For no apparent reason, the silver haired man ran from his companion, shook a tree branch, then ran back to continue their normal conversation. It was as if nothing had happened. The woman seemed to ignore his sudden departure and return.

Bruce had been stopped in peak hour traffic, in the leafy suburban street, and had noticed the couple walking towards him, engaged in good humoured argument or debate. Unless this was some bizarre fit, as it seemed, the shaken tree branch must be to illustrate some point. But what could it be?

Just as the couple passed him, the lights up ahead changed and the traffic began to move again.

The tree shaking incident now preoccupied Bruce as he drove. The man had seemed to scamper randomly. What sort of debating point could he possibly be illustrating? Something about the seasons or falling leaves? Was it was about dislodging fruit; or possums? Or maybe it was about insects; or wind; or sound; or resilience; or vitality; or virility?

Virility!

***

Bruce and Fiona have been obsessed by virility, ever since they got married. They were together for five years before they decided to start a family. Since the marriage she's stopped all contraceptive precautions but she doesn't seem to be as fertile as she might have been back then. Fiona had been taking ‘the pill’ since she was fifteen. Yet, by now, her body should have returned to normal.

Or is it his fault? At close to forty, his sperm count has dropped a little and he's not as ‘instantly enthusiastic’ as he was a couple of decades ago. The doctor says there’s nothing wrong. Everything is normal for a couple their age. But everyone is different; and doctors always try to reassure. In the doctor’s defence, Fiona did fall pregnant briefly a year ago; but quickly lost it. After their initial excitement, their hopes were cruelly dashed. Now she's ovulating again.

Bruce knows what to expect, as he pulls into his parking space. He's beginning to dread this time of month. It’s been getting worse around this time, each successive month. Urgent demands to perform, followed by hope, then tears and recriminations. Will it never happen? So he's taking his time getting home, still thinking about the strange episode he had witnessed in the street. A dreadful foreboding? And it’s getting dark.

He opens the door, drops his bag, and makes a quick trip to the bathroom. As he emerges, something is different: Fiona must, surely, be home by now; but there's no matter-of-fact demand to go straight to the bedroom.

She emerges smiling, looking beautiful in her silk evening dress. She's wearing her high heels.

"Are we going out somewhere?" he asks, worried that he's forgotten some business or social event. She smells warm and fresh. She must have showered when she got home.

But despite his tardiness she's not angry. Still smiling coquettishly, she reaches out and removes his tie. She embraces him and with a passionate kiss and slides his jacket from his shoulders. It falls untidily to the floor.

They're not going out.

Holding his hand like a child she leads him, not to the bedroom but to his chair at the table, where she lights the candles, before turning down the room lights.

They both have demanding well-paid jobs but Fiona must have left early this evening. She's obviously been home for some time and has put a lot of thought and effort into reviving his waning enthusiasm. She's made this one of her 'projects'. Their large, modern apartment is at the perfect temperature and redolent with her most expensive perfume. Romantic music is softly playing.

The table is beautifully set with fresh flowers; fresh linen; small wine glasses; and a full set of the best cutlery. It’s like his birthday. Three courses. Cold soup and desert, that she must have bought on the way home, and she's put some special touches to his favourite: lamb stew, that she'd pre-prepared, especially for this occasion.

He wants to mention the strange man but Fiona steadfastly steers their conversation to their early love affair and the places that they had enjoyed together, like that bizarre hotel in the Tasmanian wilderness where they'd watched porn on her laptop and made love repeatedly. He doesn't mind - she's achieving her goal and leaving nothing to chance, this time.

As Bruce finishes desert Fiona rises and again takes his hand, like a child. This time they are heading to the bedroom. Fiona slips out of her clothes and Bruce, enthusiastically, follows her lead. He's entirely at her command, as she directs him to her will. She looks and smells wonderful and he's spellbound.

Her intent tonight is clear: they are going to try for a baby again. But as he begins the foreplay she always enjoys; a vision comes to him of that strange man shaking the tree. Now he's sure that it was something to do with all this: reproduction.

