The following family history relates to my daughter Emily and her mother Brenda. It was compiled by my niece Sara Stace, Emily’s first cousin, from family records that were principally collected by Corinne Stace, their Grandmother, but with many contributions from family members. I have posted it here to ensure that all this work is not lost in some bottom draw. This has been vindicated by a large number of interested readers worldwide.

The copyright for this article, including images, resides with Sara Stace.

Thus in respect of this article only, the copyright statement on this website should be read substituting the words 'Sarah Stace' for the words 'website owner'.

Sara made the original document as a PDF and due to the conversion process some formatting differs from the original. Further, some of the originally posted content has been withdrawn, modified or corrected following requests and comments by family members.

Richard

Stace and Hall family histories

a summary

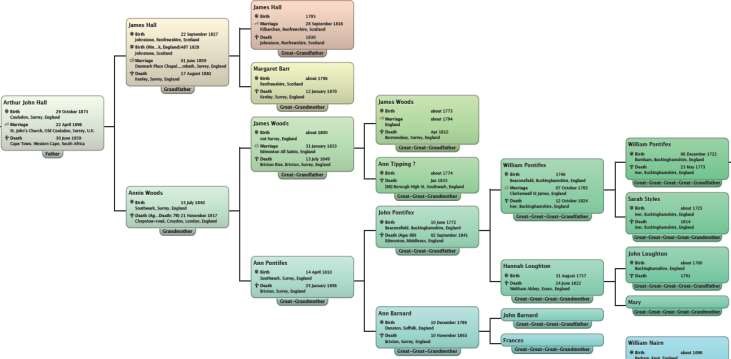

Stace Lucas Bannister Fawkner Peed Hall Venables Mears Cutbush Nairn Pontifex

Compiled by Sara Stace, 2013

Norman Edward Stace (1918 - 2008)

Corinne Helen Christine Hall (1915 - 2011)

Helen 1942

John 1943

Peter 1946

Brenda 1949

Nigel 1957

|

Norman, Corinne, Brenda, Nigel, John and Narelle visited New Zealand in 1969. They are in this photo with Thora, Gordon, his wife and Rodney Stace. |

|

Explosive Manufacture in Wartime 1940s

The following story was written by Norman Stace in 2003. It has been lodged with the Australian War Memorial:

Purely Personal Recollections of Norman E. Stace

Our son Peter has asked me several times to write a personal account of the WW2 experience, making high explosives in Australia. I think he had ideas of “bang-bang” and everything being exciting, noisy, and heart-stopping, but in fact the first step in making explosives is to plan, right from the very beginning, NOT to have bangs in the factory. Later in the overall picture, of course, the explosive should go off at the right milli-second. On the battle-field; not in the factory!

This early planning results in a detailed set of operating standards and procedures, which must be thoroughly adhered to at every stage of often very complex processes. Naturally, this doesn’t lead to much excitement; In fact, at times boredom can occur, calling for strict self-discipline -- for example at half past three on a frosty night shift. So in principle making explosives is not different from any other exacting industrial process.

Australia had commenced manufacturing munitions at a low level early in the 1900’s: in fact explosives were made, for mining and quarrying, in the 1800’s. However during WW1 many Australian chemists (I mean real chemists, not pharmacists!) were sent to Britain to work in the great new factories built there to feed the insatiable demand for war-time supplies – particularly for shells: cordite to propel them, and high explosives to fill them.

WW1 was the first so called “technological war” which showed that armies and fleets could function -- indeed exist – only when backed at depth by modern industries. So when the war was over, the returning chemists could envisage the need for Australia to arm itself, using the skill and experience they had gained in Britain.

Between the wars, Australian industries made great strides, and the Federal Government set up, mainly in Melbourne, a munitions complex making guns, ammunition, warships, aeroplanes and the necessary explosives. Thus when WW2 broke out in 1939, a great expansion was to take place, and it soon became obvious that a real shortage of chemists existed. Without some action, it would be impossible to operate the new chemical/explosives complexes planned to be built in Melbourne, Ballarat, Adelaide, Albury and Sydney.

Well, Peter, where does your dad fit in?

In 1939, just as the war began, I graduated in New Zealand with a Masters degree in chemistry, and was awarded a lucrative 2-year Fellowship in industrial chemistry at the University of Otago in Dunedin. The war certainly started badly, and with several other good friends I volunteered for a scheme to train as a junior officer in the Royal Navy in England. Much to my chagrin I missed out: the others were accepted. My professor didn’t comment, beyond saying “be patient”. Later I was balloted to be called up for the army; again, nothing happened.

Right at the end of 1940, Corinne and I were married. (Ah, youth! Best thing I ever did!)

Early in 1941, my Professor (who had been made Scientific Advisor to the Government) flew to Australia, and when he returned things started to become clear. I was asked if I would be interested in joining a scheme for trained chemists to go to Australia for the war effort; I certainly was: again I was advised to be patient.

After a couple of false starts, and a bout of pneumonia, I found myself in a group of chemists and engineers on board a small liner leaving Auckland for Sydney; blacked out and escorted by an RAN warship. On arrival on July7 1941, (how impressed we were by the Harbour & the Bridge!), we were met and entertained at dinner by the Australian Chemical Institute and put on the overnight train to Melbourne (first class sleeper, very impressed). We were met by a large group of senior executives; taken to an office and signed on to the Australian payroll; given an astonishing sum of money for “expenses to date”; given another sum as “advance of salary”; told how to claim for expenses, which seemed very liberal; given advice on accommodation until we settled in. All most agreeable. We were then entertained at a slap-up lunch, and told to look around Melbourne. In the next several days our group, which was the first of several, was shown over the Maribyrnong Munitions complex. We saw cascades of 303 ammunition (they could make several millions daily); gun forging, tempering, machining and assembly; large-scale forging of naval shells and aircraft bombs; fuses for artillery shells (looking like thousands of wrist watches); batch after batch of shells being filled with TNT; production lines filling hand grenades with a mixture of TNT and barium nitrate; a quick look-over the explosive plants; the R&D department; the library; the Metrology section where they could measure dies and screw threads in ten-thousandth’s of an inch. This is only part of what we saw: the effect on our group was one of overwhelming astonishment. We were certainly motivated to become part of Australia’s war effort.

Our guides were sometimes as wide-eyed as we were; apparently our tour of inspection was the first of its kind for thoroughness and scope.

Then the group was broken up, and we each went to our allocated sections; several to Research; some to Development; others to Factory Laboratories and three to explosives manufacture – I to TNT, one to Nitro-glycerine, another to Cordite. It was my good luck to find a fellow Kiwi at TNT: we had several mutual friends, and he went out of his way to show me the ropes.

For the next fifteen months I was on shift work, which was an ideal way of learning every detail of a plant which in several stages reacted concentrated sulphuric and nitric acids with toluene, ending up with the finished product looking like cornflakes. The chemistry was very simple but there were some surprising little deviations from theory, and these caused the crude product to contain impurities which had to be removed. The plant was based on processes devised in Britain in a hurry early in the First War, and the purification steps were cumbersome and unhygienic. The chemist in charge of our plant had the bright idea of changing several key variables – Temperature, pH, Time, Concentration; and a quick trial showed promise. So he disappeared into the main Development lab, and successfully came up with a greatly improved practical process. I wondered if our old rattly plant was to be upgraded, but was told only the new, much larger plants would benefit. This made sense; we could make a mere 25 tons weekly: by contrast ICI’s just-commissioned plant a few miles away made 80 tons and the two new Government factories under construction were each designed for 100 tons weekly. (These latter plants never reached their potential, but more about that later).

Imbued by this example, I looked for a comparable project, and made a thorough analysis of the various plant operations; soon it became clear that a great improvement could be made by a simple re-arrangement – a 60% increase in capacity with no extra labour, and at modest cost. My report attracted approving comment from the senior staff but no action resulted. (Again, more about that later).

A most important event happened on December 5, 1941---note the date. Dear Corinne arrived, having traveled across the Tasman by the American Matson liner, and we were joyously re-united.

Pearl Harbour changed everything, including TNT production in Australia. We soon had an example; one evening I arrived for the night shift, to find the afternoon chemist in a high state of excitement; he had just been phoned from Geelong docks where a shipload of American TNT was being unloaded. A sling had broken, some boxes had fractured and bare explosive was lying on the wharf: what to do? He advised the alarmed wharfie to gently sweep up the scattered flakes and to put them into buckets of water and then just carry on. Rumour spread that 10,000 tons was on the ship, and I cannot confirm this, but later on towards the end of the War, I was reliably informed that USA had sent a total of 30,000 tons to Australia. Such amounts overwhelmed our domestic output, but were tiny in comparison with the half million tons scheduled in US for 1944.

