German and British and American technology

(this chapter is for techno-nerds)

We of British heritage all know that the UK has won more Nobel prizes in physics and chemistry per capita than any other country.

But Germany comes in a close second, well ahead of the United States per capita (nevertheless, with four times the population of Germany, the US has many more medals in every category than Britain, Germany and France combined).

The Deutsches Technikmuseum in Berlin vaunts the many world leading German contributions to science, inventions and technological developments beginning with chemistry and progressing through mechanics to biology. One only has to think of Albert Einstein. In the Technikmuseum we can see advances in dyes and explosives as well as internal combustion engines like the contributions of Rudolf Diesel, Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler; ramjets; rockets and gas turbines.

Many parallel British advances, like the gas turbine, that one can see in the Science Museum in London.

Although the British inventor Frank Whittle is credited with the first practical gas turbine, a German aircraft the Heinkel He 178 was the first turbojet to fly, based on an engine independently developed by Hans von Ohain. Anselm Franz at Junkers (German) resolved some early design difficulties and the Messerschmitt Me 262 became the world's first operational jet-fighter aircraft, some months ahead of the British Gloster Meteor. Modern aircraft engines incorporate both British and German contributions.

Beuth steam locomotive with a revolutionary steam valving arrangement;

a German gas turbine aircraft engine (above) with a modern type below;

one of 31 German Nobel Prizes in Chemistry - this one for reproductive steroids and the birth control pill;

V1 Rockets (early cruise missiles or drones) - the V2 (not shown) became the basis for the US Space Program

So when my electrical and electronics engineer father had told me that the British invented radar I was inclined to believe him. And it's true to a degree.

The British built a series of radio detection and ranging (RADAR) stations along the coast facing Europe and these were instrumental in detecting attacking German aircraft early enough to 'scramble' fighter pilots, including my father. This enabled them to 'bring down' German bombers in sufficient numbers to make them give up and stop coming. So that's what the acronym 'RADAR' originally referred to, a British invention. But that's not what the word came to mean.

The original British RADAR worked in the normal radio spectrum by triangulation, as do GPS location devices today (in the microwave spectrum), partly by detecting variation in pulses sent out and partly by listening to the aircraft's own radio transmissions.

The German system, invented before the first British system, was based on the way a bat navigates by listening to echoes of ultrasonic beeps it sends out like SONAR. Thus, in development, it was called Elektroakustische Apparate (electroacoustic apparatus). It worked by illuminating a possible target area with rapid pulses of radio radiation the 50 cm band (560 MHz) and timing their reflection. It came to be referred to as: Funkmessgerät (radio measuring device) or FuSE.

Modern radar works the same way, by timing (and analysing frequency changes) in the reflection of a signal previously sent from the same device.

The principle was well known and physicists in several countries were experimenting but to reach the ultra high radio frequencies required for a practical device novel technology was required. A German, H E Hollmann was first to patent a cavity magnetron capable of reaching microwave frequencies in 1935. But it was unstable so the Germans electronics engineers developed the klystron, patented by Irish/American engineers Russell and Sigurd Varian in 1937, to achieve the frequencies needed for their advanced radar systems.

Meanwhile in 1940 at the University of Birmingham John Randall and Harry Boot had never seen a magnetron and had no preconceived ideas but set a goal of finding: 'a microwave source giving one kilowatt on a ten centimetres wavelength'. They quickly settled on a new type of cavity magnetron that made radar practical at much shorter wavelengths and with higher power than the German device.