He and Fiona have been reading several books about reproduction. He knows that, with Fiona’s earlier encouragement, he's already assembled about as many of his ‘soldiers’ as there are people in a small country.

When she embraced him, before dinner, Fiona began their mobilisation - their initial call to duty. Now they are engaged in foreplay, he is assembling his main force - each individual aware of their mission to be first to their goal: the procreant egg.

Fiona's ovum is already anticipating their arrival, slowly descending one of her fallopian tubes. He's thinking about the adequacy and compatibility of her fluids. "Damn!" The medical text has replaced the Kama Sutra in Bruce's erotic thoughts.

His initial mindless lust has dissipated. His reasoning mind's taken over again and he's thinking about the medical complexities and biology, while absentmindedly going through the motions - doing what Fiona likes most. And with years of coaching, he's become very skilled at pleasing her. She's beginning to whimper.

Despite her excitement he's thinking of medical things. Which of his ten million or so individual spermatozoa would he like to win this race? Obviously, the winner will result in either a boy or a girl. Each will be as similar, yet different, as the individuals in a single enormous family. Depending on her ova, this period, and their combined DNA, some will be tall, others short, some bright, some handicapped, some easily habituated to drugs or gambling and some good at sport or mechanical skills. Some combinations may be so faulty that the foetus will not thrive, like that recent miscarriage.

"Maybe that’s what happened last year - a faulty sperm or egg," he thinks. "But that's much better than being just mildly faulty- so that the foetus survives but the child is severely handicapped! Fiona could never cope - not with her beloved career intact."

"The odds are good. Most ova and sperm are perfectly healthy and just one combination will win. The millions of others will just die and be flushed away. No one ever considers them."

In his imagination his millions of 'troops' are all manoeuvring around, like contestants at the start of a huge marathon. Every second, a different group will jostle forward, to lead across the starting line.

As he's still trying to line up ten or twenty million different runners in his imagination, Fiona reaches a noisy climax. "The neighbours will have heard that!" he thinks. "More snide comments, when we run into them."

Two or three minutes later, Fiona recovers sufficiently to realise that something's wrong. Bruce's no longer where she's spent so much effort to get him.

And he's ashamed of his obvious loss of enthusiasm.

He's thinking: "I've lost the plot again! My mind has drifted off. And it's all due to that bloody tree shaker!"

Now Fiona's paying him her full attention.

"She knows how to make me do as she wishes," thinks Bruce, just before everything is driven from his mind; everything except her sexuality and his extreme arousal. Now, there's nothing but pleasure in his universe.

After half an hour, they roll together, without disengaging, so that he's above.

Fiona has decided to bring this evening's 'project' to its conclusion.

"Now it's time! Give me that baby," she demands.

Bruce can't refuse her. He's pushed beyond carnality's edge.

As he tumbles headlong over his imagined metaphorical cliff he cries out - like a man falling through the void.

C'est la petite mort! - it's 'the little death'.

The race, that will, at last, successfully merge two life forces to become a new, independent person, is underway.

***

A year later, Bruce is a typically proud father. His friends politely listen to his enthusiastic reports of little Ada’s latest achievement - a reached for toy. While this gives those friends and colleagues with young children an opportunity to respond with their own report, others just smile. They've seen it all before but are pleased to see him so enthusiastic. Bruce has lots of photos on his phone and, if encouraged, will even talk about assisting in the drama of the birth.

It's obvious to all the world that Ada’s unborn brothers and sisters, who might have been, are not. The little boy, a future rock star, that would have been born, but for that shaken branch, will never exist.

Fiona and Bruce have a large, bouncing, precocious, baby girl instead. No one gives another thought for Ada’s ten million potential siblings, another of whom, given fractionally different timing, might have been. Humanity's taken another direction.

Bruce and Fiona now find their lives consumed by late night feeds; changing nappies; sourcing disposable nappies (diapers); bouncers; prams; sourcing stimulating toys; expressing milk; babysitters; and getting some sleep.

***

Bruce is driving home, by his usual route, when he sees the old couple from a year ago, now walking hand-in-hand. They must live close by.