The first general effect of Pearl Harbour was increased pressure for output at all levels: the Japanese were at our gates, and no-one could foresee how things would turn out. This push for production had a unhappy outcome. One sunny afternoon I heard a thump and felt a shockwave: not far away a brown-grey cloud was rapidly ascending from the anti-blast walls of a nearby plant. My first action was to go quickly over our unit to check if all was OK. From the top storey I had a clear picture of what was going on; a Detonator magazine had gone up and flames were licking in the wreckage. Men in bright scarlet overalls (the Det operators all wore these) were running out hoses, and soon had the fires under control. For a short time, with these brilliant uniforms, the scene was like a stage production of Hades, but this was no make-believe. The official enquiry, which was published, was quite damning. Under pressure for output, protocols for the magazines had been breached, and boxes were stacked higher than they should. A tumble was presumed to have set things off.

I found this spell to be interesting, although shift work was at times physically trying. Afternoon shift was the best: it was called “gentleman’s hours”; get up late, enjoy a pleasant lunch, stroll to the city for window shopping, and catch the tram to work. But the first two night shifts were always testing, sleeping in daytime I found difficult: today we would call it jet-lag. So I borrowed books on explosives from the Research library, which had an astonishing number and if my head started to droop, or the office grew too cold, I knew it was time to go into the plant and chat with the men who all had the same problem. For a while, until austerity clamped down, we supervisors could walk to (a rather distant) staff canteen for a fine mid-shift three course meal, and it was always good to “talk shop”, with fellow chemists and discuss the problems of the day. Sometimes one would be invited to look over another plant in the factory; I don’t know if this was legal, but in the middle of the night who would know? In this way we all got an insight of what was an eye-opening variety of activity: torpedo heads loaded with a special “Torpex” mixture; landmines assembled in their scores of thousands; Sulphuric and Nitric acids being made and concentrated; gun-cotton (actually gun-paper, an aussie genius had discovered that eucalyptus fibre was just fine) mixed with nitro-glycerine to make cordite: cordite extruded into thousands of miles of coarse and sometimes hollow threads, to be chopped into lengths for processing in warm ovens; glycerine nitrated to nitro-glycerine - it gives you a fine headache! – made in 1-ton lots; it was slightly chilling to look at massive amounts of this sensitive material; and always the shell-filling, long rows going into the distance.

And lots more. It was well organized, and it worked. There were thousands of men and women in the factory, and my mind could not help but think that around the world there would be hundreds of similar plants only much bigger.

I should mention “burning –off”. This was a fenced area for disposal of waste explosives; almost all came from the cordite and gun-paper plants as scrap, floor sweepings, or out-of-spec material. These (but not detonating explosives) could be safely burned if not confined. For some reason, this area was under the control of the TNT day foreman, and from time to time he would announce “-burning off today”, and solemnly take out the key to the box marked “Matches” which would then be used to light a carefully-prepared fuse-train leading to the explosives. These would ignite in a spectacular burst of flame. One day he asked me to look at something which didn’t seem right; it was a round green-grey disk with a cheesy texture, about 2ft diameter, weighing about 100lbs. It certainly wasn’t right, and turned out to be the steamed-out charge of an unexploded Japanese bomb from Darwin; the chemist who emptied it had said in all innocence “— take it to the Burningoff Ground”. A few days later there was a general notice tightening the disposal of scrap and explosive waste. Interestingly, the material was an unusual explosive which reflected the Japanese lack of toluene.

During my first year, a handful of men passed through the unit for special training, and these (including my kiwi friend) were sent to Adelaide to start up the explosives section of a large ammunition factory. A similar plant was reputed to be under construction near Villawood, west of Sydney.

With time I seemed to become better known: senior men would nod and sometimes know my name, and I wondered if there was any chance of being selected to go to this new factory. In late 1942 this came true: I was told that I was destined to be the Chemist in Charge of the 100 ton-perweek TNT plant. So towards the end of 1942 Corinne and I, with little 7-month Helen, spent 2 months in Adelaide before going to Sydney.

In Adelaide I had the first inkling that the War was changing, and this needs some background. The basic assumption on which these great factories had been planned was that WW2 would be like WW1, with millions shells raining down in great artillery barrages, but for Australia at least, it didn’t work out that way. So when invited to look over one of the ammunition assembly plants, I was puzzled to see production at almost a token rate. From today’s viewpoint it’s easy to see the reasons: jungle warfare doesn’t call for lots of heavy ammunition; anyway the Americans were in charge and had their own dedicated massive supply lines; and above all, the terrible defeats on all fronts ceased by the end of 1942: although years of desperate fighting were yet to come, we had started to win.

All this was obscured in the future, of course, so I was puzzled. However, we did get a hint that basic explosives were still in short supply.

Just before Christmas 1942, we went to Sydney and I started work at the new explosives factory at Villawood. No slowdown there! Obviously there had been a slow start in the early war days, and someone was trying to make up for lost time. It had been planned on a big scale, several square miles bounded on the South by the Hume highway, on the West by Woodville road, reaching to Chester Hill and almost to the main waterpipes supplying Sydney. It certainly was a hive of construction industry; rumoured to be fifteen thousand men when I arrived. A severe drought didn’t help, causing water to be severely rationed.

Things proceeded at a headlong pace for several months, and everyone was looking forward to an early start of production. Then, almost imperceptibly, things started to slow down: engineers were moved to new projects; skilled tradesmen became scarce; morale of the awaiting production staff was dented. A late project was the sewer connection, and the unhygienic dunnies were a cause of problems. I went down with severe dysentery (yes, you sure lose lots of blood!). And so 1943 went by, and then even the early part of next year; it wasn’t until well into 1944 that we got going. My small team of chemist supervisors were so keen! We didn’t realize what was happening, and the penny didn’t drop until I was just assembling the staff (mostly women) for shift work, when a telegram came from the Department in Melbourne “DO NOT REPEAT NOT START SHIFT. CONTINUE DAY WORK ONLY”. So production crawled along at a snail pace: in fact we made no more than a thousand tons.

I realized why my proposal to increase capacity by 60% (it could have been so easily incorporated in the new plant at no cost) had not been adopted. We did have the new procedure for purification, and it was a great success. In fact it was the main reason why we had started at all: after the war I met a senior man from Melbourne headquarters who told me that a production-scale test was required, and we were it. Our quality was much superior to the American TNT being used at the shell-filling plants, and the purification loss was lower.

Since this is a personal record, I have to say that I was quite busy, despite the slow operating rate. Top-level managers were disappearing to new projects: later I learned they were planning new technology - - the war had ushered in many innovations, particularly for high explosives (RDX; spoken about in hushed voices), propellants and rockets. So rather to my surprise I was given a couple legs up the organization scale, and called on to take charge of the several square miles of many-faceted stores, magazines, maintenance shops and above all, the large acid factories, which fed the Explosives plant, and recycled its spent acid. Keeping all this going at a slow rate called for careful planning, in fact it was much more difficult than “going flat out”. The two raw materials were elemental sulphur which was burned and catalysed to make fuming sulphuric acid [105% strength - - I’ll leave you to work that one out] and aqueous ammonia which was recovered from Sydney’s gasworks, dehydrated and burned over a platinum catalyst to nitric acid. Juggling these two acids, concentrating, recycling and mixing them, was something I had to understand very quickly, but fortunately the man in charge was experienced and co-operative and we worked well together, particularly when the time came to close everything down. Until then, of course, and afterwards, the organization’s structure had to be maintained: telephones, transport, canteens, paymaster (v. imp!) and a million other items all needed attention. So I was busy indeed; firstly keeping things going, then closing them down in an ordered sequence.

It became obvious to everyone that closure was imminent, and by the end of 1944 the program to put the Acid and TNT plants on a “care & maintenance” basis was well on the way. Not a difficult program, merely attention to detail; no trace of TNT or acid must remain. But I merely set things on their way, for early in 1945 I left the Government service, and took a similar position with a Sydney chemical company which many years later became Union Carbide Australia.