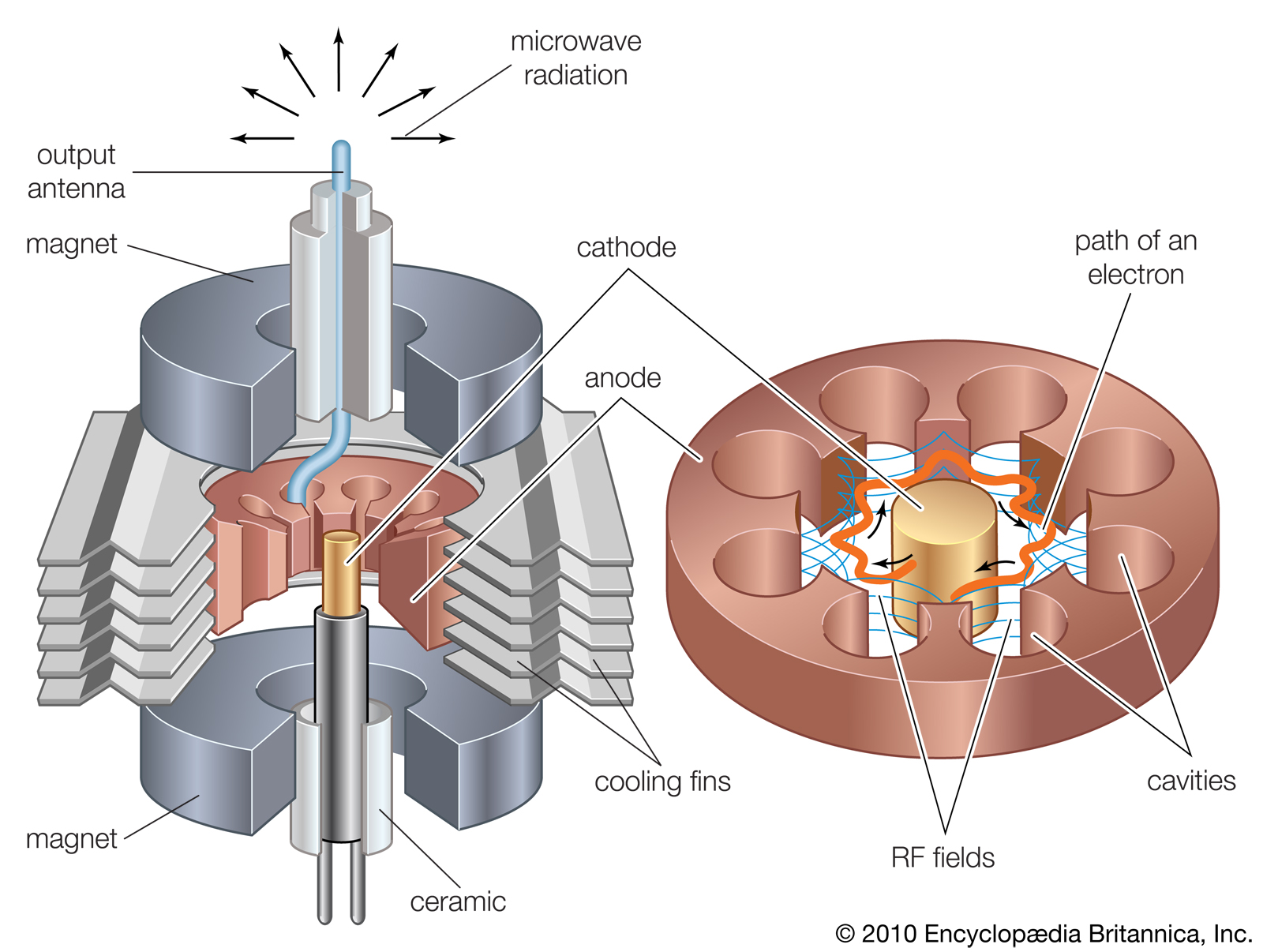

The anode block - key to the cavity magnetron developed by John Randall and Harry Boot in 1940 at the University of Birmingham.

