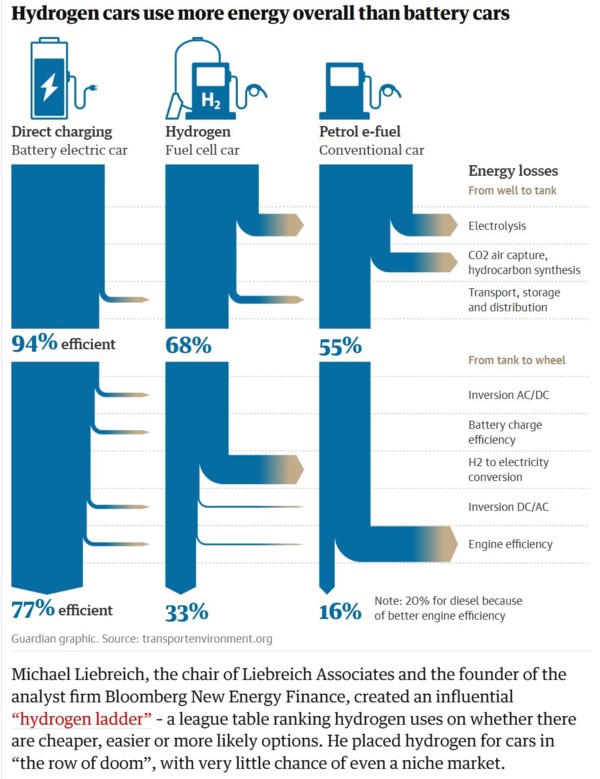

As anyone who has followed my website knows, I'm not a fan of using 'Green Hydrogen' (created by the electrolysis of water - using electricity) to generate electricity.

I've nothing against hydrogen. It's the most abundant element in the universe. And I'm very fond of water (hydrogen oxide or more pedantically: dihydrogen monoxide). It's just that there is seldom a sensible justification for wasting most of one's electrical energy by converting it to hydrogen and then back to electricity again.

I've made the argument against the electrolysis (green) route several times since launching this website fifteen years ago; largely to deaf ears.

The exception made in the main article (linked below) is where a generator has a periodic large unusable surpluses in an environment unsuitable for batteries. In the past various solutions have been attempted like heat storage in molten salt. But where there is a plentiful fresh water supply, producing hydrogen for later electricity generation is another option. Also see: How does electricity work? - Approaches to Electricity Storage

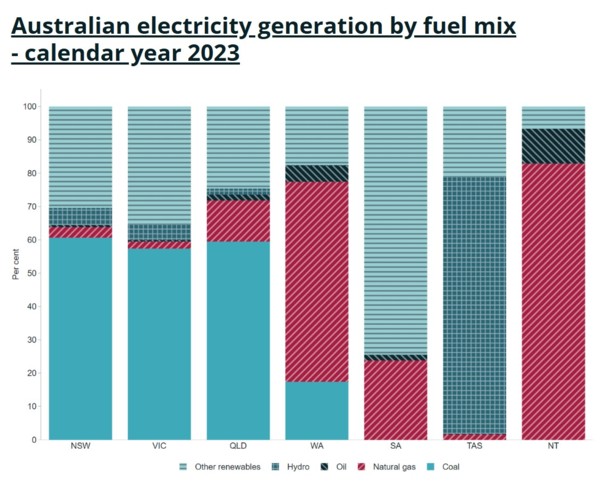

Two of these conditions apply in South Australia that frequently has excess electricity (see the proportion of non-hydro renewables chart below). The State Government, with unspecified encouragement from the Prime Minister and the Commonwealth, has offered A$593m to a private consortium to build a 200MW, 100t hydrogen storage at Whyalla. Yet, the State already has some very large batteries, with which this facility is unlikely to be able to compete commercially. Time will tell.

Of course, I've not been not alone in my scepticism. Numerous engineers and scientists have made similar points. For example:

Will hydrogen overtake batteries in the race for zero-emission cars? in The Guardian

A rare exception might be when an electricity generator (for example an off-shore wind or solar farm) has both ample water and a frequent surplus of (negative value) electricity, yet no practical way of installing a battery.

