Progress

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;

A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together; a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away;

A time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace. [Ecclesiastes 3 1-8]

All progress is technological. [Richard McKie]

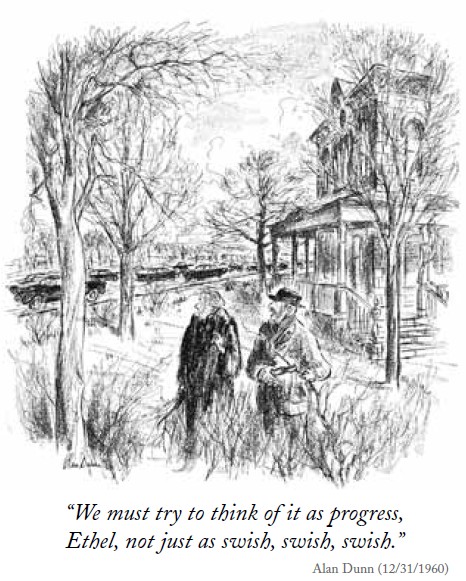

Today many of us take it for granted that progress is a fundamental characteristic of the world. Things change. Most people regard beneficial progress to be the fundamental role of government. Democracy is about government by the people for the people or in other words to make things better for people. Improvement requires change and together that's progress.

In my brief lifetime, since the middle of the 20th century, there has been massive change. But changes during my grandparents' lives from the first half of that century seemed even more dramatic because that's when the modern world of cars and planes and telephones and disease control and radio and electricity and clean water in the home first arrived for most people.

Critics of change were generally those who's old privileges or beliefs or comforts were being challenged. But even the most strident critics of change took it for granted that progress was a legitimate goal of Government. They simply disputed the definition of an improvement.

So it may come as a surprise to realise that for centuries, each spanned by four or five generations, people thought the world was more or less static. This is clearly the assumption made by the Preacher in Ecclesiastes (above). Under this view intervening wars; changes in leadership; acts of god; and accidents of fate; are seen to take place against a constant background of the seasons. Everything old is new again: change is temporary. And a person is destined to do one of the jobs that someone like them in the previous generation did. The skills and tools needed to do a job don't change. Knowledge and skill is constant and handed down one generation to the next.

To some degree this kind of thinking persists. At school it was an accepted lesson of history that cities or empires are like any other organism they grow from some seed of advantage struggle for survival into youthful vigour mature into adulthood until time, ennui, hubris and internal corruption lead to weakness and collapse. So we learnt of the Minoans; the Greeks; the Phoenicians; the Inca and Aztec; the Egyptians; the Romans; the Byzantines; the Ottomans; and as time passed the Spanish; French; Russian; British empires all collapsed. The list might also have included the various dynasties in China and the Khmer empire in Cambodia had we been interested in Asia back then.

The traditional view might have been that at each collapse the clock is more or less set back to the earlier state of general chaotic disorganisation and individual survival until a new organising principle arose and a new civilisation developed, like a phoenix rising from the ashes.

But very recently, perhaps from the 16th century, Europeans noticed that this was not the case. At last civilisation had surpassed the achievements of the ancient Greeks Romans and Egyptians. Not only that but the advances had become exponential. This was no longer a fixed cycle of developing to a point of aging and death to be reborn and repeat the cycle. Certainly individual politicians; political movements; leaders; alliances; and associations; still flourished then failed. But human capabilities and with them, overall wellbeing, continued to expand notwithstanding.

As I asserted above, all change is technological. If we consider the great changes in human capability through history social change has followed the mastering of ceramic firing; writing; metal smelting; and new insights in mathematics; mechanics and architecture. Thus the Romans advanced from the Greeks. It's when technology becomes static that human society begins again the cycle described by the Preacher of the Old Testament. But at a new level of capability.

The renaissance famously restored a level of technology that had been partially forgotten since ancient Rome and Greece. But to suggest that it was just a return to that ancient learning and technology is wrong. In the Muslim world significant advances had been made in mathematics; astronomy; navigation and medicine during a time when Europe returned to the Preacher's times for planting and plucking; peace and war; gathering and casting asunder. So it was the Muslim advances and their conquest of the Byzantine Empire that re-awoke Europe and ultimately called into question the religious assumptions that had stifled technological progress. New ways of thinking, unconstrained by religion, were unleashed.

By the early 18th century European technology led the world facilitating superior ships, navigation and weapons. New understandings about Nature allowed Europeans to conquer most of the world. A century later railways and the telegraph and new business and medical practices consolidated these gains. Soon electricity would be exploited as a means of energy transmission to substitute for human and animal muscle power, for lighting and to enable electronics. By the middle of the twentieth century nuclear power would destroy two cities, disembowel several islands and provide clean electricity to much of Europe. Large warships would become independent of regular refuelling, or the need to return to the surface, and confirm a new age of superpowers. Soon mankind would leave the planet for the first time.