On an impulse, he pulls over, leaves his car and approaches them saying: “You don’t know me but I’ve seen you two around here before.”

Almost in unison, they quizzically and with a note of caution, say: “Hello?”

Bruce explains: “A year ago I was driving past and I saw the most peculiar thing. You sir…”

“I’m Robert” he interrupts, pleasantly.

“Robert. You and your wife?”

“Rebecca” she adds, even more charmingly.

“You and Rebecca were having some kind of animated debate when suddenly, you, Robert, ran over to that tree, up the road over there, and violently shook a branch. And then you ran back and continued your discussion with Rebecca, as if nothing had happened. Rebecca, you didn’t even seem to notice his bizarre behaviour.”

“Oh, I ignore it. He does that kind of thing all the time.” Rebecca explains, dismissively. “He claims that everything we do, even the smallest thing, changes the future. He says that he, and everyone who cares to be, is a ‘Time Lord’. Because the future is entirely contingent on what we do, here and now. So that’s the sort of thing he does to make one of his, supposed, changes.”

“But she disagrees with me,” says Robert petulantly. “I was arguing that if I do no more than shake a leaf, or an ant, out of a tree, the future is changed. So, I try to do things out of character, without any motive, as randomly as possible, to change the future of the entire Universe. What do you think?”

“Would you two like to come to our place for dinner on Saturday,” asks Bruce? “There is someone I would like you to meet.”

***

"What a lovely apartment and what a view! And this is little Ada, who only exists because of silly Robert shaking a tree?"

Over dinner, Robert asks Brian how he likes being a father. "It's a wonderful thing to bring a new life into the world." Brian says proudly.

This, apparently uncontroversial platitude, unexpectedly seems to hit a raw spot with Robert. "No! Ada's not a new life!" he says emphatically.

"What do you mean!" says Brian, feeling annoyed. But accepting that the older man is his guest; and a bit eccentric to boot.

"She's one of your living cells combined with one of Fiona's." explains Robert. "There was nothing un-alive involved."

Brian is still feeling a bit incensed. "True. But we've created a completely new and unique human being." he protests.

"Yes. That's obviously true. Just as a grower might produce a new variety of rose."

Is he trying to insult me? wonders Brian.

Robert continues pedantically: "But you did not bring her to life; any more than the rose grower created new life. She was initially just one of the millions of cells that are constantly dying and being replaced, in the colony that constitutes Fiona's, rather attractive, body. The only difference is that this one's specialised, not as muscle or skin, but as a meiotic cell, that needed to pool its chromosomes with a cell from your body, before replicating to become Ada."

Brian is pacified. Robert's a bit eccentric but he was not deliberately trying to be insulting. He was simply making a rather obvious factual point.

"As far as we can presently tell," Robert asserts: "there is only one life on Earth. We are all: animals; plants; fungi and bacteria; simply handing on that single life that, our ancestors in turn, inherited from the original living cell, that scientists call LUCA, the last universal common ancestor."

"So you claim there is never any new life!" says Brian incredulously, before he realises that they are using the word 'life' in a different way. He wants to assert that each new child is a new 'life', in the sense of living independently, as a new organism or colony of cells, while Robert wants to assert that all 'life', as in the attribute of being alive, is a continuum.

"As far as we can tell, there has been no new life on Earth since LUCA - 3.5 to 3.8 billion years ago", continues Robert. "Unless of course, Craig Venter, or someone else, is successful; and makes new life from constituent molecules, in the laboratory."

"So according to you," says Brian, laughing: "when we eat this potato, we are eating our own extended organism, part of the single life on Earth."

"What's strange about that?", asks Robert, taking another bite.

Then, when he can speak politely after swallowing: "Unlike many plants, that can consume inorganic chemicals, almost everything we eat, except water and some salts, is organic; and was once another part of the Earth's biota. A relative if you like." He loads his fork again waving it towards Bruce.

"Cells throughout the biota, of all living things on Earth: are created by cell division; clump together and specialise to cooperate, often as part of an individual plant or animal, that will outlive them."

"How can the animal or plant live longer than the cells that create it?" asks Brian, between mouthfuls.

