Gabriel García Márquez's novel Love in the Time of Cholera lies abandoned on my bookshelf. I lost patience with his mysticism - or maybe it was One Hundred Years of Solitude that drove me bananas? Yet like Albert Camus' The Plague it's a title that seems fit for the times. In some ways writing anything just now feels like a similar undertaking.

My next travel diary on this website was to have been about the wonders of Cruising - expanding on my photo diary of our recent trip to Papua New Guinea.

Cruising to PNG - click on the image to see more

Somehow that project now seems a little like advocating passing time with that entertaining game: Russian Roulette. A trip on Corona Cruise Lines perhaps?

In the meantime I've been drawn into several Facebook discussions about the 1918-20 Spanish Influenza pandemic.

After a little consideration I've concluded that it's a bad time to be a National or State leader as they will soon be forced to make the unenviable choice between the Scylla and Charybdis that I end this essay with.

On a brighter note, I've discovered that the economy can be expected to bounce back invigorated. We have all heard of the Roaring Twenties.

So the cruise industry, can take heart, because the most remarkable thing about Spanish Influenza pandemic was just how quickly people got over it after it passed.

The history books tell us that the Roaring Twenties were a reaction to the end of the Great War. Yet the War was but one of the hurdles that had to be overcome. The Spanish Influenza pandemic was, more briefly, an enormous burden on post-war society - shutting down commerce, in the same way we are now becoming familiar with, and killing tens of thousands.

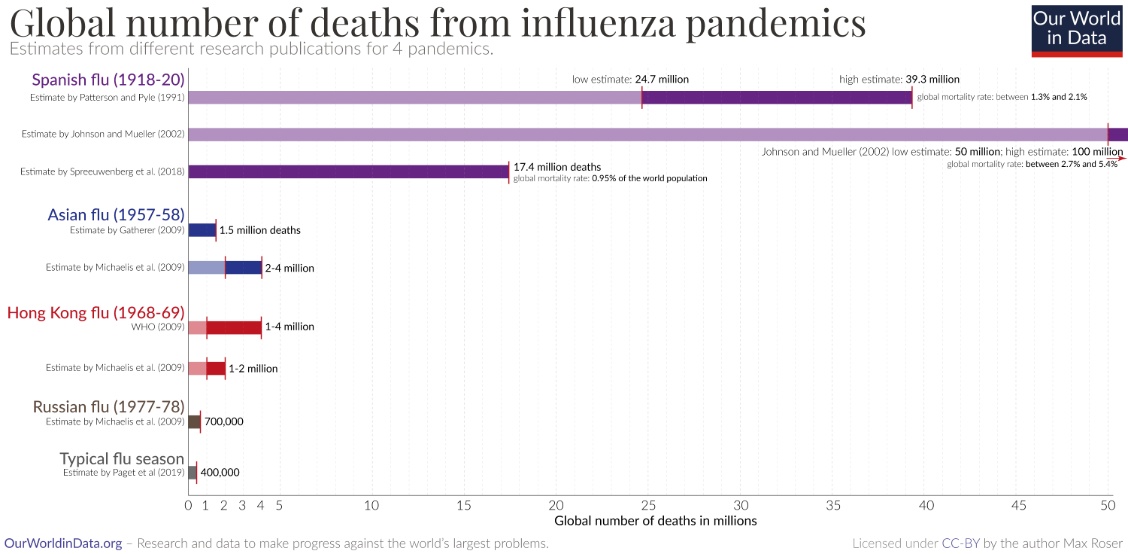

Although historians disagree over the numbers all agree that the Spanish Influenza pandemic killed a great number. The lowest estimate is 17 million worldwide while another puts it at between 24.7 and 39.3 million. Most, including the National Museum of Australia and Wikipedia, tell us that over 50 million people died worldwide. Globally this is more than died in the Great War (WW1). For example, the United States lost less that 120 thousand to the War then over half a million to the pandemic. But in Britain and Australia, where the pandemic was better managed, the wartime losses, predominantly of young men, were three to four times higher than those, more evenly spread between genders, due to the pandemic.

