This essay is most of all about understanding; what we can know and what we think we do know. It is an outline originally written for my children and I have tried to avoid jargon or to assume the reader's in-depth familiarity with any of the subjects I touch on. I began it in 1997 when my youngest was still a small child and parts are still written in language I used with her then. I hope this makes it clear and easy to understand for my children and anyone else.

What is this identity you call 'Me'? What is culture and what is knowledge? What is truth? What is goodness? What is success in life? Why are we here? Are there any rules? How do our culture, upbringing and nature work to make us what we are? Can we talk about the 'meaning of life' at all, or simply about 'the presence of life'?

Others have told us most of what we think we know. How can we trust them? Why do we believe what other people around us believe? We tend to believe trusted messengers and to be suspicious of untrusted ones irrespective of the message. How do messengers gain our trust?

Ideas and speculations are fundamental to what it is to be human, unique among the animals of this planet and probably in this universe. I hope you will enjoy mine and find something useful in them.

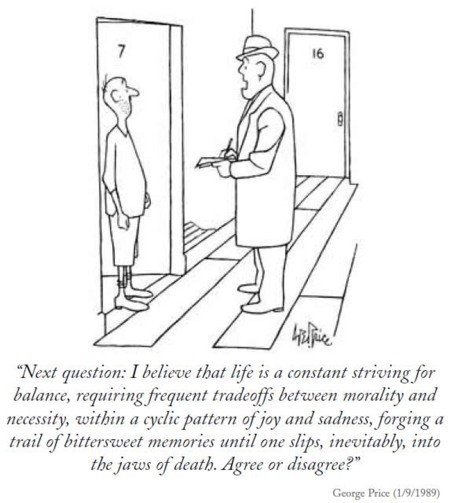

The title: The title is well tried but it amuses me as both a wink to an essay of the same name by John Anderson (of Sydney Push fame)[1] and to Monty Python. Since 1997 I've added and amended it a number of times and as I am now reaching maturity and may not have a lot more to add I've added a subtitle 'things I have learnt' ..

Introduction

I said in mine heart concerning the estate of the sons of men, that God might manifest them, and that they might see that they themselves are beasts.

For that which befalleth the sons of men befalleth beasts; even one thing befalleth them: as the one dieth, so dieth the other; yea, they have all one breath; so that a man hath no pre-eminence above a beast: for all is vanity.

All go unto one place; all are of the dust, and all turn to dust again.

Who knoweth the spirit of man that goeth upward, and the spirit of the beast that goeth downward to the earth?

Wherefore I perceive that there is nothing better, than that a man should rejoice in his own works; for that is his portion: for who shall bring him to see what shall be after him? [2].

This essay has a number of themes. Notwithstanding this insightful quotation from Ecclesiastes (in the Christian Bible and Jewish Tanakh), central to all is my belief that the way to truth and understanding; knowledge and worth; purpose and happiness; is not through an appeal to the authority of wise men of the past (or their writings) but through a sceptical analysis of contemporary ideas and values, some of which do indeed owe their origin to the ancients.

This analysis is central to what I have called The Great Human Project, the understanding and mastering our immediate universe. This is a collective endeavour that gives a purpose to the otherwise fleeting existence of humanity. It goes beyond purely individual goals; like a sporting record; becoming a millionaire or the acquisition of power or fame.

The Great Human Project distinguishes humans from all other animals on this planet through the expansion of real knowledge and collective capability. But to accomplish this we must learn to sort the good ideas from the bad.

The principal test of an idea is its utility in correctly predicting otherwise unknowable outcomes and that it survive our concerted attempts to prove it wrong. Because we cannot personally test every contemporary idea this involves a reliance on trust in others. But I suggest the ways we might approach this problem.

Out of this systematic scepticism we have come to accept those ideas that have been arrived at by 'scientific method' and to reject ideas that cannot sustain 'scientific analysis'. These 'truths' are highly dependent on place and time. As our knowledge changes so does the 'received truth'.

Using these methods it is now believed the universe came into existence in a primal event about 13.8 billion years ago. The earth is a little more than a third of this age; bacteria infected it quite soon; developing multi-cellular plants and animals a little over a billion years ago. Humans, along with other modern mammalian species[3] have been here for about one seventy thousandth of this time. The universe will continue for many tens of billions of years after our sun and earth are long gone, together with all earthly life forms.

Each higher animal (including each of us) is a constantly evolving colony of cells and symbiotic organisms (from mitochondria to gut and skin bacteria). These cells, that come and go during our lives, form the super-organism that is us and service its functions just as they do in any similar super-organism from the 'higher animals' to plants.