Reviewing the past historians realised that the earlier civilisations too had risen and fallen against a steady increase in human capability from the stone age to smelting found metals like gold to reducing metallic ores like copper and tin to alloying these metals then reducing iron ore with parallel developments in ceramics and glass and transportation and machinery and supporting this had been writing; and teaching; and apprenticeship.

If we wanted a metaphor or simile we might imagine a set of technological stairs, thought time, upon which children play a fantasy game with LEGO plastic figures. On each step any change in wellbeing is entirely due to the plastic figures' institutions and organisation like their legal system and who's got the upper hand over whom. Technology and their knowledge of how the world actually works (science) is static.

New scientific knowledge and the changes in technology this allows creates a step up. On the bottom step bottom there are no metals -just wood and stone and string and resin. On the step up the seasons and seeds are understood and there are farmers; above that there are large stone buildings; then swords and chariots; and so on; until we reach sailing ships and cannon; then steam trains; and then aircraft and radios.

On each step the plastic people go about their business in cycles just as the Preacher of the Old Testament says. They play politics and power games; they mate and fight; and succour and care for others; and do all the things that humans do. The chattering classes chatter or pursue fashion; things are made and are thrown away; the rich and powerful exploit the poor and weak; power-struggles between the elites in society carry the average plastic person along in the flood. All the plastic figures have a role in the game until they crumble to dust. Then they are replaced by others recast from that plastic dust; and the cycle repeats.

At the bottom our metaphorical steps are wide, extending for thousands of years and each technological jump-up is small. But as time goes on, the time between major technological advances grows shorter and the jumps-up become higher. So that instead of steps we now have a steep ramp, where there is no stable platform for the old cycles to take place. None of the old plastic certainties are certain any more and each successive generation of plastic people is faced with an entirely technological new world.

We might expect much the same uncertainty in our flesh and blood world where progress and technology are now almost indistinguishable.

If technological progress stopped tomorrow could we expect that we would return to a society in which each generation would more closely mirror their parents lives, save for the usual externally imposed cyclical cycles of drought and flood or the occasional catastrophic incidence of tsunami or meteor impact? Of course dictators and demagogues would come and go as always; the chattering classes would still chatter; the rich and powerful would still exploit the poor and weak and power-struggles among the elites in society would still continue but there would be no advance on mobile phones or present generation aircraft or driverless cars.

The answer is no. There would be significant falling back from our ability to do and make these things.

Our present economy relies on continuing technological change and would quickly collapse without it. For example agriculture and medicine are only sustained through continuous innovation and unless we find new ways of storing or collecting energy we may be doomed. The resulting economic collapses would devastate world populations and many abilities we now have would be lost as a result of billions of premature deaths.

In advanced countries like Australia only about 5% of post school qualifications relate in some way to science or engineering - and that includes the engineering trades. In the case of devastating social collapse resulting in mass starvation the people who could fix anything at all complex or even explain the theory behind how say the electricity; water; gas; telephone; or cellular radio (mobile phone) systems worked could well be reduced to unworkably small numbers. Can you repair your mobile phone or even your modern car? Do you know enough about how they work to make one, even if you had the right tools?

Eventually humanity would recover and go on as before but on a lower technological step. Many of us could build a basic car or steam engine, for example.

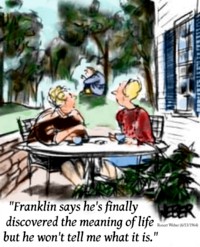

So the question implicit in the quotation from Ecclesiastics remains: If everything is just repetition, what is life all about anyway? Is one step actually any better than another? Was my great-great-grandmother in Victorian times any worse off than my daughter, in terms of the things that count in life?

The explanation that we exist simply to amuse the gods, playing with us like the children on the stairs, or just one God, is not satisfactory to me.

As to the second question. I'm inclined to think that the ability to fly to anywhere on the planet that takes her fancy is a big advance on having her horizons limited to the same town that constrained my ancestors, condemned to relatively unchanging amenities in housing, domestic appliances and health. Similarly, my daughter can enjoy a wider range of cuisines, unconstrained by the season of the year, clothing is no longer for survival but a relatively trivial fashion interest and everyone is freer to pursue a wide range of other interests no longer limited to our particular trade or employment.

Even for those who can be easily amused, for example by spending many hours watching teams of other people endlessly running, kicking or hitting balls around a field, the ability of television to get in close to professionals in action is a big leap from having to go down to the village oval to watch an occasional match between amateurs.

But for me: regular international travel; or the ability to learn about the human genome or cosmic background radiation or other advances while sitting at my desk; or to see my grandchildren in real time in Germany on my phone are not abilities I would ever want to go back from.