Before leaving the Villawood area, I should mention an interesting incident. My boss in Melbourne warned me of an important visit due in a few days: everything had to be in good order. No, he couldn’t tell me what it was about - - just have things in good shape. I assumed it was an inspection team from the headquarters of Explosive Supply to see how the close-down was going, and prepared a summary of what was planned, what had been done and what had yet to be done. On the day, a group of men in civilian clothes arrived, escorted by the Boss from Melbourne: I must have looked as if I was aiming to join them, but the Boss cut me off & hissed in my ear “ - - it’s not for you; push off!”. So it was something secret, but you cannot beat the rumour mill; it turned out that the men were from the British Navy planning to bring the main fleet to the Pacific, and were looking for a site for a major store complex in the Sydney area. The rumour mill even knew that the decision was unfavourable!

Norman Stace, Perth, c.1959

There’s another little story. You will remember that I had been sent to Australia to work in the Australian munitions industry, and when word of my leaving the Government service reached New Zealand, someone there looked at the original agreement and called loudly and plaintively that “Stace must return to fulfill his obligations”. Sounded ominous! But I was determined to stay in Australia - - anyway, my new job-to-be was to take charge of a substantial complex which had been built to make the raw material for “explosives initiators” (which ensured that the detonator in a shell would in fact set off the TNT). Though not on Government land, everything had been built with Government money: it was a so-called Annexe, a device to use the resources of private industry. So I would still be working, both in fact and in spirit, in line with the original agreement. Someone in Wellington didn’t get the point, and telegrams flew to-and-fro across the Tasman, until a friend in Explosives Supply proposed I contact a Mr Nash, the NZ Technical Liaison officer in Melbourne. My advisor said “ - - his dad is the politician, Walter Nash”. So when I saw him, my story was ready “ - - We met some years ago :when I kicked a football from the Hutt High School into your backyard and you were kind enough to let me get it back” [quite true]. Of course, he didn’t remember, but it was a good start to the discussion, and he promised to “ - - sort Wellington out”, which he did promptly. And everything went through.

I tell this story for two reasons: firstly, it’s who you know rather than what you know and secondly, it’s why and how all five of you children were brought up in OZ and not in NZ.

The remainder of the War was spent as the supervisor of a most interesting complex, not too different in principle from the Villawood plant I had just left, but different enough in detail to make the job challenging. Originally built to make Dimethyl and Monoethyl Aniline (the first is the raw material for a high-explosive initiator, and the second is a chemical stabilizer for propellants), neither was being produced at the time: ample supply was available. However there was still demand for the intermediates, (aniline, nitrobenzene, nitric acid and ammonia), and as orders came through, the plants would be started, but at a low overall rate. Operating in this way demanded serious planning and new managing skills, but I took to it like a duck to water. The most interesting work was proposing to convert part of the plant to a new project.

Then came V-E Day, in August V-J Day; and that was the end of the War.

In summary, what had I personally achieved? Without boasting, I had gained a good name (probably better than deserved: I had the good luck to be the right man when senior positions became vacant), and I was seriously head-hunted by three Managing Directors seeking to create new industries in the post-war world. Also, I could have stayed in the Government munitions. All this, together with the feeling of general optimism in Australia, confirmed the decision not to return to New Zealand, and to stay (at first anyway) in Sydney.

And our family? At war’s end, Corinne and I had two wonderful, cheerful, lively toddlers and the third on the way. An achievement which puts in the shade my slight success in industry!

Pioneers of Tasmania & New Zealand

The Stace family were among the pioneers of Tasmania and New Zealand. Thomas Alfred Stace was born in England in 1780 and emigrated to Tasmania in 1824 with his wife Charlotte and children. The family emigrated again to New Zealand in 1853 with Thomas Alfred, Charlotte, their adult children (including Thomas Hollis Stace) and grandchildren (including Thomas Walter Stace).

Herbert Walter Stace

|

b. 26 Feb 1879 in Manawatu, New Zealand (to Thomas Walter Stace and Harriette Matilda Bannister) m. 1907 to Edith Catherine Peed Lived in Fiona Rd, Beecroft for around 13 years with his son Norman Stace and family Corinne, Helen, John, Peter, Brenda and Nigel. d. 30 Aug 1964 in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia (age 85) |

|

Thomas Walter Stace

b. 23 Dec 1850 in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia (to Thomas Hollis Stace and Amelia Sophia Lucas)

Emigrated to New Zealand 1853 (age 3) with his parents and grandfather

m. 31 Oct 1876 to Harriette Matilda Bannister in Wellington, New Zealand (age 26)

d. 07 Oct 1921 in Wellington, New Zealand (age 72)

The Stace family bible was a wedding gift from Charlotte Elizabeth Stace to her brother Thomas Walter Stace and his wife Harriette Matilda Bannister in 1876. It includes the marriage certificate and details about the birth of their children.

|

|

Register of Births

Amelia STACE was born at 8 o'clock on Thursday evening August 2nd 1877

Herbert Walter STACE was born on Wednesday February 26th 1879 at 8 o'clock PM

Mabel Jessie STACE was born on Saturday March 5th 1881 at 8 o'clock in the evening

Olive Martha STACE was born on Sunday December 17th 1882 at 1/2 past 1 o'clock AM

Myrtle Amelia STACE was born at half past 4 o'clock on Thursday night 20th November 1884

Linda Charlotte STACE was born at 1/2 past 4 on Saturday morning the 9th July 1887

Rita Marie STACE was born at 1/2 past 1 on Wednesday morning the 14th September 1892

Aileen Mary STACE was born on Thursday morning the 14th March 1895 at 9.30

Thomas Hollis Stace

|

b. 9 Jun 1820 in Camden, London, England (to Thomas Alfred Stace and Charlotte Sidney Hollis) Emigrated to Tasmania in 1824 (age 4) with his parents m. 20 Oct 1841 to Amelia Sophia Lucas, Pontville, Tasmania (age 21) Emigrated to New Zealand 1853 (age 33) aboard the schooner ‘Munford’ with three generations of his family including his father Thomas Alfred Stace (age 73), mother Charlotte (age 55); wife Amelia and their five children including son Thomas Walter Stace (age 3). Built house in Pauatahanui, Wellington, New Zealand. House is classified as a historic building. Also established a burial site at Pauatahanui. d. 29 Oct 1890 in Wellington, New Zealand (age 70) |

|

Thomas Alfred Stace

|

b. 1780 in England (to Thomas C Stace) Employed as Stationer and became a Freeman of London in 1807 (age 27) Travelled to France in 1816 – see passport m. 1819 to Charlotte Sidney Hollis in England (groom age 39, bride age 21) Emigrated to Tasmania 1824 (age 44) with his children including Thomas Hollis Stace (age 4) Built "Stace House" in Pontville, Tasmania which still stands Emigrated to New Zealand 1853 (age 73) with his three generations of his family including his wife Charlotte (age 55), son Thomas Hollis Stace (age 33) and grandson Thomas Walter Stace (age 3) d. 9 Aug 1866 in Wellington, New Zealand (age 86) |

|

Thomas Alfred Stace: Freeman of London, Stationer (1807); Passport to France (1816)

Copy of letter hand written in 1847 by Thomas Alfred Stace to his son Thomas Hollis Stace

Mr T Hollis Stace, North West Bay, Brown’s River [Tasmania]

Ouse Bridge 14 Jany 1847

My Dear Son,

I got home safe to New Norfolk on Monday 28 Decr & on the following Wednesday the 30th found 2 carts unloadg at the Wharf ready to take our goods up, we started about noon and stoped at the Wool-pack, Macquarie plains that night, where our carters kept it up nearly all night & consequently lost time in the morng so that we did not start till 8 o’clock, the time they promised to be at Hamilton. We did not reach our destination till after dark, when we had our bed carried over the bridge and slept in our quarters at the Chapel, the remainder of the goods were left in the carts and got wet by the rain next morng.

Fortunately the weather was dry the whole journey but very sultry, your mother stood the fatigue tolerably well & is now recovered from the effects of the journey. The worst part of the road is from the Wool-pack to Hamilton, it is almost impassable in places in wet weather, the latter part up & down a hill or two over a rocky plain like Brighton till you come to a mountain pass, where there is a descent round a deep bason by a (*?sliding) road which looks quite dangerous, at the foot of this you cross the Clyde at Hamilton, where we dined & were again detained by one of our drivers, but on the whole we cannot quarrel with them as they have not asked us for a shilling & send five of their children to school. --- Mr Martin being in difficulties could not keep his promise in carting up our goods, but as you perceive we did tolerably well. The sale of his chattles was to take place last week under the Insolvency, I am very sorry for him and trust he will still be able to struggle on.

