Technology

The things I found interesting were the technical and intellectual capabilities implicit in the engineering architecture; manufactured products, like jewellery and weapons; and scientific knowledge implicit in the practices and beliefs at different periods over 10,000 years of human civilisation.

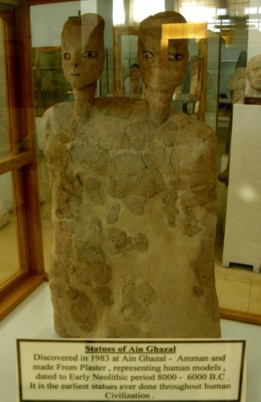

8,000+ year old statues in Amman Museum

Even the early Stone Age cultures of Syria and Egypt are impressive. Early human and animal figures in plaster stone and ceramics have been found.

Very sophisticated stone arrow heads and fish hooks as well as sophisticated pottery show not only a high level of manufacturing capability but an excellent means of acquiring; preserving; refining and improving; accurately recording; and disseminating knowledge. Perhaps they used now lost, drawings or early writing to complement the traditional teaching of elders and apprenticeship as can be found in aboriginal Australia. But aboriginal Australians either migrated to Australia before the bow and arrow and pottery were invented or lost this knowledge by some misadventure.

Stone arrow heads in the British Museum

The next technological leap is huge and must have involved written communications (as is confirmed by archaeological evidence), craft specialisation, numeracy and commerce.

I started my career in the iron and steel industry and know something of metal smelting. Metal smelting is not something you ‘wake up one morning and start doing’. It requires knowledge of high temperature kilns and furnaces, a sophisticated knowledge of high temperature ceramics (advanced pottery), in addition to a geologist’s knowledge of ores and fluxes.

One metal, gold, occurs naturally and can be melted directly at relatively low temperatures so it is possible that metal smelting began with gold but it is also possible that it began when potters were attempting to add high temperature glazes and discovered the first metals by accident.

Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin and in most cases these ores are found widely separated, so the true Bronze Age was preceded in the Iberian peninsular and probably in the Middle East by copper, tin and gold technology. It is difficult to stress the sophistication and depth of knowledge required to smelt then alloy metals. From chipping a flint stone tool to metals smelting is a technological leap of a similar magnitude, as ‘The Golden Hind’, Drake’s Elizabethan ship, to The Space Shuttle.

Anyone capable of harnessing these metals and the sophisticated communications and world view they imply had a new resource of immense advantage, spreading into every corner of commerce and society from warfare to agriculture; and so we see the great Bronze Age Egyptian, Mycenaean and Babylonian cultures begin.

The most dramatic and lasting evidence of these new capabilities are the Pyramids of Giza.

Sphinx with Great Pyramid in the background – Giza October 2010

These are at once evidence of the vast organisational capabilities and rapidly expanding knowledge of the early Bronze Age and a reminder of the limits to their world view.

The Bronze Age Egyptians placed their full confidence in a panoply of gods that explained away every event success, or disaster, providence cast their way. They committed vast resources and considerable parts of their lives to preparing for a highly improbable life hereafter.

As Byron put it:

What are the hopes of man? Old Egypt's King

Cheops erected the first pyramid

And largest, thinking it was just the thing

To keep his memory whole, and mummy hid;

But somebody or other rummaging,

Burglariously broke his coffin's lid:

Let not a monument give you or me hopes,

Since not a pinch of dust remains of Cheops[5].

Although quite a number of their carefully prepared mummies can now be seen partially unwrapped in climatically controlled rooms in Cairo, along with almost everything from Tutankhamun’s tomb and lesser contents from others, not a pinch of dust remains of Cheops.

These mummies are remarkable for being amongst the oldest preserved human remains on earth. It was interesting to speculate while wandering these rooms on the ridiculousness of their conception that, if correct, would have their souls returning to find them in a glass box in Cairo. I have had similar thoughts about the medieval knights transposed to the Cloisters in New York to await the second coming they believed imminent. Among the organs torn to pieces during mummification, to extract through the nose, was the brain, as the Egyptian soul resided in the heart; an idea that comes down through the Bible to popular culture; some superstitious believing this today, even after heart transplants have become commonplace.

Tutankhamun (1333-1324 BCE) was believed to be the son of Akhenaten (of monotheistic sun worship) referred to above. Still a boy he changed his name and reverted to polytheism under the influence of the priests.