"It's like Lloyds of London, that's well over three-hundred years old. The organisation of cells, that is us, can last very much longer than its individual members," replies Robert, sipping the excellent wine, that Bruce bought for the occasion.

"Few human cells live longer than ten years and about 60 billion cells die; and are replaced by others dividing, in our bodies, every day. In our lifetimes, even the longest serving of our individual member cells, will be replaced seven or eight times."

They both began to finish their meal, thinking their own thoughts.

When at last their plates where empty, Bruce asked: "You said something, back then, about plants living off chemicals - then what is Organic produce?"

"Organic has become a marketing word. It refers to the style of production, minimising insecticides and so on. It has little to do with the scientific definition - chemicals based on carbon."

"On the whole, plants consume chemicals, often cells broken-down to their molecular or constituents - many of them in-organic. On the whole, we animals eat plant or other animal cells - things that are or were recently alive - mostly organic. There is no such thing as an inorganic vegetable or meat. We should all eat sensible, good quality food, farmed sustainably. Forget the marketing techno-babble."

***

Very soon, after the men began this discussion, Rebecca, who has heard it all before, asked Fiona about her experience of motherhood.

She learns that Fiona's on maternity leave and misses work. Babies are amazingly demanding and much harder than she'd expected.

It's clear to Rebecca that Fiona, who's obviously very competent in the world of business, is having a hard time. She's new mother, now in her late thirties. She's not getting enough sleep and although Bruce is a great dad, and very supportive, she's close to cracking.

Rebecca offers motherly advice. Her own children have been through this and she's sensible and understanding. She and Robert are retired, she explains. They live on Bruce’s way to work and if Fiona would like a break or they need a babysitter later on, she and Robert will be delighted to help.

***

And so it came to pass, that Ada spent quite a bit of her childhood at Rebecca and Robert’s, particularly during the school holidays, often playing with their own grandchildren, who became her great friends.

Robert was always there for all of them, to suggest making something, read or tell a story or to argue with, about almost anything.

Not long after she first went to school, Ada's parents split up. Fiona’s career was blossoming and she said that Bruce was too stuck in his ways, like all engineers, unable or unwilling to evolve. But they remained in close agreement about her upbringing and now Ada had two bedrooms and a half-and-half week.

Robert and Rebecca became Ada’s rock. They comforted her and helped her to see that what was best for both her parents, was also best for her. And she shouldn’t be too hard on those new, often in her opinion, hopeless, people who came into their lives and sometimes into their beds.

They helped her understand that relationships are hard enough, without a petulant child disturbing things.

After a couple of false starts, Bruce found Angelina and soon Ada had a half-brother, Lyle. Ada assisted Angelina during the birth and has been like a second mother to Lyle.

Bruce admits that he wouldn't have met Angelina if it wasn't for one of Robert's silly pranks.

They were in the local pub and Bruce was bemoaning his latest bust-up and his inability to find the right woman, when Robert, suddenly, threw his coaster like a Frisbee. It collided with a couple of women across the room. Robert immediately went into his random event - Time Lord - routine: apologising profusely and offering to buy them drinks, while en-passant, introducing his friend, Bruce, to Angelina.

Bruce has always wondered if this 'random prank', that just happened to hit the friend of the women who has become his second wife, was more deliberate than Robert admitted. In any event, Lyle too, owes his existence to Robert.

Rebecca and Robert’s predictions turned out to be true. Fiona is successful; Bruce and Angelina are happy; and Ada and Lyle share additional stepsiblings; as well as step-cousins: Robert and Rebecca's real family.

So maybe Robert can manipulate the future?

***

When he was around seven or eight, Angelina became concerned that, as a late child in a mostly adult environment, Lyle seemed to have difficulty interacting with boys his own age. So, she joined him up in the local Cub Pack (junior Boy Scouts). Lyle quickly formed friendships with Wesley and Ibrahim, two other intelligent, rather nerdy, bookish boys.

Soon after he joined, the Pack went for a day in the bush. They lit a fire, with only one match, boiled water, for tea, and cooked jacket potatoes and damper in the coals and sausages on sticks.