Variation is introduced by sexual reproduction, structural variation and imperfect replication. Continuous environmental change favours one design over another. The functional designs for each animal and plant are tested against success in the prevailing environment and the more successful multiply while the less so are reduced.

Humans fill an environmental niche, unique to this time and place, that substitutes social cooperation and the processing of ideas for advanced physical attributes. This has enabled us to move from a highly threatened species, on the edge of extinction, less than one hundred thousand years ago, to world over-population today.

In this sense 'the meaning of life' has nothing to do with us. We are simply an accidental and probably redundant part in the continuum of a series of physical, biochemical and evolutionary processes under the influence of the formative circumstances and present characteristics of this planet. But in this essay I want to go beyond this 'reason for life' to the human experience; our perception of a life of meaning and purpose; and our belief in our ability to be an active agent in the flow of our lives.

Most if not all animals are 'aware'; they seek food and turn from danger. They 'enjoy' being comfortable. Even plants turn to the sun and attach themselves to things and some catch insects. But only a few animals are aware of being aware. As far as we know only humans are aware of ourselves, and others, being aware of being aware. It is this 'meta-awareness', the awareness of our own awareness, that leads us to the illusion that we have a 'mind' that exists separately to our 'body'.

Our intellectual and social capability is a two edged sword; it has given us unprecedented control over our environment but also a grandiose view of our own importance both as a species and as individuals ': for all is vanity'.

Source: all cartoons are from The Complete Cartoons of the New Yorker 1925-2004, unless otherwise indicated.

I will argue that it is our ideas that distinguish us; that are fundamentally important to being human and to being the person that we are. Just as we are capable of formulating ideas that have utility in improving our survival and wellbeing and that have enabled us to make initial forays to other planets and to alter the fundamentals of terrestrial life itself; so we are capable of holding ideas that are wrong and harmful, indeed the evidence is that we are very attracted to wrong ideas.

In this essay I will try to suggest the ways in which we can escape harmful ideas and value, enrich and enjoy our lives, notwithstanding their fleeting and ephemeral nature.

Although the 'truth' of any proposition lies in its utility this does not mean that it is true in every context. I will argue that all human knowledge is contingent and uncertain. Newton's laws are useful and adequate to for predicting the path of a space shuttle or the next lunar eclipse; Maxwell's equations for predicting the behaviour of light or radio waves; and Rutherford's atomic model is a fair approximation of an atom for use by chemists and biologists; but none of these stands up to detailed relativistic or quantum analysis. I will explore some of these ideas in more detail.

Being human involves a lot more that beliefs about ultimate purpose, creation or 'truth'. We share with other species needs and desires for food shelter and reproduction and like other mammals and communal species we depend on our parents when young and value the support of others.

Other animals gambol and play but we alone have evolved ideas, cultural diversity and civilisation. We alone have organised entertainment; music, painting and literature; we alone value ideas.

I will spend a good deal of time considering what it is to be human, with reference to important thinkers that might profitably be read in the original.

We are a combination of our genes our experiences and our ideas. Like all other organisms we inherit our genes from our parents and our experiences from our environment. As humans we also inherit our ideas from our parents, our peers and the community at large.

Together with the context of our birth and accidents that later befall us, these collectively determine if we will become a scientist, athlete, priest, criminal, king, pauper, diva or drug addict. Yet as I will argue each has his or her place. Each irrevocably changes the future and all that will be; some to a much greater degree than others.

But for each of us, ours is the only universe there is; we each live in our own unique field of perceptions. When we end, all this ends 'all are of the dust, and all turn to dust again'. There is no more.

Each of us has a choice of 'project' for our lives. For some it may be selfish; an Olympic medal or wealth or fame; to be admired for our beauty; to own something; to collect stamps; to spot trains; to play with a ball in public; or a thousand other individual goals.

For others it may be to mobilise society towards the great collective goals; exploration; knowledge; technology; capability. These things cannot be accomplished alone.

A theologian or mystic might 'sit alone beside the fire', like Descartes, and arrive at almost any profound position. They can be independent of society. But even the most reclusive rationalist must 'stand on the shoulders of giants'. I too have stood on many shoulders in writing this essay.

The Great Human Project can only be achieved corporately, with each player taking their part: on the stage; behind the scenes or creating the theatre.

So what can we aspire to in this brief candle? I will let the reader decide. In the telling of these ideas I will touch on the place and importance of our culture, art and religion, personal relationships and love, children, economics and market forces and the impact of new scientific ideas and discoveries on us all.

This essay is written in sections that are loosely linked but stand alone, so you can skip around without 'losing the plot'.