Last Saturday I saw the Courier & had the gratification to find myself gazetted as Postmaster, on Monday I despatched my first mails. --- We find ourselves among friendly neighbours, our clergyman Mr Wright is a pleasant unassuming man, on Monday he examined the Children and discovered your mother to be a countrywoman of his & knows some of her friends, this will be no dis-service to us, he performs Divine service every Sunday. Our rooms are very small and it required some ingenuity to stow our things away. ---The Chapel is a neat gothic building standing on a stony rise facing the bridge, the Ouse rushes thru’ it over a bed of rocks. The land is mostly grazing but most of the flocks are now up the new country.

I date this on my birth-day, being born in A.D. 1780, and have consequently pass’d 67 years in this world, in this Island vicisitude has marked my course, what God in his providence may yet have in store for me either in weal or woe is shrouded in futurity. I desire to be thankfull for the good which (* two short words indecipherable) health has been given me and if disappointment and adversity has been my lot, it has been inflicted in mercy. Our steps are directed by the Almighty by paths we cannot see.

I hope this will find Amelia, yourself & the dear children in good health, this is an unhealthy time of the year for children, your mother would advise that they should have less coffee which is heating. Balm tea either hot or cold is very good for them.

Our love to all & kind respects to the Mr & Mrs Lucas’ families

Ever Yours Affectionately Thos A Stace

| This is a pleasant part of the Island, plenty of wood & excellent water, -- the great drawback is the distance from navigation and the markets. -- The licenced carriers take 4 days to the steamboat store & back, -- how wheat can pay I cannot tell, wool is a different thing. -- The bridge is not yet repaired, every thing has to be carried over and reloaded, the bullocks unyoked to go singly. We have a store or two near which is a great convenience. |

Thomas Alfred Stace: six-pence IOU, Hobart (1826) |

ANY DETAILS?!? PLEASE SEND / ADD INFORMATION

Norman’s paternal great grandmother, Amelia Sophia Stace (nee Lucas) was born in Hobart to Richard Lucas and Elizabeth Fawkner, both from pioneer families of Tasmania and Norfolk Island. Her grandfather Thomas Lucas (Norman’s great great grandfather) had been a marine on the First Fleet which landed in Sydney in 1788 and later emigrated to Norfolk Island and then Tasmania.

Her grandfather John Fawkner had been a jeweller in London before being convicted and transported to Tasmania. His wife Hannah Pascoe Fawkner paid her own passage to travel with children Elizabeth (Amelia Sophia’s mother) and John Pascoe Fawkner (Amelia Sophia’s uncle). John Pascoe Fawkner later went on to co-found the city of Melbourne.

Amelia Sophia Lucas

|

b. 9 Apr 1820 in Hobart Tasmania (to Richard Lucas and Elizabeth Fawkner) m. 20 Oct 1841 to Thomas Hollis Stace, Pontville, Tasmania (age 21) Emigrated to New Zealand 1853 (age 33) aboard the schooner ‘Munford’ with father-in-law Thomas Alfred Stace (age 73), mother-in-law Charlotte (age 55); husband Thomas Hollis Stace and five children. In 1869 received an inheritance from her uncle, John Pascoe Fawkner, who co-founded Melbourne with John Batman. d. 24 Dec 1894 in Wellington, New Zealand (age 74) |

|

Richard Lucas

b. 20 Dec 1794, Norfolk Island (to Thomas Lucas and Ann Howard). Born two months after his parents arrived in Norfolk Island.

Emigrated to Tasmania in 1808 (age 14). Family re-located as part of evacuation of Norfolk Island. m. 25 Jul 1821 (age 21) to Elizabeth Fawkner. She had two children by a previous marriage with Thomas Green. Her brother was John Pascoe Fawkner who co-founded Melbourne in 1835. Held 100 acres of land at Strangford, Tasmania d. Jan 1862 in a horse accident (age 68)

Thomas Lucas – First Fleet marine

b. 2 Oct 1760 in London, England (to John Lucas and Alice Catherine Westcott)

Became a Freemason in 1784, initiated into the Freemason Lodge of Temperance, London. His Masonic Apron is at the Freemason Lodge in Hobart.

Emigrated to Sydney in 1788 (age 28) as a Marine aboard the ‘Scarborough’ in the First Fleet.

Emigrated to Norfolk Island in 1794 (age 34) on the store ship ‘Daedalus’ with Ann Howard (a convict, not married) and their child Thomas. She had their second child two months later, just as her 7-year convict sentence expired.

m. 17 Aug 1801 to Ann Howard (age 40). They already had four children.

Emigrated to Hobart Tasmania in 1808 (age 48) aboard ship City of Edinburgh, in last group of settlers to leave Norfolk Island. Granted land at Brown’s River near Kingston, where they are recognized as the first settlers. Thomas Lucas had 530 acres, the largest holding in Van Diemen's land at the time.

d. 29 Aug 1815 (age 56) buried in St David’s Cemetery in Hobart. At his funeral the Masonic Lodge performed their ceremonies over him, as a brother mason.

Thomas Lucas: A marine on the First Fleet to settle Australia

Talk given by Mr. N.E. Stace in 1989 to the Northern Rivers (New South Wales) Chapter of the Australian Fellowship of First Fleeters

Thank you for the opportunity to tell the members of our Chapter something about my First Fleet Ancestor, Thomas Lucas.

My aim is to show how the lifetime of this man, born obscurely 230 years ago, reflected the great events which shaped the world we live in today. At the same time I will try to relate how Thomas made his way in the world.

Let us now look at the man: who was he?; who were his parents?; how was he brought up? Well, we have to admit we don’t know FOR SURE. There’s been a lot of research over the years, and still there is no hard evidence, no certificate linking his enlistment in the Marines with his parents, and so on.

However there is a lot of evidence to consider: for example his gravestone at St. David’s Park in Hobart in Tasmania:-

THOMAS LUCAS, a marine settler, who came from England with His Excellency, Governor Phillip, at the first forming of the Territory of New South Wales, Who died 29th August, 1815 (aged 56 years). ANN LUCAS, wife of the above, who died 10th June 1832; aged 74 years.

This puts his birth in 1759, and a survey of British records for that year (and also for 1760, since the marine records show 1760 for his birth year) has disclosed several tantalizing clues. He may have been the son of a Devonshire farmer, he could have come from Kent, or from Kingston-on-Thames, or from Plymouth.

I’m inclined, personally, to think none of these is correct: most probably, Thomas was born into a French Huguenot refugee colony, which had flooded into London about 70 years earlier. (In 1685 Louis XIV had revoked the Edict of Nantes, thereby stripping from French Protestants all civil and religious liberties. In the subsequent upheavals and massacres the survivors fled from France, many to England where their skills led to a rapid development of the textile industry).

On May 10 1758, Antoine Lucas, a bachelor, and Louisa Renoir, a spinster, were married at St Clement Dane’s Church by the curate Isaiah Jones. The witnesses were Gille Vivien and Thomas Ferrion.

Nine months and 14 days later, on 24 February 1759, Louisa was delivered of a son at the British Lying-in Hospital. She was 31 years old, and was discharged on March 22: it must have been a difficult birth to call for a stay of 4 weeks. The baby boy was baptized Thomas on February 25. I think he grew up to be my marine forefather.

I was informed some years ago, by one of his descendants, Miss Dulcie Lucas, a Hobart historian, that Thomas told his son that his father had been a silk merchant in London. The two had quarreled, and Thomas joined the Marines “....to see the world”. There is also evidence at the Hobart Masonic Temple of his mason’s apron dated back to four years before he left London. I think we have the right man.

The Thomas Lucas we know certainly had been well brought up. In Norfolk Island he was recorded (after his discharge) as a “painter and glazier”, and thus had been taught a trade before becoming a marine. Also at a time when many were illiterate, he could write. Many records exist of his firm clear signature.

Although his early years are not in clear focus, Thomas suddenly comes sharply into our view on Tuesday February 27 1787. On that day he was in a detachment of marines (1 captain, 2 lieutenants, 2 sergeants, 2 corporals, 26 privates and 1 drummer) which boarded the “Scarborough” transport . This ship of 420 tons was 5 years old, and was skippered by Captain John Marshall.

