The recent Australia Day verses Invasion Day dispute made me recall yet again the late, sometimes lamented, British Empire.

Because, after all, the Empire was the genesis of Australia Day.

For a brief history of that institution I can recommend Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World by Scottish historian Niall Campbell Ferguson.

My choice of this book was serendipitous, unless I was subconsciously aware that Australia Day was approaching. I was cutting through our local bookshop on my way to catch a bus and wanted something to read. I noticed this thick tomb, a new addition to the $10 Penguin Books (actually $13).

On the bus I began to read and very soon I was hooked when I discovered references to places I'd been and written of myself. Several of these 'potted histories' can be found in my various travel writings on this website (follow the links): India and the Raj; Malaya; Burma (Myanmar); Hong Kong; China; Taiwan; Egypt and the Middle East; Israel; and Europe (a number).

Over the next ten days I made time to read the remainder of the book, finishing it on the morning of Australia Day, January the 26th, with a sense that Ferguson's Empire had been more about the sub-continent than the Empire I remembered.

Like many Penguin low cost titles Empire is already quite long in the tooth. It was written not long after 9/11 and was published in 2003, along with a Channel 4 television documentary. Niall Ferguson lives and teaches history in the United States where he has argued that the US is failing in its role as the natural successor to the British Empire. He is an historian to the right of centre, critical of the British Welfare State and 'big government' generally.

There are hints of these views throughout Empire but they were no doubt tempered by a vast list of people who contributed to the overall production. Their names cover over a page and a half of finely printed text at the end. The book suggests that the British Empire's fatal mistake was to enter the First World War against Germany. That the largest Empire the World has ever seen could thus have survived; and by implication, that this would have been a good thing immediately led to accusations that Ferguson was an apologist for all the evils perpetrated by the Empire. Yet, as he has pointed out, the book focuses more on those evils than the Empire's positive legacies. Notwithstanding this controversy, for its popular style and wealth of historical detail, Empire is a 'page turner'.

Thinking back, my first formal awareness of the British Empire was in Primary School and that was during its final years: after Partition and after Palestine. In those days being part of the British Empire was still a matter of general pride in Australia, reinforced at school assemblies and in the media. Australians still carried British passports, flew the Union Jack above the Australian Ensign and stood to attention to sing God save the Queen, even at the cinema. In my family, recently emigrated from England, its legacy, talked of with pride, was alleged British technological leadership. I had no trouble listing: steam; steel; electricity; vaccination; anaesthesia; antibiotics; radio; television; jet engines and many more as British inventions. The most important legacies of the Empire: the Westminster System of representative government and the Common Law were taken as givens.

Thus, since I was a child, January the 26th has been the day Australia has celebrated the day in 1788 when the Union Jack was raised in Sydney Cove, heralding the foundation of the very first European colony on this continent and claiming this first foothold for the British Empire.

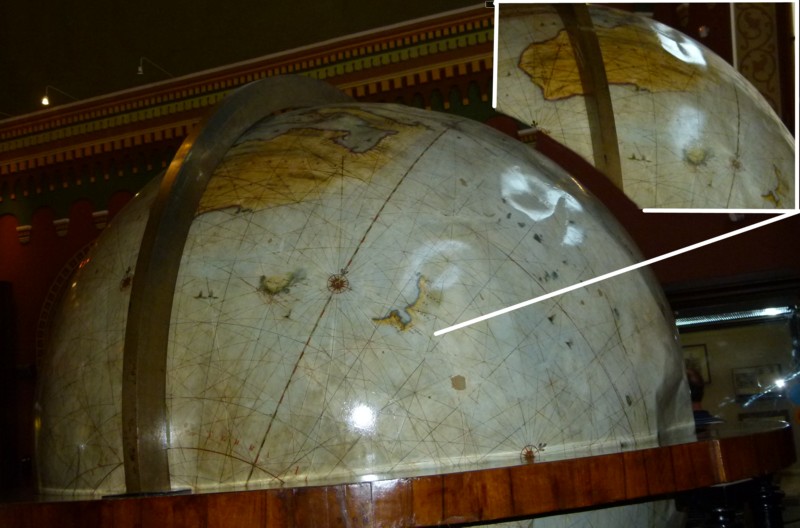

Australia, Terra Australis Incognita, on the maps, was not completely unknown in Europe. During a visit to Moscow in 2013 I discovered a huge globe of the Earth in the State Historical Museum. Created in 1650 it clearly shows, with some accuracy, the: northern; western; and part of the southern; coasts of Australia. Even the west coast of New Zealand is partly marked. The principal missing bit is the east coast of the continent. As all Australians know, this was not delineated until Cook's scientific voyage in 1770.