Lyle loved it and was full of stories about the adventure. Ada listened with delight at her brother's excitement.

By the creek, where they had stopped for lunch, they found a slaty shale outcrop and Lyle wondered if there might be fossils interleaved between layers. So, he cracked a small slab of the rock open and sure enough, there was the impression left by a prehistoric leaf, preserved like a flower between the pages of an immensely old book. His friends started cracking open other pieces of shale and soon more impressions of fernlike leaves were found.

Lyle has loved dinosaurs from the time he could talk: "What does a dinosaur say, Lyle?" "Roarrr."

He could soon name dozens; and liked nothing better than being taken to the Natural History Museum to see the skeletons.

But Lyle had never found anything as exciting as his first fossil. Now, before his eyes, were several ancient fossils, that had been hidden for tens of millions of years, that he had actually found himself.

This was no longer the imaginary world of Kipling's Jungle Book, that the Cubs inhabited at their weekly meetings. These were just like those fossils in The Museum. These were his, that he had discovered, all by himself. Maybe he was a Time Lord, like Grandad Robert?

He excitedly announced to his friends that the shale deposit must be even older than the dinosaurs, because the plant leaves were similar to images on The Museum website, from the Palaeozoic Era, over 300 million years old.

They had just cracked open the tombs of once living cells, that had been buried there, all that time.

"But guess what Ada!" he said in amazement.

"I can't begin to guess Lyle," she'd replied, enjoying his excitement.

"Wesley said that I was talking nonsense and Ibrahim agreed. He said that I was talking Evolution, as if there was something wrong with that."

"Both of them said that fossils in rocks didn't prove anything. Wesley said that everyone knows that the world is six thousand years old; and God made it complete with all the rocks; and Ibrahim said he was right and I was wrong."

"But the fossils were right there in front of them! They opened some of them themselves. They are obviously formed horizontally, in flat layers of mud on the bottom of a lake. But the shale outcrop once had many metres of sandstone on top of it and we only see it now because it's faulted and tilted. So, it must have moved and twisted, over a very long time."

"Ada, I'm right, aren't I? How can they possibly believe that all this happened in the just four thousand years?"

"Well, I can understand that Ibrahim might find that fossils that he found himself confronting," Ada had replied. "Because his family is probably Sunni Muslim and they believe in the Old Testament creation story, the same as fundamentalist Jews and Christians. So, tell me more about Wesley."

"He lives near our school," Lyle told her. His parents work at a place called the Church of the Nazarene - they're American."

"Ah, that's a fundamentalist, protestant, Christian sect."

"You need to understand that as you get older, you'll meet people that believe a lot of things that to you will seem strange. And you have to remember, that what you believe may seem strange to them. It all goes back to what our family and carers believe - because that's part of our reality, the one we each grow up with as infants and children."

"What do you mean?"

"Well, you've believed in dinosaurs since you were tiny, because, in our family, we all believe that dinosaurs evolved from simpler animals, long after the planet formed but long before humans existed."

"They became extinct sixty-five million years ago and modern humans evolved around a hundred thousand years ago," added Lyle, displaying his geological knowledge. He's not called Lyle for nothing.

"Most people in our family believe that everything is in some degree of doubt," said Ada: " That's why we often argue about the truth of things. We like to learn about physical evidence that we could actually test ourselves, like fossils and DNA evidence of evolution. Other scientific theories, that have been tested, like Newton's Laws are accepted as working approximations, even when we know that they take no account of relativity. For us nothing is absolutely certain."

"But some children are brought up with certain knowledge, faith and belief, usually based on stories in an ancient book or handed down in their family. Think of the Cubs and your Jungle Book."

"For example, some families believe in gods that intervene in their lives; or fairies; or devils; or witchcraft; or the evil-eye; or curses; or that luck can be changed by things they possess or do; or that dead animals can go on living without their bodies."

"These are purely imaginative things that are unprovable, yet undeniable. Because they are undeniable, they believe them to be true. But because they are unprovable, their actual existence depends entirely on faith. Like the stories of: Mowgli, Akela, Bagheera, Baloo and Shere Khan in the Jungle Book", they're in the heads of the believers."