A few days later on March 4, 184 convicts were taken on board: subsequently the number was increased to 210. English jails were bursting, but the Fleet was not yet ready to go to New South Wales, and several months went by before it sailed on Saturday May 12, 1787.

|

Let us turn our attention, for a moment, away from our Thomas on the “Scarborough”, and look at the convoy of 11 tiny ships setting out from England to colonise an utterly unknown land, a whole new continent, 8 month’s voyage from home. On board were 568 male and 191 female convicts plus 13 children; 206 marines with 27 wives and 19 children; 20 officials and servants: a grand total of 1044 persons. Also there were about 300 ships’ crew who would return with their vessels. |

|

Looking back, we can only marvel at the sublime assurance, the self-confidence, the sheer barefaced gall of the British politicians and officials who conceived, planned and directed this enterprise. It’s quite clear they were sure of the outcome --- it would succeed, and succeed it did.

Back now to Thomas. He was one of a “mess”, a small group of 6 to 8 men who drew common rations which they prepared and ate together. We have an excellent record of this “mess”, as one member kept a daily diary, and at last we get a first glimpse of Thomas the man. It’s what the diary doesn’t say that gives us the clue: in the eight months’ voyage he was mentioned only once, having “..fallen down the aft hatchway”. He didn’t get the “stripes”(i.e. wasn’t flogged) for being drunk, for insolence, for theft, for fighting, for disobedience, for “unsoldier-like behavior”. Many others were. Thus we can say that our Tom was a wellbehaved and sensible man who kept out of trouble, who didn’t make enemies, and who went through the dull daily routines of watch-keeping and sentry duty, day and night for eight long months.

How dull it must have been! We today who fly to England in one day, and complain of even one hour’s delay, can have no idea of the deadly tedium of being cooped up in a tiny ship, with a hundred or more others. No wonder some of the marines misbehaved! But Thomas didn’t.

After the long slow voyage came the excitement of landing, first at Botany Bay and then at Sydney harbour, right where the city now stands. The fleet anchored at 6 in the evening on January 26 1788, now celebrated each year on Australia Day.

On shore the marines were camped in tents in two companies: Thomas was under the command of Captain Shea. Here we lose sight of him as an individual --- he is just another man in a scarlet uniform. Thus he would have been standing to attention at the first Church Parade on February 3, attended by all officers, marines and male convicts.

What was life like for a marine private in the first few years? The short answer is “Not very hard” Their commander Major Ross was adamant that the marines were not to be supervisors of convicts, but to be a guard against enemy attack. Thus we can see Thomas going through the time-passing routines which all soldiers use between wars: sentry duty day and night in wet weather and dry, polishing boots and buttons, cleaning weapons, daily parades, collecting rations and so on.

Exceptions were likely to be brutal and shocking, as when six marines broke into a food storehouse and were caught. The diary of a fellow marine records their hanging in simple, moving words.

However on June 3 1790 one event did have a happy ending. Seventeen months after landing, with food running desperately short, and no word from England, suddenly a sail was seen! It was the “Lady Juliana”, arriving after a ten-months voyage, bearing bad news and good: the bad news, a storeship the “Guardian” loaded with critically needed food and supplies had been lost after hitting an iceberg off the cape of Good Hope. The good news; on the “Lady Juliana” were 226 female convicts.

One of these was a spinster, Anne Howard, my great-great-great grandmother. Her crime? She was the nurse to the the wife of Mr John Reader of St Giles-in-the Fields, London, and had been found with “...a corded dimity petticoat (3 shillings), 2 muslin aprons (2 shillings each), and one child’s lace cap (10 pence)”. Tried at the old Bailey on 12 December1787, she was found guilty of stealing, and sentenced by Judge Recorder to seven years transportation. We shall see how the sentence changed her future life, and ultimately changed it for the better --- you can decide when you hear her story.

When she landed Anne would have been 28 or 29 years old: the records are confused. Indeed from her tombstone she may have been 32.

Thomas and Anne lived together unmarried, and on December 29, 1791 son was born, to be baptised Thomas by Reverend Richard Johnson.

The Norfolk Island connection

All this time, each marine had to face a decision: at the end of his term of service, should he return to England, or should he stay and receive a free grant of land? Initially, very few were prepared to accept discharge in the raw new colony, but as time went on more were willing to stay. Thomas could have returned at the end of 1792, but the records show that he decided to remain in Australia. In April 1792 he volunteered to join the “New South Wales Corps” as a corporal for a five year term, after which he would be given a free title for a farm.

This decision shows another aspect of Thomas’ character. He had a child, and his de facto wife had an unexpired sentence: many of his fellow marines thought nothing of deserting their women and children. But Thomas chose to stay: he was a loyal man..

In 1794 on September 26, Thomas, Ann and young Tom were shipped to Norfolk Island on the storeship “Daedelus” as part of a relief detachment. Eight days after sailing from Sydney, Ann and the boy were landed, but rough weather delayed unloading the soldiers for another week. Those of you who have been to Norfolk will know how difficult and dangerous landing can be, even today. There is no harbour, and open boats have to come over the coral reef through heavy surf.

In my mind I can see the little family, thankful to be reunited -- Thomas in his scarlet uniform, Ann 6 months pregnant, and the toddler young Thomas. I can see them walking together up the beach to their new home, the subtropical paradise of Norfolk Island.

On December 20 Ann gave birth to a fine boy I can say this because he is my great-great grandfather!). A few days earlier Ann’s 7-year sentence had expired, and she was no longer “subject to the Kings’ authority”. Thomas, of course was still a soldier and had to wait for another two and half years for his discharge. I’m sure they both looked forward to the magic date of April 6, 1797 for on that date he was to be paid off.

In passing, it’s interesting to note his last pay: for 103 days he received two pounds eleven shillings and sixpence, which equates to three shillings and sixpence a week, or sixpence a day. He was also granted 60 acres of land, and now we see another side of Thomas: he was a good farmer. I’ve actually stood on what was his farm; it’s rolling country close to the modern airport terminal.

Some of the discharged marines found their lives as independent farmers to be harder than they expected, but our Thomas did well and prospered. Many records exist of his selling wheat, maize and pork to the Government stores.

All this time, the two lived together unmarried, producing two more sons, making four in all. Each of these boys are shown in Norfolk Island records with the surname “Howard”, but this was sorted out, in a kind of way, when at last an ordained minister came to the island. And so on Monday August17, 1781 after a defacto relationship of 11 years and four sons, Thomas and Ann became legally wed.

|

The marriage register is interesting. It bears the groom’s usual clear strong signature (seen many times on receipts from Government stores); on the other hand, Ann and the two witnesses “made their marks” ie they couldn’t write. So Thomas, Ann and family settled into their life on this beautiful and fertile island, with its superb climate. I like to think their life was happy and peaceful. It was, for sure, full of hard fruitful work. However it had to come to an end, for the governments in Sydney and London decided to close down Norfolk Island, and to move everyone to the newly settled, much larger, island of Tasmania. |

|

| Right: Thomas Lucas and Ann Lucas (nee Howard) are honoured at St David’s Park, Hobart. |  |

Elizabeth Fawkner

b. 7 Feb 1795 in East London, England

Emigrated to Sydney, Australia in 1803 (age 8) when her father (John Fawkner) was indicted in

London for melting down stolen jewellery and transported for Life. Elizabeth, her brother (John Pascoe Fawkner) and mother (Hannah Pascoe) accompanied the voyage as free settlers on board the 'Calcutta'.

m. 1809 (age 14) to Tom Green (age 24) former convict, who had been transported on the same ship as Elizabeth and her parents. He died leaving her a 16-year old widow with two children (one of whom died shortly after)

m. 1816 (age 21) to Richard Lucas (age 21)

d. 23 Apr 1851 (age 56) in Hobart. Her brother ultimately became renown as the eminent politician and founder of Melbourne, John Pascoe Fawkner. He bequeathed part of his substantial estate to her children when he died in 1869.

