| emergency /uh'merrjuhnsee, ee-/. noun, plural emergencies. 1. an unforeseen occurrence; a sudden and urgent occasion for action.

|

Recent calls for action on climate change have taken to declaring that we are facing a 'Climate Emergency'.

This concerns me on a couple of levels.

The first seems obvious. There's nothing unforseen or sudden about our present predicament.

My second concern is that 'emergency' implies something short lived. It gives the impression that by 'fire fighting against carbon dioxide' or revolutionary action against governments, or commuters, activists can resolve the climate crisis and go back to 'normal' - whatever that is. Would it not be better to press for considered, incremental changes that might avoid the catastrophic collapse of civilisation and our collective 'human project' or at least give it a few more years sometime in the future?

Back in 1990, concluding my paper: Issues Arising from the Greenhouse Hypothesis I wrote:

| We need to focus on the possible.

An appropriate response is to ensure that resource and transport efficiency is optimised and energy waste is reduced. Another is to explore less polluting energy sources. This needs to be explored more critically. Each so-called green power option should be carefully analysed for whole of life energy and greenhouse gas production, against the benchmark of present technology, before going beyond the demonstration or experimental stage. Much more important are the cultural and technological changes needed to minimise World overpopulation. We desperately need to remove the socio-economic drivers to larger families, young motherhood and excessive personal consumption (from resource inefficiencies to long journeys to work). Climate change may be inevitable. We should be working to climate “harden” the production of food, ensure that public infrastructure (roads, bridges, dams, hospitals, utilities and so) on are designed to accommodate change and that the places people live are not excessively vulnerable to drought, flood or storm. [I didn't mention fire] Only by solving these problems will we have any hope of finding solutions to the other pressures human expansion is imposing on the planet. It is time to start looking for creative answers for NSW and Australia now.

|

Since my retirement Wendy and I have done quite a bit of travel, often these days to less 'touristy' places, although that's just a matter of degree. After all we're tourists and we were there. On occasion we've revisited old haunts after a decade or so absence.

Everywhere we go there is one thing in common with our home in Australia: there are a lot more people than there were a decade or so back. Everywhere we go there is evidence of resource depletion, particularly water resources, and environmental degradation. Everywhere we go new dwellings have spread like a cancer across once green fields.and forests. Concrete forests now stand where humble dwellings or open fields once were.

It's no good blaming our parents, the underlying causes of the many environmental challenges we face go back the start of the 19th century and the Industrial Revolution when no longer were the great masses of humanity the children of farm labourers, serfs, slaves or servants serving a small cultured elite.

With industry came systematic applied science, engineering, and improved medical understanding. Now workers needed new skills and had to be educated. With education came many benefits, including independent volition, and improved living conditions. Death rates declined; fertility improved. By the end of the 19th century world population had more than doubled its pre-industrial record, reaching 1.6 billion. But then it really took off.

By the mid 20th century many informed commentators were getting alarmed and calling for population restraint.

In 1968 the world human population had topped 3.5 billion, over a billion since the end of World War 2.

That year Professor Paul Ehrlich, of Stanford University in the US, published The Population Bomb correctly warning that: 'hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.' Critics claimed that he was alarmist, yet very soon 260 of every thousand babies born in Zambia were dying due to malnutrition before their first birthday. In Pakistan the number was 140 per thousand (source: The Limits to Growth).

In the same year concerned scientists in Europe formed The Club of Rome. Three years later the Club published 'The Limits to Growth', the results of a state-of-the-art, yet primitive, multi-factorial computer model that projected the impacts on food consumption/production; pollution and the cost of reduction; energy resources; and non-renewable industrial minerals, of unrestrained exponential population growth. The model forecast multiple disastrous consequences early in the 21st century. The authors feared no less than anarchy, driven by food and resource riots, and the total collapse of civilisation. The final sentence reads: 'The crux of the matter is not only whether the human species will survive, but even more whether the human species can survive without falling into a state of worthless existence.'

|

My copy of The Limits to Growth

Only a few paid any heed. Several of these were later described as the 'Asian Tigers'.