The only other area in which this globe differed substantially from the little modern one, sitting across from me now, was the missing coastline around Alaska and the west coast of North America, also to be delineated by Cook.

Most of the partially mapped Terra Australis Incognita was quite clearly within the hemisphere that had been granted to the Portuguese for colonial exploitation by Pope Alexander VI and his successor Pope Julius II. The Protestant English and Dutch failed to recognise papal authority in this matter and subsequently took the nearby (East) Indies from Portugal and in their own carve-up gave most of it to Holland. Yet neither Portugal nor the Dutch were tempted to colonise the apparently inhospitable and commercially worthless continent to the south.

All that was about to change. After the Seven Years War (1756 to 1763) Britain found herself with a growing empire, including new territories in North America. These North American colonies would soon to be reduced when, in 1775, thirteen of the colonies south of the St Laurance River rebelled against London's rule. As Niall Ferguson points out, at the time these colonies were no great loss as they were not particularly profitable. It was an interesting example of political short-sightedness. But now a new place to send and hopefully reform Britain's growing crop of convicts was needed. The empty southern continent beckoned.

Years of debate and planning followed, plagued by delays, but on the 13th May 1787, an initial fleet of eleven ships, carrying around 1,487 people as well as stores, and livestock, set sail from Portsmouth to found a new penal colony at Botany Bay in the antipodes. Only the South Island of New Zealand was further away.

Nevertheless this 'First Fleet' was a triumph of British naval seamanship, travelling 24,000 km (15,000 miles) without losing a ship and at a cost of only forty-eight deaths, about double cruise ship deaths over a similar timeframe today. In partial offset, 20 children were born during the trip.

The fleet arrived in Botany Bay between 18th and 20th of January 1788 where they discovered that the aging Sir Joseph Banks, by now President of the Royal Society, had oversold his youthful memory of Botany Bay as the perfect location for a colony. Fortunately, a much better site was quickly discovered just a few miles up the coast at Sydney Cove within what turned out to be one of the most commodious harbours in the Empire.

Like all such settlements there were initial struggles to survive, not helped by near failure of a contracted-out Second Fleet. Nevertheless, despite these trials and tribulations, within a few decades the colony had spawned several satellite settlements in Tasmania, Western Australia and Queensland and was attracting free settlers from the 'old dart' seeking their fortunes. Thus by 1840, when the transportation of convicts ceased, Sydney was thriving and reputedly had one of the highest standards of living in the world. In 1825 a Legislative Council had been the first step to representative self-government with the first elections held in on the British model in in 1843. The discovery of gold in 1851 began Australia's reputation as 'The Lucky Country'. Since then fortune has generally smiled on Australia, not just for the glitter of gold and gems; but for wool and wheat; coal and iron ore; uranium and rare earths. Migrants flooded in and continue to do so. Soon the secondary and tertiary sectors outstripped primary production and Australia had become the most urbanised country in the world. From its birth as a penal colony, Australia now ranks second in the world on the Human Development Index after Norway (where the climate leaves something to be desired) and an Australian born today can expect to live over one and a half years longer than a baby in the 'mother country' and a full two and a half years longer than a baby born in the USA.

But today a section of aboriginal Australia sees no good in this. Indigenous people on average have a life expectancy over a decade lower than other Australians. Given that this only applies to the proportion of the indigenous population who live disadvantaged lives on the fringes, the actual situation for these people is much worse. These marginalised people are more likely to become welfare dependent; to be physically and sexually abused; and to be jailed that other Australians. It's a matter of extreme shame that we as a nation have not found a solution for these people and the situation has actually been made worse by past attempts to improve things.

Thus many call this 'Invasion Day' and there have again been mass demonstrations and for the media's cameras, a little violence.

'Invasion Day' because, of course, this was not actually an empty continent. True, it was very sparsely inhabited, with considerably less than half a million people across an area substantially larger than the whole of Europe, including the British isles. It's little wonder that to European eyes this land was largely deserted and underutilised.

Yet it was not uninhabited. Modern humans had been here for at least 40,000 years. This has been confirmed by various means of tool and artefact dating and more reliably by DNA information. Today very few people do not have a recent European ancestor. But both mtDNA and Y-DNA haplogroup markers from isolated communities suggest that in 1788 the Australian Aborigines, particularly the south where external contact was close to non-existent, had not then shared a common ancestor with the invading Europeans for about two thousand generations or 60,000 years. See When did people arrive in Australia? on this website.