John Pascoe Fawkner

|

Brother of Elizabeth Fawkner, uncle of Amelia Sophia Lucas. He bequeathed part of his substantial estate to her children when he died in 1869. He was only 5 foot 2 inches tall. b. 20 Oct 1792, in East London, England Emigrated to Hobart, Tasmania in 1803 (age 12) when her father (John Fawkner) was indicted in London for melting down stolen jewellery and transported for Life. His mother (Hannah Pascoe) and sister (Elizabeth Fawkner) accompanied the voyage as free settlers on board the 'Calcutta'. 1814 convicted of aiding convicts to escape. Sent to Newcastle for three years. m. 5 Dec 1822 (age 30) to Eliza Cobb. The Ceremony was said to have been performed in a Blacksmith's Shop with the anvil used to support the bible. |

|

Many convict ships brought with them the arrival of women in the Colonies and was cause for great excitement. Men rushed to the ships to choose a 'wife'. According to John’s memoirs one such ship arrived in Hobart on the 11th October 1818. Johnny was amongst the men waiting for the vessel to disembark its female cargo and he chose the handsomest girl on board. She was willingly accompanying him when they came upon another fellow who laughed at Johnny’s intentions, knocked the little man aside (he was only 5 foot 2”), walking off with the woman. Johnny strutted back to the ship and chose the homeliest looking girl onboard said to have had a pock marked face and a caste eye, Eliza Cobb.

She had been sentenced to 7 years transportation for kidnapping a four-month-old baby boy. At her trial it was stated that on apprehension she had told the constable that the child was her own. It is considered that Eliza in fact did have an infant child at that time and it had died. In her grief she had sought another to take its place.

|

Founded the 'Launceston Advertiser'. Obtained a license and built the 'Cornwall Hotel'. 1835 Purchased topsail schooner, Enterprize, which arrived in Port Philip 26 Aug 1835 – which was to be the future Melbourne. More info at www.enterprize.org.au d. 4 Sep 1869, buried at Carlton, Melbourne |

|

|

John Pascoe Fawkner and the ship Enterprize |

Hannah Pascoe

b. 1774 in Cornwall, England

m. 13 Jan 1792 to John Fawkner in Cripplegate, London

Children John Pascoe Fawkner and Elizabeth Fawkner

In 1801 her husband was convicted for melting down gold and silver from stolen jewellery. He was to be transported to Australia as a convict.

1803 Hannah was intent on keeping her family together and gained permission to travel on the same ship with her two children, John Pascoe Fawkner and Elizabeth Fawkner, as a 'free settler' together with several others who had also arranged passage on the 'Calcutta' [2nd voyage to the Colony]. Hannah was said [memoirs] to have been displeased with her allocated sleeping quarters and 'paid the boatswain Wyatt, 20 guineas for his cabin in the forecastle'.

Upon arriving at Sullivan Cove Hannah ‘was again not happy with her allocated accommodation especially in sharing a small tent with two other families and John built a rough hut.' 1806 Hannah undertook a three-year return trip to England, to claim her father’s inheritance. d. 7 Mar 1825 in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia

Harriette Matilda Bannister

Harriette Matilda Bannister (1853 – 1912) Herbert Walter Stace’s mother, Norman’s grandmother) was born in NZ, the third daughter of fourteen children of Edwin Bannister and Mary Tutchen.

Edwin Bannister

Edwin Bannister (1827 England – 1895 New Zealand) was Norman’s great grandfather. He was born in Dudley Castle in England. In 1840, when Edwin was 13 years old, his family travelled to New Zealand on the ship Bolton.[1]

He was secretary of the Order of Odd Fellows (Antipodean) in New Zealand for 28 years.

He was initially apprenticed to the New Zealand Gazette, and subsequently joined the Spectator and

Cook's Straits Guardian, the original Wellington newspaper; the Independent, and then the Evening Post. He continued on to the Government Printing Office, remaining there until he finally retired from active city life to his farm at Woodlawn, beyond Johnsonville.

He was survived by 40 grandchildren at the time of his funeral.

Mary Tutchen

Mary Tutchen (1829 England – 1917 New Zealand) was Norman’s great grandmother.

Bearing fourteen children with her husband Edwin Bannister, and living to the age of 87, Mary Tutchen was a pioneer of Wellington, New Zealand.

She arrived in New Zealand with her parents in 1841, age 12, aboard the Arab.[2] When they arrived there was no wharf or housing – the families lived aboard while the men built the wharf. They moved to Happy Valley, then Hawthorn Hill in Wellington, now named Tutchen Street. Her mother was Sarah Banger. The Banger family can be traced back to 1599 in Dorset, England.

Mary Tutchen (wife of Edwin Bannister), c1870 and c1913 3

William Bannister

Norman’s great grandfather

Edwin’s father William Bannister was manager of Lord Ward's estates – Limestone Works and Dudley Castle – for 30 years. He lived in a beautiful place called 'The Old Park'. The house was approached by a carriage drive lined with white and blue flowered lilacs. He was allowed a gig with two horses and two servants. When William's father died, the family convinced him to leave his position with Lord Ward to manage the Delph Clay Works (a family business). One or more of William's brothers did not cooperate with his running of the business and the business ran into trouble. He then went into the business of coal pits. When one of the coal pits being flooded William decided to emigrate to New Zealand.

William, his wife Mary Eades, and their three sons travelled from England to New Zealand on the ship Bolton in 1840.

The Bannister family can be traced to 1669 in Sussex, England.

Edith Catherine Peed

|

(1881 England - 1965 NZ) Norman’s mother Norman’s mother, Edith Catherine Peed (1881-1965), was born in London and moved to New Zealand at age 11 with her parents Edward Lightwood Peed and Susannah Steerwood, aboard the ship Tongariro. She passed her teacher’s exam at age 21, with a special mention for domestic economy. She lived to age 84. Her brother William Arthur Peed died age 28 in WWI and is buried at Damascus Commonwealth War Cemetery, Syria.4 Her sister Imogen died age 13 by accidental drowning. |

|

4 7th Australian Light Horse. Died of wounds 29th March, 1918

Edward Lightwood Peed

(1861 England -1938 NZ) Norman’s maternal grandfather.

Edward Lightwood Peed was a nurseryman and florist from Lambeth, Surrey in England. His father John Peed (1832-1901) was also a nurseryman / horticulturalist in Lambeth; while his grandfather Jonathon Peed (1791-1854) was a shepherd on Haling Park Farm.

1861 Census lists John Peed, Nurseryman & Seedman of Croydon (head), wife Elizabeth, and sons William G (age 5), Thomas (age 3) and Edward L (9 mo).

Notice of death for Jonathon Peed, shepherd and wife Sophia.

Susannah Steerwood

(1855 England – 1930 NZ) Norman’s maternal grandmother.

Edith’s mother was Susannah Steerwood also born in London. Susannah’s family was from Bethnal Green (inner East London) where her father John Matthew Steerwood (1822-1903) was a dyer. Both of Susannah’s parents, John Matthew Steerwood and Charlotte ‘Susan’ Nash, lived to around age 81.

b. 27 Dec 1915, Paignton, Devon England

m. 21 Dec 1940, Dunedin New Zealand, age 24 to Norman Stace

d. 14 Jun 2011, Hobart Australia, age 96. Buried at Pontville, Hobart Tasmania.

Corinne was born in the town of Paignton in Devon, southwest England, the youngest of seven children. It was just a month after the First World War had ended. By then her oldest sister Florence was 20 years old and would be married within two years in Sydney Australia. Oldest brother Arthur was 19 years old and a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Marines. Another brother, Theo, had died age 1 in 1902. There had then been a long break before another three daughters were born within five years of each other – Mary (May), Kathleen “Jean” and Corinne.

When she was 6 or 7 years old Corinne, her younger sisters and parents, emigrated to Australia. Her older sister Florence and brother Arthur had already emigrated to Australia and their parents decided to follow.

Over the next few years the family lived in country New South Wales, Tasmania, and Western Australia. Corinne spent her teenage years living in Nedlands in Perth, where she attended high school and the University of Western Australia while her parents continued to travel. Her sister Florence and brother John were living in Perth – John married in Perth in 1931 but later moved to Rhodesia. Florence had married in Sydney in 1920 but by 1936 she is recorded as living in Perth where she was a water-colour artist; later she moved to Nelson in New Zealand.

Around 1938, when Corinne was age 20 or 21, she moved with her parents to New Zealand where she started to study medicine at university. She met Norman in Dunedin and they married in December 1940.

Corinne Hall in Nedlands, Perth c. 1938

The following story was written by Norman Stace in 2003:

Norman remembers Corinne

Dearest Corinne -- a beautiful name! -- was born on 27 December 1915, in Paignton, Devonshire, England, the youngest of a family of seven children. Her parents were both born in London: her father was of Scottish descent, and her mother’s people came from Cheshire in the North of England.

