Julian Assange is in the news again.

I have commented on his theories and his worries before.

I know no more than you do about his worries; except to say that in his shoes I would be worried too.

But I take issue with his unqualified crusade to reveal the World’s secrets. I disagree that secrets are always a bad thing.

I have worked in both government and corporate business and have agreed with decisions to keep some things secret; or at least to restrict access to some facts to certain people.

On this website I have argued that in life we need to weigh things up for ourselves, rather than applying a universal code or appealing slavishly to authority. This is a world in which there are lines in the sand; balances of probability; best outcomes; and changes of mind.

When it comes to secrecy the shadows can be long; secrets can lead to blackmail and corruption.

But relationships, organisations and civil society all need some secrets. Just as too much secrecy is problematic; so too is having no secrets at all.

Privacy

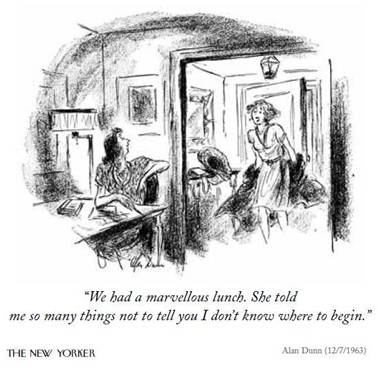

For good reasons, ‘the law of the land’ enforces some kinds of secrecy. Most personal information is protected by privacy laws and regulations. This information is nobody’s business but our own and should be honoured and kept confidential by the limited group with whom we elect to share it. That's a matter of trust; and almost defines friendship.

In our personal relations excessive honesty can be unnecessarily hurtful; it can even be used to be deliberately cruel to others. I’m sure we can all think of an example.

Malicious defamation is a crime even when true. With the advent of social media cyber-bullying is on the increase.

Legally Imposed Secrecy

In law, jurors are denied certain information during trials; witnesses under threat have their location and sometimes their identity concealed. In business, those who bid for tenders are denied competitors information; enterprises must not collude on prices or markets; journalists try not to reveal their sources; and so on. There are many such examples.

In government and business this might involve, as yet unprotected, intellectual property – an invention or new business idea. Or it may be some information not yet public that would be of use to a trader on the stock market or a land speculator.

Even in Julian’s world it appears some secrets are justified. He seems reluctant to fully reveal what went on with those women in Sweden.

But he would, I believe, argue that the covering-up of a mistake in government or business is a clear example of conspiracy.

Mistakes

Perhaps the most important justification for a cover-up is to diminish the impact of a mistake; because without mistakes no progress can be made.

I should make it clear that I’m not talking about corruption, lying or other falsification.

But mistakes are routinely covered by resolving them in such a way that only those who need to know, know a change has been made due to a mistake: ‘Don’t worry about it we’ll do this instead…’

They are then misrepresented to the world as a change of plan: ‘We decided to do this instead…’

If an enterprise is innovative, requires special skill or covers new ground, mistakes can be relatively frequent. But no progress will be made if the team becomes excessively risk adverse.

To some extent the need for managers to resolve genuine and understandable mistakes by team members, as opposed to incompetence, is a function of the job.

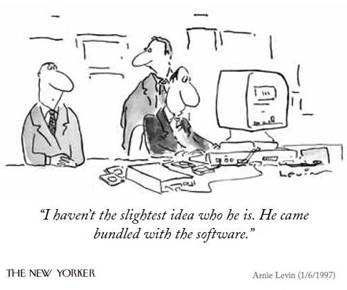

I spent a decade managing people writing computer code. We called undetected mistakes in their code ‘computer bugs’ implying that they were somehow generated by the computer rather than the author. Bugs are much less common than everyday mistakes. These are usually obvious because the code fails to work at all. Yet 'bugs' are so inevitable that all coding enterprises use an elaborate process of de-bugging; culminating in several rounds of user acceptance testing; even then some escape.

There would be no innovation and very poor outcomes if code writers were hassled every time they made a mistake.

But incompetent code writers, who make repeated or silly mistakes, soon run out of credit.

