Preface:

The Craft is an e-novel about Witchcraft in a future setting. It's a prequel to my dystopian novella: The Cloud: set in the the last half of the 21st century - after The Great Famine.

As I was writing The Cloud, I imagined that in fifty years the great bulk of the population will rely on their Virtual Personal Assistant (VPA), hosted in The Cloud, evolved from the primitive Siri and Cortana assistants available today. Owners will name their VPA and give him or her a personalised appearance, when viewed on a screen or in virtual-reality.

VPAs have obviated the need for most people to be able to read or write or to be numerate. If a text or sum is within view of a Cloud-connected camera, one can simply ask your VPA who will tell you what it says or means in your own language, explaining any difficult concepts by reference to the Central Encyclopaedia.

The potential to give the assistant multi-dimensional appearance and a virtual, interactive, body suggested the evolution of the: 'Sexy Business Assistant'. Employing all the resources of the Cloud, these would be super-smart and enhance the owner's business careers. Yet they are insidiously malicious, bankrupting their owners and causing their deaths before evaporating in a sea of bits. But who or what could be responsible? Witches?

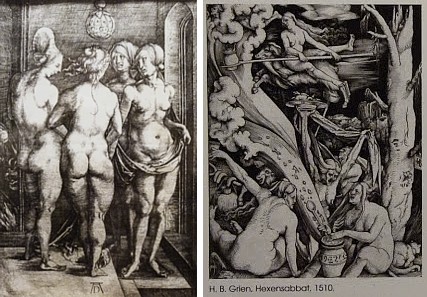

We were travelling through Rothenberg, in Germany, as I was putting my thoughts together. Serendipitously, to mark 500 years since Martin Luther nailed his '95 theses' to a church door in Wittenberg, setting in motion the Protestant Reformation, the Museum of Medieval Crime had an exhibition around Martin Luther's preoccupation with witches.

In the Early Modern Period witches became feared by Catholics and Protestants alike, as agents of Satan.

Jews and Christians and Muslims have long been warned against witches:

- A man also or woman that hath a familiar spirit, or that is a wizard, shall surely be put to death: they shall stone them with stones: their blood [shall be] upon them. Leviticus 20:27

- Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live. Exodus 22:18

Yet early Christians downplayed witchcraft as pagan superstition. But the Renaissance brought changes in theology. If God was benign, how could one explain the presence of evil and suffering?

Christians now feared that Satan, the Devil, was secretly at work through subversive human agents: witches (hexen).

Satan was believed to exploit original sin: mankind's base desires and weaknesses, in particular sex. There was also increasing alarm caused by new scientific discoveries and witches were thought to possess secret knowledge about nature and the universe.

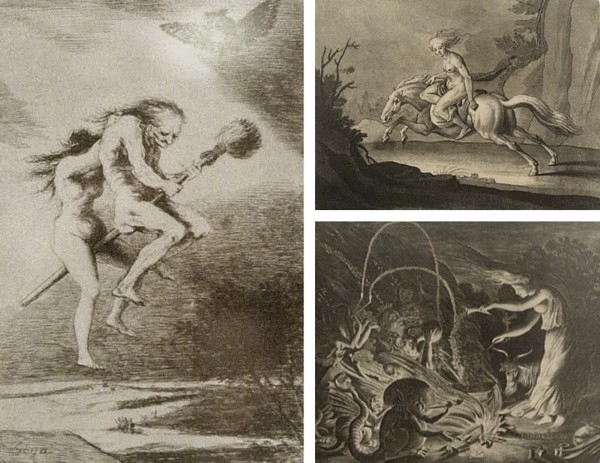

Regular outbreaks of the plague reinforced this belief. Surely each pandemic was the work of Satanic worshipers on broomsticks or riding a pale horse; it could not be the work of a loving God?

From their pulpits the clergy sounded the warning and across Europe somewhere between 40 and 60 thousand suspect women were dragged from their homes by terrified fellow citizens and sent to mock-trials; before being hanged or burnt alive.

Witches could be bewitchingly seductive: exploiting the basest desires in others. Others lurked alone or in covens, with other wicked women, and used 'dark arts' to cause illness and death in those that they chose as victims.

Thus, the depictions of witches, in the new medium of printing, were frequently highly sexualised: not as pornography but to illustrate their potential to bewitch and seduce, as a warning.

As the Enlightenment took hold, rationality and the scientific perception pushed back. Witchcraft became just another religion, no longer feared, and for most of us became the stuff of fairy-tales or Roald Dahl tales for our children:

|

A Note about Witches In fairy-tales, witches always wear silly black hats and black cloaks, and they ride on broomsticks. Roald Dahl - The Witches |

In my dystopian world of The Cloud, religion has gained new importance to offer some meaning in a benign welfare-society: without countries; or war; or shortage; or serious pain; where life is about consumption until one commits voluntary euthanasia. But power over others remains a human desire and some have turned to a new: Scientific Witchcraft to satisfy that need. Others, capriciously and amorally exploit The Cloud itself for casual amusement.

Warning: Like a Martin Luther sermon: The Craft has some strong adult content.

| As with all fiction on this Website stories evolve from time-to-time. Unlike printed books that have distinct editions, these stories morph and twist, so that returning to them after a period, may provide a new experience. |