Among the contents of Tutankhamun’s tomb on display are four Egyptian chariots. They were drawn by two small horses, light weight, equipped with quivers for arrows and carried a driver and an archer. The harnesses are quite advanced but the carriage lacks any suspension except that the passengers stand on a woven floor, probably leather, no longer in the carriages.

Chariot in the Egyptian Museum – Web photograph - no photography permitted.

The chariot was a technological advance used predominantly by the Hittites to allow the use of horses in battle. The Hittites developed a new chariot design that held three warriors instead of two. With it, together with bronze weapons, the Hittites gained control over Mesopotamia and eventually the whole of Syria, dominating trade routes, particularly trade in metals. In 1299 BCE Ramesses II attacked the Hittite city of Kadesh in what is thought to have been the largest chariot battle ever fought, involving some five thousand chariots. The city did not fall but Ramesses claimed the victory as the faster Egyptian chariots prevailed. The battle resulted in a treaty with the Hittites, the Kadesh peace agreement, which we saw some years ago at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. This is believed to be the earliest example of any written international agreement of any kind. An enlarged copy of the agreement hangs in the UN building in New York.

This was a time of rapid technological advance for example in casting (mass producing) bonze weapon components, forging iron swords improved archery with composite re-curve bows and new forms of armour. The best bows required the strength of Heroes to draw them and the arrows had great range and penetrating power. Pikes and spears became formidable weapons.

Chariots continued to be important over the next thousand years but were eventually superseded by more manoeuvrable mounted cavalry as larger horses were bred and first girth straps then saddles were improved; culminating in the introduction of stirrups, from Asia during the Middle Ages.

By the time of Alexander the Great (330 BCE) chariots were as dubious a weapon as horse mounted cavalry is today. When attacked by chariots his cavalry simply parted then perused and destroyed them from the rear. After that they became a ceremonial and sporting vehicle used for parades, and games and circuses for public amusement during Greek and Roman times, where chariot races were enormously popular, being sponsored by wealthy patrons for political reasons and the object of gambling.

Re-enactment of a Roman chariot race – in the ancient Forum at Jerash - Jordan

There are references to the Kadesh battle in the hieroglyphics at the temples in Luxor, Karnak, and Abu Simbel. At Karnak our guide failed to point these records out, being rather more interested in the various gods depicted there. But we did see where Merenptah commemorated his victories over the ‘Sea Peoples’ on the walls of the Cachette Court.

During the reign of Merneptah (about 1224 BCE) and again during the reign of Ramesses III (about 1186 BCE) Egypt came under attack by ‘Sea Peoples’ a term coined by the Egyptians and recorded in the accounts of military successes inscriptions and carvings at Karnak and Luxor.

‘The foreign countries...made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were on the move, scattered in war… the unruly Sherden whom no one had ever known how to combat, they came boldly sailing in their warships from the midst of the sea, none being able to withstand them… Their league was Peleset, Tjeker, Shekelesh, Denyen and Weshesh’.

It is probable that the threat of the sea peoples armed with new iron weapons gave Ramesses II (1279 -1213 BC) incentive for strengthening Egyptian fortifications and for his grandiose buildings we still see today.

In the main temple at Karnak the sun god Amun-Re is hallowed. There is a large and famous statue of Ramesses II, amongst many other smaller figures at the site, and it is the second most publicised and visited place in Egypt after the Pyramids.

The Great Temple to Amun-Re at Karnak begun by Ramesses II

The development of iron technology was another giant leap forward. While bronze can be smelted in a relatively low temperature furnace similar to the one a blacksmith might use today, as we saw in use in Damascus, the temperature required to smelt iron can only be achieved in a much more sophisticated blast furnace, blown with preheated air. The feed for the furnace originally combined iron ore, charcoal and limestone (flux). The consumption of timber required to make charcoal was vast and occasioned the felling of entire forests.

Basic iron objects are brittle as cast and could only be toughened up by repeated reworking in a forge, beating-out and folding or drawing to oxidise the high carbon content. To make a superior sword or armour required many hours of work and great skill; but once steel quality was achieved made a weapon that, in the hands of a powerful soldier or Hero, could cut through bronze like butter.

As a result old civilisations, steeped in traditional ways and defended by conventional bronze weapons, fell to the barbarians: up-start with little respect for traditional arts and letters. And it was some time before the new regimes thus empowered began to develop their own cultural values, arts and religion. This period is known as the dark ages. Historians point out that the world was changing in other ways around 1200 BCE. This was a period of significant tectonic plate movement in the Mediterranean with two major, climate changing volcanic eruptions and several very large earthquakes. These may have weakened the established civilisations and left them more vulnerable to attack.