There is a difference and the same rule applies in any enterprise.

A furniture maker who hacks up a valuable piece of timber without measuring or by using the wrong tool is incompetent. One who slips by a sixteenth of a millimetre while carving an elaborate inlay is pushing the boundary of the craft.

A manager leading an effective team needs to protect the skilled but not the irredeemably incompetent. This requires that the manager knows enough about the individual tasks involved to tell the difference.

Surgeons famously bury their mistakes. Yet it is said that every great surgeon has made more than one.

It would be very unfortunate for the many more patients saved than killed, if surgeons were tried for manslaughter every time a patient died. Yet some are clearly incompetent and need to be removed from the system (by someone who understands surgery) before they kill any more.

This is the reason that the claim that a successful manager can do any managerial job is nonsense.

When I worked in the steel industry I was aware of a number of mistakes that cost millions and would surely have displeased the shareholders had they been revealed at the time.

When these were understandable (to superintendents who fully understood the process) the matter went no further. But stupid mistakes were seldom forgiven, particularly if someone got hurt or killed.

In a perfect world everyone would be properly informed and fully understand the basis for the decision. But often specialist knowledge is required to make this judgement. Unfortunately in the world of corporate politics there is often someone ready to make the most of a perceived slip-up.

Maybe it would be of interest to a journalist looking for a scoop?

Conspiracy

Covering for mistakes requires a little conspiracy of the kind Assange decries.

In my experience little conspiracies of silence to protect a team are very commonplace; often contributing to the loyalty that binds effective teams together. This might be as simple as covering for an assistant when they fail to reorder toner, causing a report to be delayed.

Some mistakes are just too big to be kept secret and there is always a risk of secrecy within a team escalating to an unacceptable level. Managers need to use their judgement as to who needs to be informed up the chain of command; and where the line in the sand needs to be drawn. Again in my experience good managers usually do; unless trust has been damaged somewhere up that chain.

Government Secrets

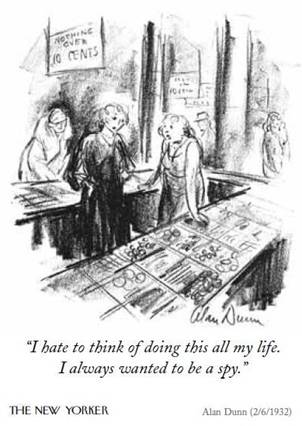

In wartime and sometimes in diplomacy it is very ill advised to give an enemy or opponent prior warning of an action. Often actual deceit is employed to mislead opponents. So governments may employ agents to discover the actual facts; and distribute misinformation; and so on. I've read spy novels.

This world of secrecy has a high profile and may or may not be justified depending on the circumstances. As the US says, lives maybe endangered and diplomacy sabotaged by WikiLeaks.

But another area in which WikiLeaks seems to be active involves revealing the more mundane confidential processes of government. This too could be damaging to the proper functioning of everyday government.

Functional Secrecy

There is a tradition in the Westminster system that advice given to the Ministers is confidential; at least for a period. Ministers are not bound to accept this advice and different Ministers may receive contradictory advice before a Cabinet decision is made.

Decision outcomes soon become public but long experience has taught that it is not always wise to reveal too soon any contradictory recommendations that are rejected in reaching the final outcome.

These are generally made public only after the passage of time; if ever.

Advice is often processed through several steps internally within a Minister’s Department so that the final official advice may differ from early working documents. This may be because the early draft is based on fewer facts or contains errors.

Where these notes are preliminary in nature they may be discussed by email and thus preserved but many are properly considered ephemeral and should be consigned to the ‘round filing cabinet’.

Back in the days of pen and paper my daughter Emily came to work with me one school holidays and when asked what dad did she reported he sat in his office and wrote a page; made a phone call then screwed up what he had written and threw it in the bin. Then he wrote some more and got it typed; after that he threw it away again. That’s his job writing things then throwing them away.

Thankfully I couldn't email my stupid mistakes or random thoughts to anyone back then – it was all pen and paper.