In 1915 the First World War was raging, and her dad was in the British army in France. He survived; but the post-war years were full of uncertainty, and the family was restless, wondering where to raise their children; they spent brief periods in North Scotland, in England (Swanage), in Guernsey, in Cannes, France: all the time debating whether they should migrate to Canada or South Africa or Rhodesia, as other relatives had done. Her mother had a comfortable inheritance, and they could have gone anywhere ---- BUT WHERE?

The matter was resolved when a sad letter came from the eldest daughter who had married an Australian major with a wheat farm in Northern New South Wales; a disastrous fire had left them in terrible trouble. And so Australia it was to be.

Corinne would have been 6 or 7 when they arrived, and what a change Australia made! As a little child she had been pale and somewhat ailing with a perpetual runny nose and a handkerchief always pinned to her dress: wartime rationing in England could not have helped. But Australian food and sunshine and the open air wrought a transformation: she entered into the work on the farm with gusto; being the smallest, her job was to milk the cow, and to bring in the horses in from the great paddock. One of her much older brothers told me, many years later, of his memory of this little kid with a great big grin, riding the old draft mare, rounding up the horses for ploughing, singing and talking to them.

This is the Corinne we know; always doing more than her share of work, her easy empathy with animals, and who could overlook that happy smile!

Let’s go fast-forward fifteen years to 1940. Corinne had graduated Bachelor of Science, majoring in Geology and Zoology, subjects chosen from a love of learning, but not a source of income in the 1930’s Depression years. She learned the stand-by of secretarial and office work, but after a few years found this unsatisfying. So 1940 found Corinne at the medical school in Dunedin, New Zealand, with an aching heart from an unhappy love-affair, determined to let romance go by, and to concentrate on her aim of graduating with a second degree in Medicine.

Corinne and I had known each other for several years as casual acquaintances: we had many mutual friends but our paths didn’t often cross. But in 1940, I had a lucrative post-graduate fellowship based in Dunedin: we became friends, then good friends, then somehow, fell in love and decided to marry at the end of the year. So on December 21 1940 we were married at All Saints Church.

The war was raging, and not going well. It may seem strange that at such a terrible time we could even think of romance, let alone marriage; but we were in love, and that says it all. How the war changed her destiny, together with tens of millions of others!

Corinne was 24, soon to be 25. Let us now “fast forward’ and take snapshots at each 15 years of her life.

At 40, 1955 Corinne in Australia had come through the difficult postwar years, with truly primitive living conditions: but now she had a new house, with a civilised infrastructure. But not just a house, for by 1955 Corinne’s family was one thoughtful teenager, two ever-busy boys, and a cheerful 5 year old girl. Also for three years she had looked after her elderly, ailing father-in-law (my dad) and his care was to continue for ten years. Each day, 21 meals had to planned and prepared; housework, clothing, bedding, shoes and much much more had to be organised & done. Access to a car meant new horizons: diligent studies to become a most successful Scripture teacher for 6 or 7 lessons weekly at primary and secondary schools and each Sunday. In particular she was an active member of a committee initiating a new Anglican girl’s school in Parramatta --- today’s most successful Tara. This is just the briefest outline of what was done with unfailing love, care, and good humour.

Back: John, Helen, Peter. Front: Nigel, Corinne, Norman, Brenda

Fast forward now another 15 years to 1970; age 55. Even busier! One more in the family, by 1970 a 13-year old boy, making 5 children in all. The older four had grown up and finished their tertiary studies: two had married and two were working overseas. During this fifteen years, the family had become more complex; lots of coming and going; friends and friends of friends were always encouraged and welcomed. Corinne had made a beautiful cherishing home not only for her family but also for deeply treasured friends. Only I know of the unceasing love, and sheer hard work done so efficiently, so thoughtfully, so unobtrusively during this time of launching our family into the world.

In this period we began to greatly enjoy overseas holidays, a change from earlier years of pinch-penny vacations.

All this time Corinne continued her strong Christian work as a Scripture teacher, influencing generations of children in primary and secondary schools.

The next fifteen years, 1970 to 1985: age 70. This period was hall-marked by the arrival of grand-children, a pleasure which has to be experienced to understand its joy. Corinne, with a happy heart, did what was needed to make our grandchildren -- each one so different, and so lovable -- welcome at our home; and this bond has endured.

Corinne and Norman at Peter Stace’s wedding, 1974

Two other things stand out. In 1981 we spent three memorable months in Britain and

Europe, the first time since 1922 that she had visited the land of her birth. Also I retired in 1982, to buy a macadamia farm in Northern New South Wales. Once again, Corinne showed her home-making skills by creating a great little house, very practical, very welcoming, a delight to live in. We spent 18 years there: a most happy time for us both. Her warm, levelheaded and sincere personality created a circle of friends who we still treasure. Corinne maintained her strong commitment to Christian teaching, influencing new generations of pupils at local schools.

The end of the Nineteen Hundreds; 1986 to 2000 --- age 71 to 85. The happy time continued, working hard on our farm and travelling; but as the millennium approached we had to make a decision to retire. And so in 1999 we moved to Tasmania, which we have loved. The 2000’s. These years have seen us change from active and sprightly to elderly, but Corinne continued to show her art and skill in making a warm, welcoming household.

Tasmania and Tasmanians have been wonderful, far exceeding our very high expectations when we arrived here.

Each day I have looked at Corinne, and given a heartfelt prayer of thanks that such a wonderful person has been my wife, the mother of our children, and the grandmother of the second generation. God has been very kind to send such a blessing to this world.

|

Farm at Dorroughby, c.1986. Tom, Clare, Emily, Brenda, Norman, Roger, Sara, Peter, Corinne, Auvita |

The following story was written by Corinne Hall (Stace) in 2003:

If an expatriate Scots man or woman thinks sentimentally of home, he or she will probably think of the Highlands with its Glens and heather and the magical drone of the bagpipes.

For centuries the Highlander was a clansman deeply loyal to his chieftain and ready to answer his call when action was needed. Each Clan was a loosely knit group of folk of the same name and family bonded together by custom. For centuries there had been interchange across the Border between the Scots and the English, but after the Stuart Kings cemented the thrones of England and Scotland, the Highlanders chafed at the English presence.

It was the arrival of Bonnie Prince Charlie from exile in France in 1745 which aroused the national pride. The Prince secretly landed by boat on the West Coast not far from Fort William, and sounded the call to arms which brought many Highland clans to his side. His purpose was to oust the English and establish himself as king. His success was enormous and he led his army of Highlanders over the Border into England with little resistance, almost to the city of London itself. But the joy of success was shattered by the news that and English army of fresh soldiers had assembled at Inverness in the North of Scotland. The Prince had to march his weary troops back to meet the English at Culloden – just east of Inverness. The exhausted Highlanders were easily routed and many were slaughtered.

The battlefield exists to this day with a record of that dreadful encounter, but the sprit of the

Highlanders was shattered by what followed afterwards: The Prince escaped to France: the victorious commander forbade the use of Gaelic and the wearing of the tartan and insisted on the use of the English language: wholesale killing of rebellious families went on. A sad glom filed the mountains and the glens. Worse still, their own Chieftain chose to live a city life and put factors or Stewarts on their estates to collect rents from the crofters, a notion quite foreign to the peasant’s farmers who had always claimed their small holdings as their own. Life became intolerable and many a crofter who once grew his own food for his family could no longer survive. SO became the emptying of the Highlands. Poverty and starvation drove them to seek a life beyond the seas and many went to Novia Scotia, Canada, Australia and New Zealand where their native ability and persistent endeavour laid down valuable foundations in Education and Industry in these colonies.

But although many thousands of Scots left their homeland they didn’t all migrate beyond the seas. A wonderful flowering of scholarship and invention enabled many Scottish minds to usher in the enormous success of the Industrial Revolution. Once every village home had its loom where weavers spent his day making cloth of wool, now it was done at factories along with the weaving of cotton and linen imported from Ireland and America. So creating the great textile factories of Paisley and Peebles not far from the wealthy city of Glasgow. To aid the steam powered machinery the necessary coal was not far away particularly along the upper Clyde Valley around Lanark as well as other places. Coal pit owners mercilessly worked the miners and their families under shameful conditions and pay. Once a man joined a coal pit he was indentured for life and was refused permission to seek work elsewhere. Finally ship building along the Clyde brought workers to congregate around the Glasgow area which son spread outwards and westwards to incorporate villages. One such village was Johnston where we met our ancestor James Hall.

