaving we hit the unmade road.

Paddy melon (Cucumis myriocarpus) - It was growing all along the side of the road

Apparently some brightspark introduced it to feed their camels, it's now a weed in Central Australia

We didn't know what it was at the time - but it didn't taste nice

Wendy had taken over the driving and proved her competence at handling the road you can see above: sand, dust and corrugations - and overtaking several campervans - for around 160 kilometres.

Kings Canyon

Kings Canyon Resort has a pub and a restaurant. It was still freezing and after comparing meal prices - not much different - we opted for the restaurant, which was also a shorter walk.

The next morning, we checked out the helicopter tours and were able to get a flight almost immediately. This proved to be a highlight of the trip and had the added advantage of identifying a walk into the canyon to do and another to avoid.

Kings Canyon helicopter tour

Then came the slightly harder part - exploring some of it on foot. We took the low road.

Kings Canyon walking track

At one time this was cattle country. Wild cattle were herded into the canyon to be rounded into a mob that could then be taken to market. The remains of the old yards can still be seen.

The remains of the old cattle business

The following day all that remained was the 320 kilometre drive back to Ayres Rock Airport this time on good roads.

Yet it was clear on the trusty TomTom that the distance as the crow flies is only 130 kilometres.

The huge diversion is needed to avoid Lake Amadeus, the largest salt lake in the Northern Territory, and the adjacent Lake Neale.

In 1872 the lake's expanse proved a barrier to the explorer Ernest Giles, who could see both the as yet undiscovered Uluru and Kata Tjuta but could not reach them because the dry lake bed was unable to support the weight of his horses.

And so, it was back to Sydney where it was both cold and raining.

Aboriginal Culture

Like other imposing landscapes in: the Western United States; Nepal; or Tajikistan; for example, one's personal insignificance, in both time and space, is palpable.

Little wonder that people have been overawed since our distant ancestral cousins first arrived here. Thus, the first human inhabitants, as they did everywhere, developed myths and lore that underscored their relationships to their environment. These beliefs and practices can be described in religious terms as animism a belief in spirits within the landscape often encompassing the spirits of the dead.

At a more pragmatic level these customs incorporate evolved knowledge and practice essential to human survival in this harsh environment. Among these are the 'song lines' that facilitate intergenerational remembrance of places to hunt, to find food and water and places to avoid. There is genetic evidence that over the millennia people of this region adapted to the harsh environment.

A 2016 study identified unique morphological and physiological adaptations, in Aboriginal Australians living in the desert areas enabling desert groups to withstand sub-zero night temperatures without showing the increase in metabolic rates observed in Europeans under the same conditions. This is an example of gene–culture coevolution, the sociobiological observation that because of the importance of culture and complex social organization to human evolutionary success, genetic and cultural development go hand in hand. In this case it appears that both genes and culture have simultaneously adapted to survival in a very harsh environment (see Gene–culture coevolution and the nature of human sociality - Transactions of the Royal Society of London; and When did people arrive in Australia? - 2017 Addendum - on this website). Thus, interfering with either the culture or the genes could be expected to have an adverse effect on survivability, should people wish to continue to live here, as their ancestors did for thousands of years, before external interference.

At one time these pre-Christian 'heathen' beliefs were considered by Christian Europeans to be anathema and their continued practice by 'the heathen' to deny the 'savages' entry to the putative 'Kingdom of God'. Missionaries gathered financial support from fellow believers and came here to convert the people; and thus, to save their imagined: 'immortal souls'.

Today this is seen by many Australians to be a form of cultural genocide and Aboriginal beliefs are now, generally, respected here as might be those equally valued, but perhaps less practical, beliefs practiced by the inhabitants of Vatican City.

Actually, the missionaries here were predominantly Lutheran so rosary beads; images of the Saints and the Virgin; and Gregorian chants; didn't supplant the Aboriginal equivalents that now bring an income; and sometimes fame; to indigenous artists and performers.

At the old Hermannsburg Mission the clash of cultures is most evident in a rather schizophrenic museum: at one moment glorifying the men and women of God who sacrificed so much in the pursuit of their mission; while at the same time not shying away from the great harm that they, perhaps inadvertently, did.

But then they were not alone in this destruction of an ancient culture. European fossickers and drovers like Clancy came here without female companionship and the inevitable mixed-race babies resulted. Well-meaning religious charities provided education. Then in 1905 the State, Territory and Federal Governments, reacting to stories of 'half-cast' children being killed by tribal elders, decided that these children required special protection. So, they were removed from their mothers, sometimes by force, and sent places like Hermannsburg Mission to be taught English and how to be a stockman or kitchen maid. Some were put out for adoption and encouraged to mingle in a belief that aboriginality would soon be 'bred-out' in 'White Australia', through a policy of assimilation.

In my State, NSW, this practice was discussed as a positive good in Social Studies at Thornleigh Primary School and it continued until 1967 (see: The Stolen Generations: The removal of Aboriginal children in New South Wales 1883 to 1969). I was by then an adult and a voter. I didn't know nor had I met a single person identifying as Aboriginal, although, thinking back, some of the children I played with at that very Primary School could probably have claimed Aboriginality. So I have to confess to harbouring some ambiguity as to the merits of the policy and thus, perhaps, to shared culpability for the harmful outcomes.

In 1997 the 'Bringing Them Home' report highlighted the harms suffered by the 'Stolen Generation' and recommended Australian parliaments offer an official apology. Many politicians resisted but on 13 February 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd gave the, long awaited, apology.

One outcome of the resulting blending of genes and culture is that Aboriginality is no longer based on racial characteristics such as skin hair or eye colour or the shape of one's face or stature. Many Aboriginal Australians resemble Europeans. There is no accepted genetic test. Aboriginal people define Aboriginality not by skin colour but by relationships. Light-skinned Aboriginal people often face challenges on their Aboriginal identity because of stereotyping (see: Aboriginal Identity: Who is 'Aboriginal'?).

At the Uluru (Yulara) Resort almost all the staff appear to be Aboriginal and, with the small exceptions, that one would find in any large business, they were professional, competent and pleasant to deal with.

For more on this subject go to: When did people arrive in Australia?- The oldest Culture on Earth - on this website.

Our accommodation

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic booking accommodation at Uluru was problematic on two grounds. The indigenous population is believed to be particularly vulnerable so that any evidence of community transmission is sufficient to close the Territory border. And because Australians, who love to travel overseas, have been kept home most Australian tourist resorts are fully booked months ahead.

The only accommodation available at Yulara (Ayres Rock Resort) was at the comfortable, three-star, 'Lost Camel'. Bizarrely, all the windows are frosted - even in those rooms with a potential view of the swimming pool or the surrounding countryside. Otherwise, the rooms are quite large with a sitting area and well-appointed with large comfortable beds; good linen; good showers with all the usual little bottles and soaps; a small fridge; and tea/coffee making.

Yulara (Ayres Rock Resort) - hotels in the distance

At Alice Springs we booked two apartments at an apartment hotel, each with a sitting room and kitchenette complete with washing machine (for clothes).

Alice on Todd Apartments

At the Kings Canyon Resort, where there is little choice, as it is all one establishment, we booked two 'luxury' cabins that were conveniently close to the restaurant - facilitating big breakfasts and two, enjoyable, well-oiled evening meals - extending until throw-out time.

The Photo Album

To see the album click on the image above