"We know when the Jungle Book was written and by whom."

"Rug-yard Kipling," put in Lyle, getting it slightly wrong.

"But suppose Rudyard Kipling wrote them two thousand years ago; and some people thought the stories truly happened? They couldn't be disproved and the believers would take them on faith."

"That's funny," Lyle laughed. "At Cubs we do shout: 'Akela, we'll do our best.' but we know that The Jungle Book is just a story and she's not really a Wolf."

"But children brought up in families, where imaginative characters in their book are thought to truly exist, must have faith. With faith, they have no difficulty in believing unprovable things, that appear in their book, or perhaps in other family stories. For example, they might believe in angels; or the power of prayer; or in the importance of particular rituals; or in life after death. They have faith that God made the world, complete with folded sedimentary layers and fossils, to look like it's thousands of millions of years old."

"Maybe he did?" Lyle had asked.

"Exactly. That's another faith-based belief we can't disprove - like the one that he created everything and everyone a month ago, complete with all our memories of the past."

"Or a second ago!" Lyle added.

Ada had been delighted with his quick understanding but was concerned that she had injured his new friendships.

"Strange ideas are so common that we all need to learn to get on with each other, no matter what stories the other may believe in."

"I like my friends, even if they do believe some funny stories. There's nothing wrong in that is there?" asked Lyle.

"No. Not if they still like you, once they discover that you have different beliefs."

"But it's good to spread a bit of doubt in people's minds. Argument is good, and wrong beliefs should be avoided where possible. They can be harmful."

"How?" he'd asked.

"Well, if someone comes to the door and tells, you or I, that an angel brought the Book of Mormon to Joseph Smith; or that the Angel Gabriel dictated the Koran to Mohammad, they first have to persuade us that angels are real. To you and I, angels are like Hobbits or the Wizard of Oz, they belong with Mowgli in the unreal-world of imagination. So, this makes less sense than telling us that: a message was delivered by unicorn. After all, someone might genetically-engineer a unicorn."

"Grandad Robert asks them in," said Lyle. "He's funny!"

"Well, Grandad Robert likes to spread uncertainty among the faithful. He also believes that he can randomly change the future. So, he likes to do unusual or unsettling things."

"Once, he suddenly ran into the garden and blew a child's unrolling whistle in the middle of a serious discussion about faith and evidence. The visitors quickly ran away after that. Later that day, a Mormon was injured crossing the road. Grandad claimed that he was responsible, as the car and the Mormon would not have been in the same place at the same time, except for his random whistle event."

They both laughed.

"Being persuaded to change their religion or to join a cult, by a door-to-door evangelist, could be upsetting to a faith believer's family, or others who love them, but it's not much for us to worry about. It's important for a kind society that people should be allowed to believe in any nonsense or do dangerous things, provided it harms no one but them. But it's not always a laughing matter. A faith believer might be persuaded that they will get a special treat in heaven, if they do something terrible to nonbelievers - like knee-capping a neighbour or becoming a suicide bomber."

"Over the centuries millions upon millions of people have died in faith-based conflicts. When the opposite sides, are each convinced, by their faith, that they are doing their god's work. Faith can be a dangerous thing, not just for the faithful, but for others."

***

As Ada got older, she laughed at Robert's idea that he could change the future. But not because the future doesn’t change, with everything we each do. It obviously does. No one could think otherwise. That’s just cause and effect, the very means by which we observe the direction or arrow of time - from past to future.

No, she argued that Robert was not making random decisions. What he thought were unpremeditated actions, like suddenly shaking a tree or throwing a coaster, are, in fact, part of what he is, what he does, a part of his personality. Just like a bird in flight suddenly, and apparently randomly, changes direction; or a wheel falls off a toy car.

She argued that Robert is bound to do these things, as a result of who he is and what he believes. Like the broken wheel, it’s just physics and chemistry.

Robert persists in believing that he has ‘free will’ and is able to take random actions, in contravention of his expected behaviour, the normal reaction to his environment, that has been programmed into him, by his life to date. He still does random bizarre things, that he claims prove that he is indeed a free agent - a Time Lord.