“Were you born in Scotland?” I once asked my father. I was curious because he used to wear a tartan tie and would take long walks in the Highlands.

James HALL, says genealogist Mr Simon HALL of Canberra, was born in 1795 in Johnsonville, a hamlet west of Paisley in Renfrewshire in Scotland. He kept a grocers shop in Johnsonville, but his customers were not wealthy people, but probably weavers and workers in the textile and woollen industry whose main needs were oatmeal, salt and beer with very few luxuries which they couldn’t afford.

James being a frugal man himself may not have wanted much more, that is until he met Margaret BARR of similar age as himself.

Margaret was a lass from Paisley: she was bonnie and strong with a cheerfulness which could bring a smile of joy from James. She was little more than eighteen years old when she and James were married at a small church at Kelbarchan, not far from Johnsville. The two set about reviving and improving the grocery shop. Margaret was always full of ideas: James was the patient worker who great full put Margaret’s innovations in to effect.

Children came along. First there was Janet, then Sarah. Then a son James, who was so sickly and poorly that Margaret hastened back to her girlhood parish of Paisley Abbey to seek baptism for her dying baby. Their next son prospered: he was also called James, born in 1827.

But death was never far away in those weary and impoverished times. Little Sarah died at the age of six. The baby, William Barr Hall was only a few months old when Margaret, watching her husband working at the shop, saw him suddenly collapse on the floor. She screamed “my husband has been struck down by God”. Neighbours rushed in and carried the poor man to his bed. A doctor was called, but it was too late. James Hall had died of a stroke. There is a grave stone in the Paisley Abbey cemetery marking his grave. It says “James HALL husband of Margaret Barr Hall and father of daughter aged six” (Someone is forgetting his other children? Bre) He was thirty five years old.

Margaret was left with three children to care for: Janet, promising young lass of seven or eight; little James two or three years, and baby William just a few months old. Then there was the grocery shop which was Margaret’s only source of income.

She closed the shop for a few days whilst she reorganized her routines with the children, but she needn't to worry. Little Janet at eight years took control of the nursery; she laughed and played with toddler James and could even hold the feeding bottle for baby William.

Back in the shop, Margaret did her best to carry on as James had done but she soon found that she was losing customers because she closed at six pm. instead of the usual seven pm. The money in the till seemed to shrink whilst the debts grew. The worst moment came when an overdue amount came from her supplier, Robert Miller, Wholesale Provisioner. Margaret wrote a pleading note for an extension of credit: she would work harder – she wrote; she apologized for the delay in paying. Work harder she did, but she couldn’t make up the areas.

After several months a young man appeared at the shop. He politely introduced himself as Robert Miler Junior. He inquired about her problems, her children and her business. He listened patiently and when she had finished he said “Mrs Hall, my father and I are very sorry to find you in such distress: will you allow me to help you re-organize your management so that together we can get your business working profitably?” For nearly a year, young Robert Miller spent Fridays afternoons checking her shelves and re-ordering needed stock and canceling orders for unpopular items which working class Scots seldom use. He seemed to enjoy the weekly visits and although he was strictly business-like and rarely allowed any unprofessional warmth to change his countenance, Margaret began to look forward to his visits. She felt the pleasure of the improved business under her own name and she liked the candor and Robert’s very occasional smile. After a time, Robert told her that his father wished to retire from business and he wanted Robert to take over as manager of the firm.

“Why don’t we make a team together?” he told her, “you sell the shop and join with me as Grocery

Provisioners. That way we can make a home for the dear children and you will be my beloved wife!” Margaret accepted. This time Margaret’s trip to Paisley Abbey was a happy one – she entered as Margaret HALL and came away as Margaret Barr Millar. It was 1832, and she was 37 years old.

Margaret strove to bring up the children nicely and to assist Robert in the business. He was now calling himself Provisions Merchant and he dealt in wholesale goods which required a storehouse instead of a shop and his customers just like the ones James Hall had provided. For more than ten years they worked the Paisley district supplying the little grocery shops but their returns were sometimes marginal. By this time Margaret had developed a god business head and she saw that people of the Border Country, especially in Ranfurly Shire were factory workers with very basic needs and unlikely to buy the luxury goods which carry higher profits. She also observed that many business folks were moving away from the Boarder for places in England where life was possibly easier. So she discussed with Robert the idea of re-locating to London as many Scots had already done. At first Robert was aghast – leave Scotland, the land of his birth! NEVER. But his god sense prevailed as all good Scots do, and they began to plan to reopen a warehouse near the River Thames with the idea of supplying food for the multitudes of refugees swarming into England from the Continent. These people were escaping religious persecution in their home countries because the

Edict of Nantes had been rescinded which had previously allowed religious freedom. There were Huguenots from France, silk weavers and dyers from Flanders and Belgium, Jews with their black hats and curly whiskers and their propensity to be associated with finance, all gathering around the docks along the Thames. On the dirty waters of the river Thames, coal lighters bringing coal from the Clyde river Valley or coal pits of Newcastle kept gangs of noisy men carting their coal all over London – the sot smearing the walls of windows and walls of houses and public buildings a dirty grey.

The Robert Miller Wholesale business opened at Tower Hill where the East end of London spread out into the cramped little hovels of Stephney, Spitalfield and Whitechapel.

Margaret chose to live there. She looked around the newly developed suburban land of Lewisham on the South Side of the River. She found a villa where she felt she could provide a real home for her Robert, her beautiful young Janet and her two growing sons James and William. Robert later sought a new location nearer the heart of London and found premises at Tolley Street on the South side of London Bridge. Here he would supply the grocers for wealthy Surrey patrons who had a taste for sweet butter and fine chesses. He realized his need to know more about the growing trade with the Irish dairy importers. One trader’s name of prominence was “Pontifex and Woods” Robert sought Margaret’s help in getting to know more about these people.

It wasn’t hard, for the Woods family also lived at Lewisham: their teenage sons and one daughter were of similar age as Margaret’s children and the two families became friendly. The young Woods boys had ambitions of seeking African adventures in the South African provinces of Natal and told dazzling stories of wealth farming tobacco under the hot African sun using black labour. But James and William Hall’s future was with the wholesale provisions business because Robert was teaching them the trade and was preparing to take them into partnership as Miler and Halls. Also, James Hall had fallen in love with the beautiful daughter Anne Woods and he was eager to marry her.

And so the marriage of Miss Annie Woods, daughter of the late Mr. & Mrs. James Woods’s son of the late James Hall & Mrs. Hall was arranged.

Anne’s mother had been Miss Pontiface.

Margaret was sad that her son’s father, James Hall was not there to see his son James married but young William ably supported his brother at the ceremony and Margaret felt glad of that. She watched the beautiful young 18 year old bride serenely make her marriage vows at the Baptist chapel in Denmark Place, Lambeth.

It was the first of June, 1859 – a glorious sunny day to start a glorious new venture.

Margaret was apprehensive about the idea of James and Anne taking up an agency in Ireland to buy butter, cheese and other farm products for the firm Millar and Halls. She was going to miss him; her only surviving daughter, Janet had married a young man from Renfrewshire by the name of Barr.

Probably no relation as it was a very common name in those parts, and now lived in Scotland. William was still living at home in Forest Hill, working with Robert at Tolley St Warehouse. They were excited about leasing part of the Haberneum wharf where the little packet steamers plying from Sligo in Ireland to London would unload the butter and cheese. Business was picking up and everyone was enlivened by success.

James and Anne – now known as Annie remained in Sligo for six years where four of their eleven children were born. Robert and William kept the London business going but sometime in 1861 Robert died leaving William to manage on his own. It wasn’t until the mid-sixties that James and Annie returned to London when once again the two brothers worked from the same premises. Both men sought more rural outlook to build their homes and moves south of the river to the district of Coulsden. James felt the importance of a business man to need a fine house so he built a fine mansion which he called “LISADEL” after a house by the same design he had admired in Ireland. Here his eleven children enjoyed semi-country living. Family legend has it that during the development of the site for the garden, a shipment of tinned meat was found to be contaminated and was condemned. Not put out, James ordered that the tined meat to be laid for his future carriage way. Unfortunately James died in 1882. His young family was still growing up so Annie was forced to sell Lisadel as her husband had left very little money. The mansion still stands – for a while it was part of the Croydon Council Chambers; later it was converted to four high class flats. Simon Hall and his father Richard Hall visited the house in the mid 1970 1980’s and photographed it from many aspects.