What is electricity - really?

Above I invited you to think of electricity as a fluid of electricity running through a conductor that acts like a pipe.

According to our present conceptual model electricity is due to the movement of electrons in a conductor. Electrons are negatively charged fermions (particles that make up an atom) that are generally happy to hang around an atom to balance the positive charge of its nucleus. Read More...

Electrons are envisaged as milling around in the general vicinity but often at a great distance, relative to the size of the nucleus, like planets around the sun. The outer electrons define the physical size of an atom. Contrary to some pictures you might have seen they do not orbit elliptically like planets but occupy a space determined by their wave function and energy state. They are happy bouncing around in this space unless something, like a photon of light or heat, encourages them to jump to another energy level.

Conductors and insulators

Some elements, like the metals, bond to each other in such a way that outer electrons can pass energy on to the next; or perhaps get shared in one big cloud.

By stimulating electrons to move we can make them carry energy along a conductor but this is more like the baton in a relay or an ‘Indian wave’ in a stadium than a flow of water. Each one in the chain just gives the next one in line a ‘shove’; pass it on. The ‘shove’ goes down the conductor and after passing-on the ‘shove’ each electron continues to hang about as before.

On the other hand, non-metals tend to form molecules in which the electrons are not free to pass energy on. A material in which no current can flow we call an insulator. Read More...

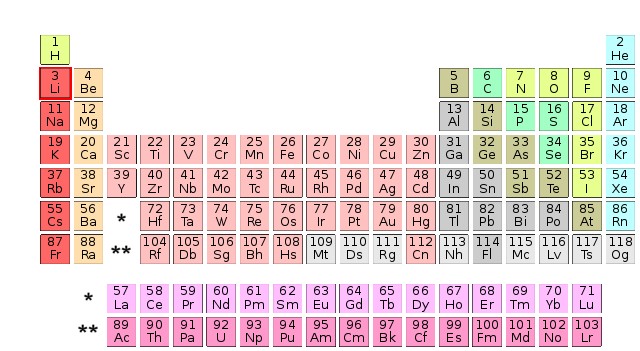

Whether an atom is a metal or not depends on the number of protons in the nucleus. After disregarding the first two (hydrogen and helium), elements can be lined up nicely by their proton count (roughly half their atomic weight) in a table: the first-row pair of 8 then 18 then 32 columns wide; so that every 8th, 18th then 32nd is similar in properties; for example: a noble gas, a halogen or an alkali.

This pattern was observed by chemists before it was explained. Once recognised it allowed chemists to see the gaps and find the missing elements. This regular pattern of repetition is called the periodic table of the elements.

Quantum mechanics now provides a model predicting/describing/explaining this observed behaviour.

Metals (the salmon-coloured elements above) are not the only conductors. Some non-metals like carbon have one form, graphite, which is a good conductor and another, diamond, which is a good insulator.

Selenium, another non-metal, has semiconducting properties and was widely used before silicone in solid state rectifiers. As a schoolboy I built several battery chargers and power supplies employing selenium rectifiers which were then easily obtained from disposals stores.

Black phosphorous is another non-metallic conductor.

If an electron is stripped from and atom (or it acquires extra electron) it is said to be ionised and if the whole atom is mobile; for example: in a fluid (gas or liquid) the whole atom can act as a transport for electrons or of positive charge (an excess of protons).

For example, salt water is a good conductor and even the earth (rocks and soil) can be used as the return conductor in a circuit.

As kids we used this in our one-wire telephone to friends in neighbouring houses.