So in the shadow of the dreadful losses in World War I, that are memorialised in our streets and parks and still remembered reverently at least twice a year, the pandemic that took many young women too, has been almost scrubbed clean from collective memory.

There are perhaps several reasons for this social amnesia. The most obvious is that it's a bit hard to blame anyone for an act of nature and those who believe in an all-powerful, omniscient deity are reluctant to blame their God. They would rather believe that one or more supreme beings engaged in indiscriminate mass murder for some mysterious purpose, leaving the world a better place. Another is that, unlike the War, the Spanish Influenza pandemic got its killing over with quickly. Region by region, the deadly peak lasted only a few weeks and once it was over and herd immunity has kicked in, those who were left were now relatively safe and could get on with their lives without fear of an immediate recurrence. And finally those who survived were grateful or guilty or both and the generations who came after were the children of those survivors while the ones who died left few descendants and soon became a footnote.

As we are seeing repeated in Italy, Spanish Influenza killed many doctors and nurses between 1918 and 1920 but medical services were not completely overwhelmed everywhere. Our ancestors were no less competent at dealing with pandemics that we are. There had been many earlier occurrences, including The Plague. Most ports had nearby quarantine stations against just such an eventuality. Ships were carefully monitored. So the tried and proven response was to impose curfews; isolate the affected community; and in the absence of any effective cure (although many were tried) let the disease run its course to 'burn itself out', after which survivors could re-join the wider community.

But nothing had been seen on this scale for over two centuries. The Spanish Influenza turned out to be the most deadly pandemic since the last Black Death (the bubonic plague caused by a bacterium: yersinia pestis) pandemic in Europe in the 17th century.

There were a series of earlier Black Death pandemics, beginning in the 14th century when as many as 60% of the populations in affected cities died. Thereafter plague pandemics recurred regularly every couple of decades, sometimes killing up to 20% of the population, so that during the middle ages Black Death pandemics became accepted as a regular fact of life. Historians don't really know why these Plague pandemics gradually became less deadly and then stopped. The rapid and effective quarantining of outbreaks helped. Scientists have suggested the widespread introduction of sewers and better hygiene but others credit survival of the fittest. Like rats becoming Warfarin tolerant, modern humans simply became more resistant.

Spanish Influenza began in the trenches of the Great War. It affected all combatants and German losses may have helped to bring about the armistice. English speaking soldiers knew it as The Gripe and most got over it in a few days but a percentage died. Against the background of the general carnage it was kept quiet and official concerns over the new losses due to disease were censored on both sides, lest the enemy take heart.

It may have been introduced to the trenches when the Americans arrived, since it was the first H1N1 pandemic, swine flu, that is now discovered to have jumped to humans from pigs, that got it from, still unidentified, waterbirds. Perhaps it jumped to one of those Doughboys from down on the farm, before he saw Paris?

From the trenches it soon spread across Europe and arrived in relatively peaceful Spain where it spread exponentially through the civilian population and soon infected the Royal Family. Soon the hospitals were overwhelmed with the dying and its new name was sealed. But as the war ended and the troops returned home the 'Spanish Influenza' began to appear across the world.

Australia had prior warning. At the time it still took several weeks to get to Australia from Europe and travel restrictions and quarantine were immediately imposed. Initially these worked well and while much of the rest of the world saw millions fall ill and tens of thousands die in 1918 Australia still looked on in isolated horror, particularly at the deaths in the Mother Country where 228,000 died. Then in 1919 returning troops, desperate to get home to their families, broke quarantine in Melbourne and people started to fall ill in Victoria. The newly federated states closed their borders but it was too late. Amidst the interstate blame-game, public meeting places were closed; gatherings were banned; people started wearing masks; and temporary hospitals were established. The newly established Commonwealth Serum Laboratories began working on a vaccine.