Microwaves are a surface effect so each hole is in effect a separate one loop coil or resonator

A central cathode is suspended down the axis and powerful magnets cause emitted electrons to

spiral on their way to the anode causing the cavities to resonate - like blowing across a bottle

(obviously the cavity needs to be evacuated - like any radio tube)

Science Museum London / Science and Society Picture Library - Original cavity magnetron, 1940

Shorter was better. It allowed smaller dishes (antenna) and detection of much smaller objects. Their secret was subsequently shared with the US and development work continued at MIT. The secret was also shared with the Varian brothers who set up to develop advanced radar and microwave communications systems in a schoolhouse on the campus of Stanford University in California. This was the genesis of the Stanford Technology Park and the seed that grew into Silicone Valley. A different story. Interestingly, Russian physicists, N F Alekseev and D D Maliarov, had also designed an improved magnetron but Stalin, like Hitler, was a science illiterate (both had won divinity prizes at school) and unbelievably the leading Russian radio scientists were purged. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) publishes a paper: The Cavity Magnetron: Not Just a British Invention in its Historical Corner for those who would like to know more.

|

|

The original schematic of the GEC magnetron Type 1189 and microwave oven magnetron

IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, Vol. 55, No. 5, October 2013 and Encyclopaedia Britannica

Today high power cavity magnetrons are produced in the millions and their mode of operation is no longer a secret. These typically produce from 750W to 1200W, much lower power than military radar. But these magnetrons are not for radar but for microwave ovens. In ovens the microwave frequency chosen is a resonant frequency with water molecules that thus readily absorb the radiation and heat your food. This is not a great wavelength for radar as there's lots of energy absorbing water in the atmosphere.

There's an urban myth that the cooking effect was discovered accidently when soldiers or ground crew stood in a 10 or 20 kW radar beam. There's no warning because we have few nerves capable of sensing internal burns so microwave radiation is painless. But the victims were blinded when their eyes were cooked from inside or if exposed for longer, made idiots when their brains were cooked.

This was the original 1950's 'death ray' and it's the source of concern about the excessive use of mobile phones close to ones head. Some have suggested that microwaves would be a good way to beam down energy from large solar energy collectors in orbit. Evil baddies eat your heart out.

Nevertheless provided your microwave oven door is undamaged it's quite safe when you heat your dinner. Obviously there's no residual radiation (except heat) left by radio frequencies that have wavelengths a lot longer than visible light (or shining a light on it would make food radioactive). But NEVER power-up a microwave oven with a broken door.

As you eat your nicely cooked vegetables you can thank those weapons engineers on both sides for just one of many useful 'spinoffs' from their inventiveness.

The history of radar had another twist. Microwaves turned out to be a great improvement on conventional radio for telephone communications and that's why you see those microwave dishes on towers all over the countryside. And it's thanks to the Varian brothers and a German/Swiss named Schottky, that we have the semiconductor devices developed in Silicone Valley, at Fairchild and other places, that most low power radar systems, that open our doors and tell us if we are speeding, now employ. But similar components now provide us with the UHF and microwave communications that enable your mobile phone, WiFi and Bluetooth devices to exist.

Anyway, the gist is that my father was mistaken. The Germans had modern radar before the British. But unlike the British and Americans they failed to perceive its value as a weapon of attack. It was not considered worthy of development expenditure beyond defensive applications, like gun aiming on Flak Towers, where two systems (Kulmbach and Marbach) worked in tandem at 10 cm wavelengths. Eventually captured allied magnetrons revealed their secret, allowing the wavelengths to be shortened further, but it was too late to put these into production.

Nevertheless even the German 10cm radar was very impressive. It allowed the big guns to bring down high-flying bombers at the limit of their range. Using radar and tracking computers the guns were successfully aimed up to two miles ahead of the attacking bombers and the shells were set to explode at their exact height. Planes that frequently changed height avoided the Flak but bomb aimers probably missed their targets as a result.

Collectively the Berlin defences, guns and aircraft, brought down 492 British bombers and damaged a further 954. 'Bomber' Harris, the British Air Marshal, then diverted his attention to easier targets. Later the US Eighth Air Force lost 143 bombers and 29 fighters in just three raids.