Among an estimated 350,000 inhabitants at the time of British settlement there were an estimated 250 tribal groupings, each with their own language, within each of these were a number of clans often with language differences. Relationships between these disparate language groups followed the usual human lines. They were marked by inter-tribal tensions, the occasional fight and elaborate rules about entering another's country. Thus spears, shields and throwing sticks were standard accoutrements for adult aboriginal males and fighting was part of both the progress to manhood and ritual retribution for misdeeds.

So, despite some later resistance to losing territory, this was not a single unified culture capable of repelling a group of Europeans that had just concluded the Seven Years War and was well armed, half expecting the French to turn up. And turn-up the French did within days, though neither European group knew if they were at war or not. So the leaders opted for 'not' and the French under Jean François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse, who had recently suffered severely from a native attack in Samoa, were allowed to recuperate and repair for six weeks by fellow Europeans and were then helped on their way.

While the Cadigal people in Sydney and Gweagal at La Perouse may have been put out by groups of strangers setting up camp on their country, to others in their Eora language group (encompassing the greater Sydney area) this was not a cause for joining as a nation in an attempt to reject the usurpers. Thus there was no organised Maori-style resistance, as was later experienced in New Zealand, or coordinated attacks, as suffered by the French at the hands of Polynesians in Samoa. This very lack of effective resistance confirmed apparent indigenous indifference to losing territory.

Of course this 'invasion' was going to happen sooner or later. Even if Philip and his fleet had not turned up it's completely unrealistic to imagine that Australia could have been left alone and essentially uninhabited into the 21st century.

And if an indigenous people had to choose which colonial power to be invaded by the British were a pretty good option. Other invaders at the time might have been the French or Portuguese or Dutch. Later, and even worse, it might have been the Japanese. Given the record of those colonial powers in respect of indigenous peoples elsewhere, aboriginal Australians got by far the best deal. The Japanese held competitions for the most killed, with extra points for brutality, but the Iberian powers were not much better. For example Pope Nicholas V in a Bull, Romanus Pontifex, had commanded Portugal's King Alfonso V to treat pagans discovered in these new lands as follows:

[confiscate] all movable and immovable goods whatsoever held and possessed by them and reduce their persons to perpetual slavery.

This was an injunction that both the Spanish and the Portuguese did their best to live up to.

On the other hand to the general consternation of white settlers, the British administration was soon jailing and hanging white men in New South Wales for the mistreatment or murder of indigenous people and by 1833 the Empire had abolished slavery throughout its colonies, enforcing equal rights under the law.

So today's protests against celebrating the achievements of the Nation on the anniversary of the European colonisation seem a little odd, if by now entirely predictable.

Aboriginality in Australia is defined by one's personal identification. As with gender, one just needs to feel aboriginal. Nevertheless, those who identify as aboriginal typically have at least one indigenous ancestor. Yet today almost every indigenous person also has at least one European ancestor. So what if those European ancestors had not arrived? As I have repeatedly asserted, everyone alive today is only here because the past took place exactly as it did. It's pointless to rail against the past because if it had not happened, just as it did, none of us would be here to be aware of the change.

Those who identify as aboriginal are a tiny minority in Australia. At the last available census (2006) Aborigines and Islanders totalled just 517,200 representing 2.5% of the Australian population and those living in poverty on the fringes are a proportion of these. Not all aboriginal Australians live in poverty. Many are similar in education and health to other Australians. I have worked with several professionals who have lifestyles virtually indistinguishable from the mainstream.

If it was only this tiny minority who want this change of date it would be anything but a democratic demand.

But all protest is actually about the perceived future. What message is being sent by celebrating this day? Thus the protests have engaged a great number of non-aboriginal Australians who seem to be principally distressed by the accusation of theft and apparent insult celebrating it represents to those identifying as aborigines.

And this is where I get back to Empire. At one time similar debate existed over the celebration of Empire Day. The alternative, Commonwealth Day was promoted by the Roman Catholic church that was reacting to protestant imperialism.

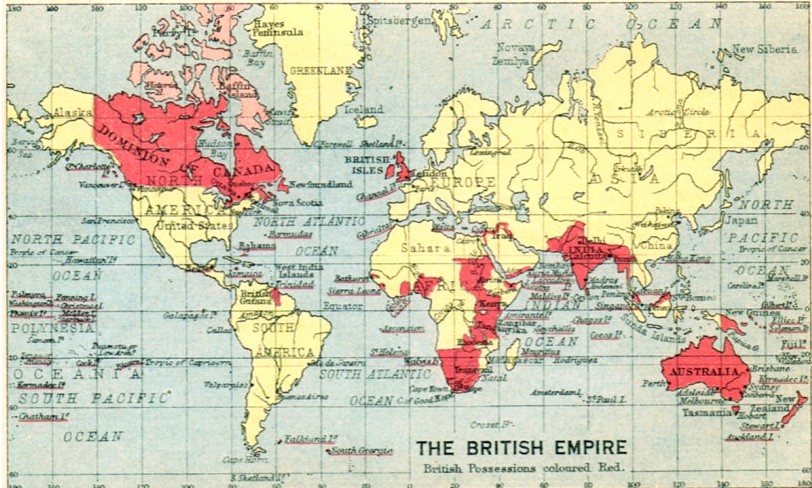

I'm old enough to remember Empire Day; when imperial honours were handed out; when fireworks celebrated the late lamented Queen Victoria's birthday; when the world map in our classroom seemed mostly red:

It was a time when older Australians still proudly boasted of having fought for the 'mother country' in two world wars. See Bonfire (Cracker) Night on this website.

Like Empire Day these practices and sentiments no longer exist. So when Britain briefly reasserted her imperial might in the Falklands, the Australian public watched on with interest. But no one with any credibility called for us to join in, as Australia had instinctively done until the 1950's. Yet Australians still quite like the British Queen. She is, after all, Queen of Australia too - even if that's because Australians can't achieve consensus over a constitutional alternative.

The Empire still persists in other ways too. Although we've cut almost all material ties and long since disposed of appeals to the Privy Council, Sterling, Imperial honours; Imperial weights and measures; British trade preferences; and British passports; we still retain all those beloved British place names. Queen Victoria still stands on numerous plinths, along with 'Albert the Good' in some places, like across Macquarie St in Sydney, and both our navy and air force are still 'Royal', like many other of our institutions, from hospitals to animal homes. The Empire is as much a part of Australia's remembrance of the past as it is of Britain's. And I suspect it's more fondly remembered here and in Canada and New Zealand than even at home, where as Niall Ferguson argues, it became a dead weight in its final days.

So what about this date?

January 1st 1901 was the actual date that Australia as a nation came into being. But that's no good, it's already a holiday. So is Anzac day - remembered as the day Australia lost her innocence and faith in British commanders as a result of our greatest wartime defeat. Celebrating the fall of Singapore as Australia Day would be gilding that lily.

Maybe Edmund Barton, our first PM's birthday is a candidate, like George Washington's in the US? But our first Prime Minister didn't need to fire a shot to say farewell to British rule. And that's just as well because he was renowned for being 'tired and emotional' by the end of the day, earning the nickname 'Toby Tosspot'. Handing him a loaded gun after 6 o'clock would probably have been ill advised. What about other birthdays? Perhaps that of our first governor, Phillip, or the most illustrious one: Macquarie. Yet how would that be better than the present date? I'm at a loss.

Some have said that no date is acceptable for celebration of the Nation, 'for all is vanity' or hubris or nationalism. And who are these so called 'better' people being feted anyway?

I disagree. We need some appropriate date. I like an excuse for a holiday and see merit in having a special day to celebrate new citizenship. And when it comes to the awards and honours I support the Australian principle of recognising people for real lifetime achievements, in contrast to the many spurious awards handed out to media celebrities or in the old Empire on the basis of patronage or inherited title.

I notice there is a suggestion on social media that we should choose May 8. May8 - mate - get it? It seems ridiculously frivolous to me but then I'm old enough to remember the debate before we went decimal in 1966 when those who disliked the 'Dollar' for it's US associations proposed instead the: Austral; Roo; Emu; Kanga; Quid; Oz; Dinkum; or Digger:

"Ticket to the city? That'll cost ya five diggers and three emus May8!"

The Prime Minister's pick, fortunately forestalled by public outcry, was the Royal. To me May 8 seems to be about as frivolous as trying to make Waltzing Matilda (a song about a thief who suicides; that has supernatural overtones; and two different competing tunes to boot) the National Anthem. But then I'm way past gen-Y or millennial and - you know who you are - are the future leaders. In time you will no doubt do as you collectively want.

So I'm an 'old fuddy-duddy' and in the absence of a better one I'm all for keeping the present date. I'm not at all sorry that the British set up a colony here in January 1788. Had they not I would not be alive. Nor would my children.

In summary, Australia has a lot to celebrate and it all began with the birth of modern Australia, like Canada and New Zealand and dare it be mentioned, the USA, in the capable hands of the same midwife, the once great, but these days gone and seldom lamented, British Empire.

Footnote:

Alas, Australia Day is over for another year. Pleasant drinks with friends on 'The Rowers' balcony overlooking the harbour turned out to be the pinnacle of our excitement, although I did get a small fright when a jet fighter roared close overhead earlier. Now all we can look forward to is insipid Commonwealth Day in March (a different one to that preferred by Cardinal Mannix back then) accompanied no doubt by some more public fireworks; but only if ignited by licensed experts.