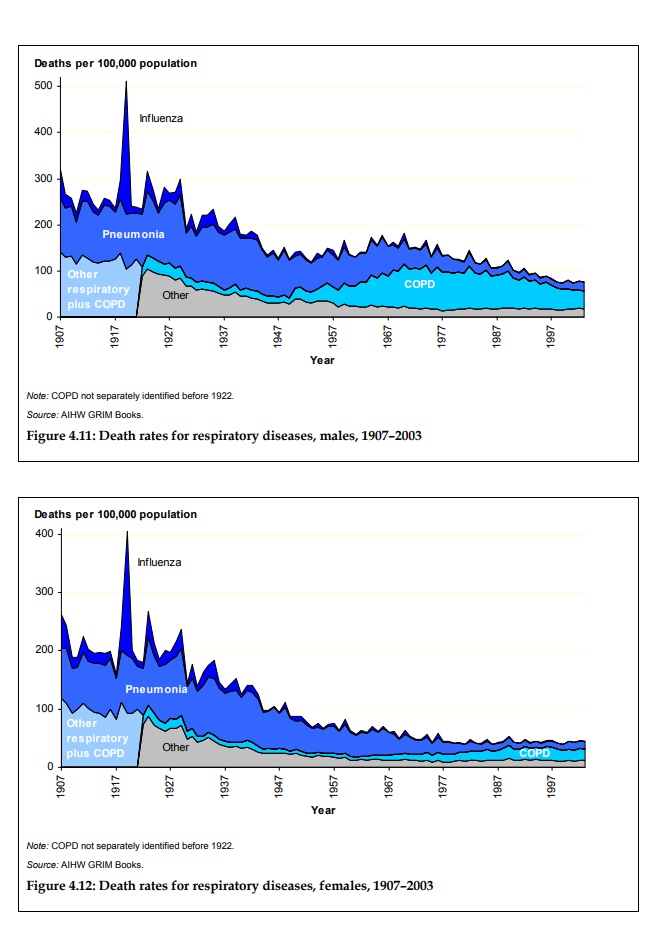

Yet within a few months an estimated 15,000 Australians died of Influenza, over and above those who could have been expected to die due to other causes, when Australia's total population was 5.3 million.

from: Mortality over the twentieth century in Australia - Trends and patterns in major causes of death

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare - 2006

According to Wikipedia: 'a 2007 analysis of medical journals from the period of the pandemic found that the viral infection was no more aggressive than previous influenza strains'... yet 'it was particularly deadly because it triggered a 'cytokine storm', which ravages the stronger immune system of young adults' and it was a new virus type to which there was no residual immunity.

There was also a problem with the early vaccines. Doctors and scientists had imperfect knowledge of viruses or their function. The first vaccine was discovered serendipitously when Cowpox was observed to confer immunity to Smallpox. Hence the name, after vacca - Latin for cow. Early vaccines were largely based on trial and error. Some worked and others didn't and they really didn't know why.

From the late nineteenth century it was realised that communicable disease was the result of 'germs' rather than vapours (miasma) or the demonic possession of the middle ages, when a priest might be called instead of a physician, usually with much the same outcome. Even malaria was discovered to be caused by a parasite and not bad(mal)-air. Bacteria and other such microscopic parasites: 'germs' were found to come in a wide range of sizes and many more became identified as microscopes improved in the late nineteenth century. A common example was the e-coli gut bacterium that's about 6 micrometres long and requires a magnification of 1000 or better to see it clearly.

But viral diseases remained a mystery. That some 'germ' was responsible could be inferred but none could be seen. This was still the case in 1920 and on line you can still see photographs of the bacteria some thought to be responsible. The trouble was that bacteria, while microscopically small, are quite large independent cellular entities, much bigger and more complex than a virus. A typical virus particle, or virion, is spherical or ellipsoid less than 120 nanometres in diameter, less than a 50th of the size of e-coli.

Not until the invention of the electron microscope by German physicists, between the wars, was a virus first photographed in 1935. But how virions worked was still a mystery. It was not until 1955, when I was in Primary School, that Rosalind Franklin elucidated the full structure of the tobacco mosaic virus, following the discovery of the structure of DNA that her work had helped with two years earlier. Thus the role of the encapsulated RNA in its function in the replication of viruses was revealed.