Worldwide, politicians play fast and loose with reality. So, we are assured, that hydrogen will be the mainstay of the Australian economy - when we are eventually obliged to stop digging up coal and shipping, over three quarters of it, overseas to be burnt, out of sight, out of mind.

The principal prophet of 'Green Hydrogen' has been billionaire: Andrew (Twiggy) Forrest, former CEO of Fortescue Metals Group, with other interests in mining and cattle stations. Twiggy is Australia's richest man and a larger-than-life presence (with a PhD in Marine Ecology). So, he speaks: 'truth to power'.

One acolyte has been Anthony Norman Albanese (Albo), the present Prime Minister of Australia, who likes rich men (but is not so keen on our richest woman). Since his days in Young Labor in the 1980's, Albo has been a strong opponent of nuclear generated electricity and was instrumental in having a ban on nuclear power becoming entrenched Labor Party policy. Yet, recently, he made an exception when it came to acquiring nuclear weapons (submarines - not bombs - so far).

So, he has been quick to embrace any competing form of renewable energy that might obviate the obvious need for peaceful nuclear energy and seems to believe that 'green hydrogen' is one such.

But Twiggy is first and foremost a businessman. He may have been misinformed but he's not stupid. So, this year (2024) his goal to have the Fortescue mines decarburise by 2030 was put to the test with a fair trial of both hydrogen and battery powered trucks (using solar and wind generated electricity).

At last I feel a little vindicated.

On September 25th, just in time for my birthday, Fortescue rejected their problematic hydrogen plan and placed a US$2.8bn order for electric mining equipment and vehicles, including 360 autonomous battery-electric trucks, from Liebherr.

See the main article: The Hydrogen Economy

Footnote

Hydrogen Powered Cars- known in the trade as 'fuel-cell electric vehicles' (FCEV).

In Australia an enthusiast has been able to buy a hydrogen powered car for years. The Hyundai Nexo and Toyota Mirai have been available since 2018.

But there is a catch if you want to drive them any distance. Due to the cost of compressing, and difficulties in transporting and storing hydrogen safely, filling stations are few and far between and hydrogen is very expensive - several times the price of equivalent petroleum based fuel (like LPG). One has to be very committed, even if able to afford an FCEV.

For example, The Toyota Mirai is currently only available in limited numbers for business fleet to lease on trial. There is only one Toyota owned hydrogen refueller (in Altona, Victoria) but there is also a filling station in Canberra and possibly others (you can look that up, if interested).

Both cars are electric hybrids - with the fuel-cell feeding the battery.

There is an interesting comparison of the cars in CarsGuide.com: Toyota Mirai vs Hyundai Nexo - Exclusive world-first comparison review of Australia's only hydrogen fuel cell cars

As the article notes: "The Honda Clarity, which was the only other mass production FCEV was recently discontinued, and previous experimental models by Mercedes-Benz, Ford, Nissan, and General Motors ended their runs many years ago."

It is important to note that the hydrogen in use is anything but free, as suggested in the article (presumably Canberra rate payers are copping that bill) and that it is not 'green'. Commercially available hydrogen in Australia is presently almost 100% 'blue' and has a higher 'carbon footprint' than LPG.

It's nowhere near: 'environmentally friendly'. Adding a whiff of more expensive hydrogen, generated by electrolysis, doesn't make it all 'green'. Just as the power from the grid, currently going to electric cars, is mostly derived from fossil fuels:

source: Energy.gov.au

(Ignore SA and TAS (mostly hydro - Bob Brown regardless). They are less than 7% and 5% (respectively) of the National Electricity Market and are supported by base-load links to and from from Victoria)

We still have a long way to go on our renewables quest: - a lot of off-shore wind will be needed; a lot of batteries; and, perhaps, a bit of nuclear?

But not hydrogen, except in exceptional circumstances (see the main article).