They regularly argue about this. Robert suggests that Ada’s position is equivalent to saying that everything in time is already predetermined, that 'free will' is an illusion. Ada says that if Robert is right, the future is constantly in a state of flux. It is being changed second-by-second. Yet, not just by humans. It must be changed by every living thing, for example, a bee that stings and causes an accident; or a bacteria or virus that mutates and results in an epidemic.

***

Since she became an attractive young woman, Ada has had several serious boyfriends. With each new partner Robert has reasserted his claim to be a Time Lord – adding in parenthesis - that so are they, if they care to be, as can be every living thing.

Indeed, he's revised his old definition, involving negative entropy, and recently been claiming that this is a good definition of life: something with the potential volition to change the future.

Ada just as firmly insists that, this is patent nonsense. Einstein showed that time is just another dimension like height, breadth and depth, and like them, it is already defined. We are just moving through time like the characters in a 1930’s movie. They are forever condemned to do exactly the same things, no matter how many times we watch them.

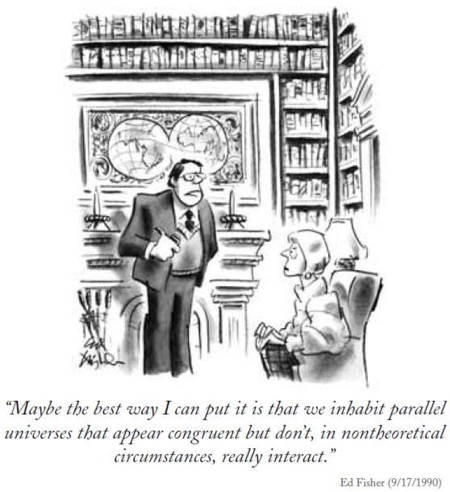

The boyfriends inevitably propose the parallel multi-universe theory, widely promoted by popular science fiction. But both Robert and Ada have long ago dismissed this as irrelevant, as adding nothing to the debate, except as a thought-experiment, a version of the anthropic principle, a philosophical explanation for us being here at all.

They agree that the Universe, by definition, comprises all that we perceive or can rationally deduce from those perceptions. So hypothetical, unperceived universes, beyond our verifiable deductions, are of no interest, the scientific equivalent of religious imaginings, involving mythical heavens and so on.

from The Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker

***

Thirty years have passed since Robert shook the tree. Ada is receiving her long-awaited PhD in Chemistry.

For her thesis, she examined the chemistry of RNA, and the proteins thus expressed, in the brains and spinnerets of huntsmen spiders. There had been a ready supply of these large, relatively harmless and beautiful spiders in her student share house.

She was able to grow the protein molecules, encoded in the spider DNA, into a super molecule, that is the strongest known organic fibre, and can be readily manufactured using her modified transcriptase, synthetic RNA, replication method.

But she was side-tracked when she found that the spider neuron structure could be made to replicate indefinitely and, when bathed in suitable organic nutrients and enzymes, could grow into an organ of almost any size. She then used recombinant DNA technology, to add a light emitting node to the neural cells, that facilitates an input-output interface to electronics.

Hers were the size of a grain of rice but a number of commercial companies are already exploiting the ‘Ada’ process.

One has grown a grapefruit-sized organic brain on an electronic substrate, like a small interactive screen, that communicates with its inputs and outputs. This ‘Ada’ spider-brain is already learning rapidly; and demonstrating human-like artificial-intelligence.

Now in their 80’s, Robert and Rebecca have been de-facto grandparents to Ada, for as long as she can remember. They're sitting proudly in the audience at the graduation and presentation.

To everyone's consternation, it's just been announced that Ada is also to be awarded a Nobel Prize for her artificial brain discovery.

She's been invited to speak.

She's witty; informative about her findings and the processes that led to her discoveries; and modest; ending with: “…and humanity owes my discoveries to my existence. And I owe that, to my adopted Grandfather, Robert - who claims to be a Time Lord.”

November 2013 - December 2015