A modern photograph of the H1N1 swine flu virus that caused Spanish Influenza Cybercobra at English Wikipedia / CC BY-SA

So almost all we know about viruses has been discovered in my lifetime. When I was at University electron microscopes were still exceptional machines requiring their own dedicated room in a building, comparable to the mainframe computer. Now you can pick up a second hand one, that's a lot more sophisticated than those in my day, for the price of an upmarket car. So we now know that a virion consists of nucleic acid contained within an outer shell of protein the shape and binding function of which is encoded for by the RNA or DNA payload contained within.

In order to reproduce it invades a functioning cell and captures its reproductive functions to manufacture copies of itself. The outer protein is designed, by random mutation and trial and error, to bind to vulnerable cells in animals, plants and even bacteria. Viruses are very widespread in nature where they play an important part in the evolutionary process. They have been around since life on Earth began, so most complex multi-cellular life has evolved means of dealing with them. In animals like us this is our immune system.

The knowledge we have gained by the advance of science in less than a hundred years has facilitated the production of effective and safe vaccines for a wide range of known viruses affecting humans most notably: measles; mumps; rubella; diphtheria; tetanus; pertussis and polio against which sensible parents immunise their children and themselves. In addition, most of us get immunised annually against seasonal influenza, like H1N1 and other flue types.

Suddenly this recent understanding and capability is being put to the test. As happened in 1918, we are again facing a newly evolved and particularly aggressive virus, against which we have no residual immunity.

We understand that there are presently only two ways to obtain that immunity. The first is to be infected by the virus and survive so that our body's natural defences develop to defeat it. The second is for an effective, safe vaccine to be proven, manufactured and distributed. This is presently thought to be a practical impossibility in less than a year or perhaps two. The recent Ebola vaccine took five years to distribution. A possible but unproven third solution could be to engineer or discover an effective antiviral but even if possible that is likely to take longer than a vaccine.

But not everybody needs to be immune immediately, if ever. If governments can bring the virus under strict quarantine in some areas, so that it is eliminated locally and no one else can bring it in, we go back to square one - all they have to do after that is ensure that no one with the virus remains in the isolated area and no infected person is admitted.

Yet that maybe a big ask in an entire country. It's an even bigger ask in the case of Covid-19. It seems that that there are asymptomatic carriers wandering around and that's how it got loose in the first place. To achieve total elimination authorities will need to test everyone who could possibly have come into contact with the infection and isolate any positives until well. Even then a resurgence may prove impossible to stop unless the borders are kept completely secure indefinitely. Very fast compulsory isolation of infected and possibly infected people must be in place the moment an outbreak is detected.

At the other end of the management spectrum we could simply let nature take its course. In that case, with an initial doubling every few days, there would soon be tens of thousands infected, as has happened in Lombardy in Italy and is now beginning in New York.

As it was in Spain in 1918, the consequences are overflowing hospitals and several thousands of additional patients dying for lack of resources. Yet as we have already seen in the worst hit places eventually the deathrate begins to fall as the virus is less able to find fresh fields in which to replicate. When it stops multiplying entirely 'herd immunity' will have been achieved.

An alternative, while we wait for a vaccine, is a mixed strategy in which the most vulnerable sections of the community are locked-down for the duration and the less vulnerable remainder is allowed to establish herd immunity. Under that strategy the rate of new infections would be moderated by social distancing, and so on, to 'flatten the curve' but ultimately the virus would be allowed to run until those who are infected and recover make up a significant proportion, perhaps 60-80%, of the population. It seemed that this was to be the British approach as announced by Boris Johnson two weeks ago (12th March 2020), before the deaths began to mount and the dire political consequences became more apparent.

Yet soon all leaders worldwide will need to decide between:

- to lock-down only the most vulnerable then allow nature to take its course, still with some fairly draconian social management to 'flatten the curve', thus suffering the many deaths that will inevitably occur; or

- to lock-down all but essential services, including healthy people, over 80% of whom would otherwise get mildly sick then quickly recover, until no more cases are detected, simultaneously laying waste to many livelihoods and to the economy at large, while leaving the community at large vulnerable to a new wave, as soon as an infected person from outside breaches quarantine.