|

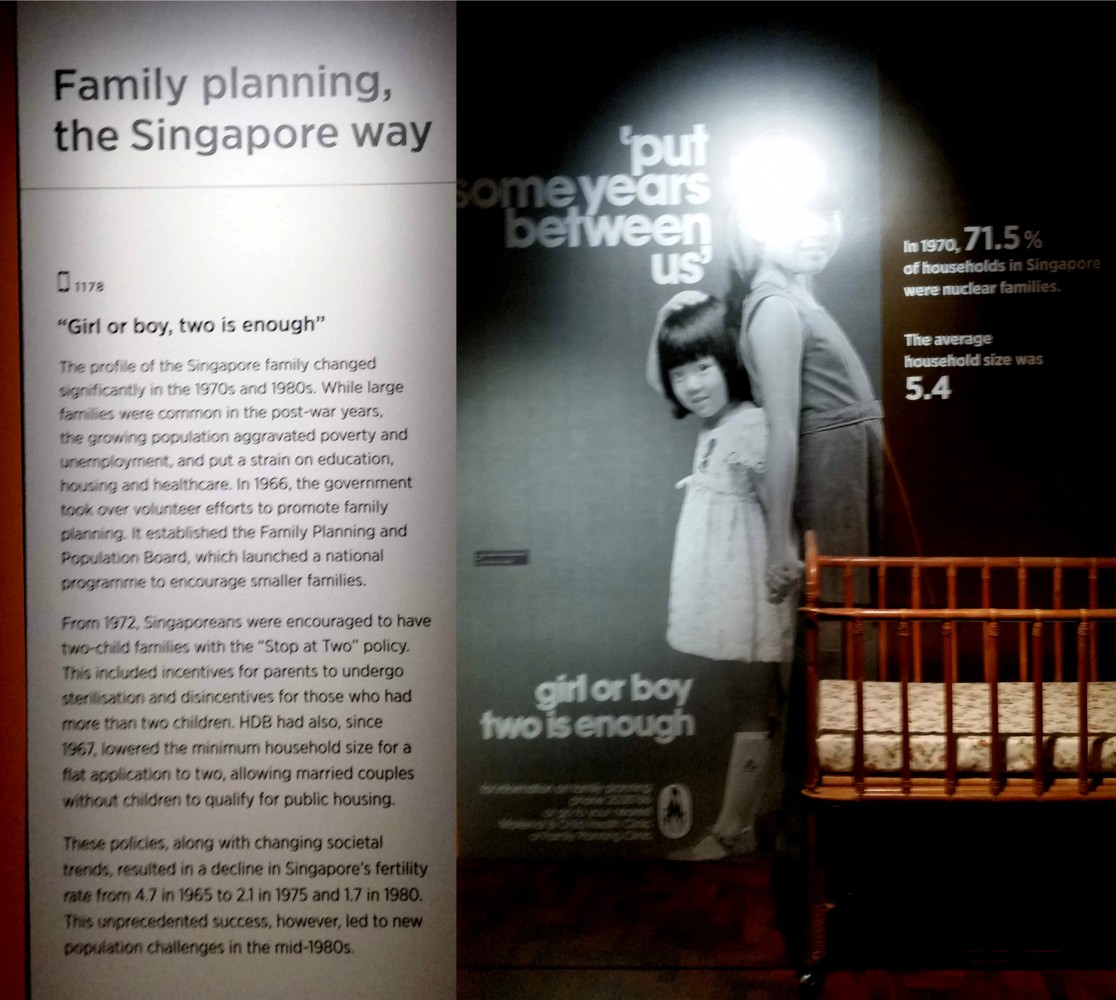

Singapore's Stop at Two policy

From 1972 Singaporeans were encouraged to have two child families

- incentives included payment for sterilisation and public housing for married couples without children

- disincentives included precluding couples with more than two children from applying for public benefits

The result was a decline in fertility from 4.7 in 1960 to 1.7 in 1980

Although the campaign stressed the need for girls, as in China, cultural factors resulted in a preponderance of boys

- an ongoing social and economic problem

Nevertheless, Singapore has gone from a struggling third-world country to become the fourth richest country in the world (1)

On the other hand, since independence in 1947 India's population has grown sixfold

- India will soon overtake China as the world's most populous country - visit and compare

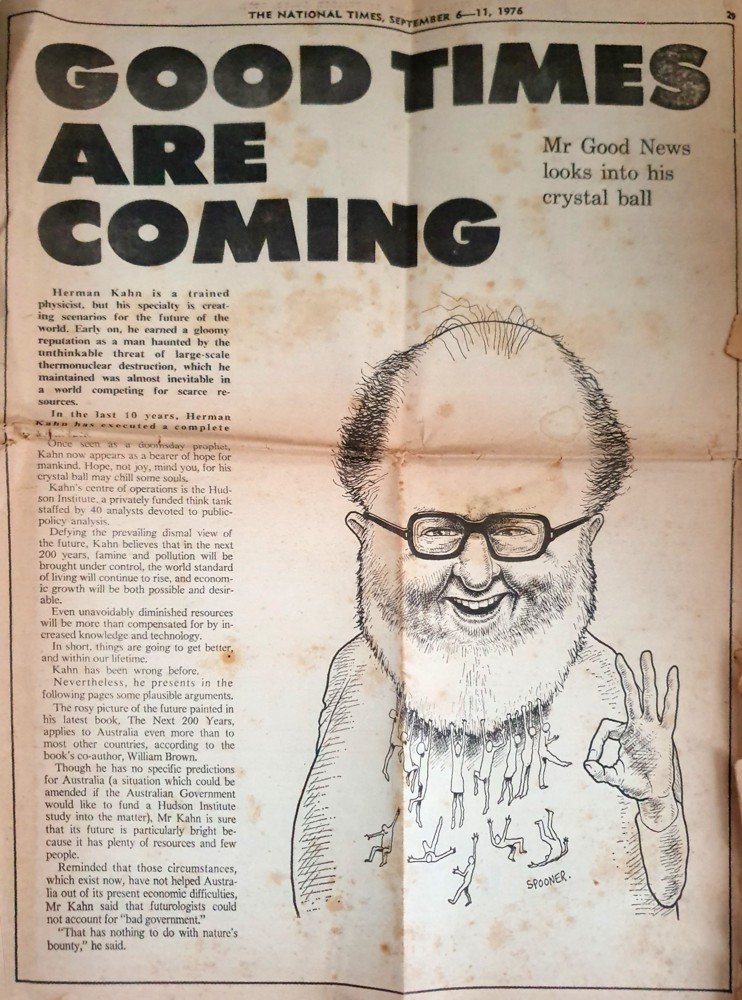

Critics of The Club of Rome, like Herman Kahn, of the Hudson Institute, cried: 'garbage in gospel out', a popular objection to computer modelling at the time, and lo, the Club's projections were soon proven to be overly pessimistic. In the 1970's science came to the aid of mankind. New crops were developed and there was a 'green revolution'; new processes and products improved efficiency and new mining technologies, like remote sensing from aircraft and satellites, together with new extractive methods, like deep-sea oilwells and 'fracking', redefined resource availability. In first world countries rivers and air was cleaned up and pollution ceased to be our number one concern.

|

The Hudson Institute's Herman Kahn's riposte - one of many

The Hudson Institute was later employed by the NSW Government to help plan the State's future

- no mention of global warning

Everyone breathed a sigh of relief - we didn't have to do anything. The religious among us were right: God, or the Gods, had it all in hand - it was all part of 'The Plan'. It was business as usual.

Yet today, the Club of Rome's foremost prediction: that unless we did something, by 2020 world population would reach eight billion has proven alarmingly prescient. And Paul Ehrlich's predictions are also vindicated.

In 2013 a Global Hunger Summit in London(2) was told that: 'Malnutrition is the underlying cause of death for at least 3.1 million children [per year], accounting for 45% of all deaths among children under the age of five and stunting growth among a further 165 million [children].'

Although they factored in 'pollution' as a general concern, the research team behind The Limits to Growth said, or knew, nothing about the specific threat of carbon dioxide. Was this an oversight?

With our new skills scientists now have ice-cores, containing entrapped air bubbles, that go back half a million years. These show a close correlation between global temperature and the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The highest level ever was around 300 thousand years ago, when it was much warmer and carbon dioxide reached 300 parts per million.

Because of man's multifarious activities, including agriculture, the atmosphere broke that half million year record in the 1950's and we have been in uncharted territory ever since. While correlation does not necessarily denote causation, and it's still not as warm as it was back then, I find it rather alarming. Read my paper: Climate Change - a Myth?

It seems highly probable that climate change is at least in part due to the current mouse-plague that we call humanity: clearing forests; digging up the ground; building things; making stuff soon to go to garbage tips; consuming resources without concern for the future and, of course, burning things.

How long can this go on? I hope there will be a deus ex machina, that some, as yet unknown, aspect of quantum science, genetic engineering and/or nuclear energy will save us. Failing that, I hope that current civilisation will outlast my grandchildren and perhaps theirs? One glimmer of hope is the declining fertility in first-world countries as more women have careers beyond motherhood and living standards improve. Yet as I pointed out in 1990 this would consume far more energy than the third world has to hand. Is it now a case of too little too late?

I won't be around to know.

As the The Club of Rome pointed out, and should be obvious to 'Blind Freddy', the indefinite exponential growth, that our economies are addicted to, is unsustainable. 'Soon or later,' as Alice remarked about drinking from a bottle marked 'poison': 'it's bound to disagree with you'.