Knowing

We know nothing at all. All our knowledge is but the knowledge of schoolchildren. The real nature of things we shall never know.[15]

Thinking humans have realised for thousands of years that we don't see the world as it actually is. There must be things we are not seeing or that we are not seeing correctly.

For example nearly 2,400 years ago Plato proposed the theory of 'forms' or pure ideas that lie behind the world of senses; that we see only shadows of. This idea has been influential ever since. It was imported to Christianity (via St Augustine) and to Islam and is still believed by many today.[16] That 'reality' is different to perception is a common theme in Science Fiction.

If our perceptions are wrong what can we know 'for sure'?

You can say that you know that two plus two equals four because that is what 'four' means (one plus one plus one plus one and this is the same as two groups of two). In the same way you can say that you know that 'the sun is somewhere in the sky during the day' because that is what the 'day' means (the time between sunrise and sunset). There is no need to look; if the sun isn't there it isn't the day. These statements must be true because of the meaning of the words used.

In philosophy they are said to be true 'a priori' (from a cause: the day is the time between sunrise and sunset; to an effect: the sun will be somewhere in the sky during the day).

If we say we 'know' that there are trees in the back garden it is probably because we have seen something in the back garden that we recognise as the kind of thing generally called a tree. But if we are not looking at them when we say it, we may need to be pretty sure that trees are not in the habit of walking off when we are not looking. You couldn't say, 'I know that there is a bird in the back garden' unless you could see or hear it (or you had locked it up or stopped it leaving some other way).

In philosophy this kind of knowledge is called 'a posteriori' (from effect: the image in your eye and brain; to the cause: the 'thing' that looks and behaves like a tree). You can only know these things by experiment (looking in the garden). Because a priori statements must be true and a posteriori statements need to be tested; a posteriori statements are more interesting and more useful.

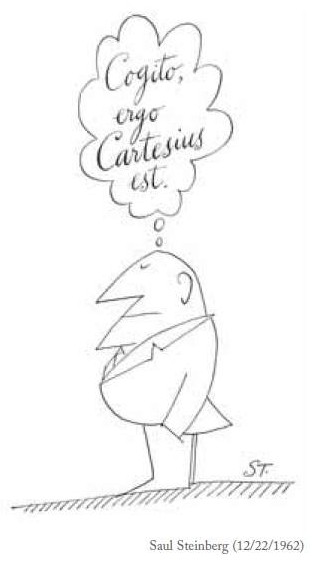

350 years ago René Descartes wanted to know what we can know for certain. He wrote the words Cogito, ergo sum, in Latin this means, 'I think, therefore I am'. This was apparently an 'a posteriori' or experimental truth that had the status of an 'a priori' truth, because it can't be wrong. Philosophers argue about this but individually we each can say, 'something exists that I call myself', even if we can't prove anybody else exists. Maybe I have made up everything in the universe, including you, in my mind; whatever that is. 'I' may be an illusion but something exists.

I think therefore Descartes is

Since Descartes wrote 'The Cogito' people have tried to find other things we can know for certain but it turns out that we can only know most things on the balance of probability. They might be 'very likely true' and sometimes they are clearly wrong.

The word 'know' has a number of different meanings. If I say in the street, 'I know that person', I generally mean that, 'I recognise that person'. If I say, 'I know the way to the kitchen', I mean that, 'I recognise (or I can work out) where I am now and I remember (or I can work out) how to get to the kitchen from here'. In a similar way I might say, 'I know how to make a cake' or 'I know how to use a computer', meaning: 'I remember and understand how to do it'. I can do it again even if things are a bit different next time.

None of these is the same thing as 'knowing' that there were dinosaurs. We only know that there were dinosaurs because other people that we believe have told us so. Maybe we should say we 'believe' that there were dinosaurs. Almost everything we know is this kind of rather uncertain knowledge (about animals and stars and planets and atoms and the environment and other countries and how a car works; just to name a few).

The past, in particular, falls into this area of uncertain knowledge. First, our own observation of events as they happen is frequently limited or incomplete; what did happen? Next, different people at the same event see it differently. Then, some people at an event deliberately lie about it or exaggerate or make it more interesting when they retell it ('put a spin on it' as journalists say). After all that, our memories are notoriously faulty and can easily be manipulated so that we can become convinced we experienced things that we did not. This is the basis of so-called recovered memories, re-birthing experiences and the like, that are planted in the victims heads by the unscrupulous or naïve.

I have deliberately put these types of knowing in this order because they are less and less certain. The first kind really doesn't tell you anything new; just that you understand the idea behind the words. The second kind depends on your understanding of the words and believing that the things you see or hear or feel or smell are real; that you are not being tricked or dreaming or mad or on drugs. The third kind depends on these things and also that you remember and understand things. And the last kind relies on all these things and on other people telling you the truth or on your being able to tell when they are wrong or lying.

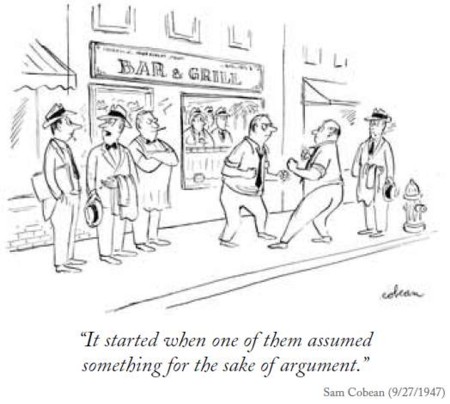

So to know things this last way you have to work out if other people are telling you the truth. This is very difficult. They may be deliberately lying to you or other people may have lied to them without them realising. Nobody may be lying but they might be wrong for other reasons. People are often wrong about things. It might be that the words we use and the concepts they stand for are wrong. Often we are just ignorant; no one knows.

One way we do this is to decide if we can trust them. Most people believe a University professor, a teacher, a priest or journalist more than say a sales person. So if a sales person tells us something that is true and a professor tells us that it is not, unless we have some other way of checking, we will tend to believe the professor.

The order in which we trust them might in turn depend on how we were taught by someone else. Many people believe that a priest is the most plausible of all. Most believe an encyclopaedia more than a TV show and we believe some newspapers more than others.

In recent times some radio commentators have been passing themselves off as journalists, when in fact they were sales persons. As a result people, who would otherwise have been justifiably suspicious of what they were saying, may have believed them.

I know that if I had been brought up in the thirteenth century, and had been one of the fortunate people to get a good education, I would accept as an absolute and obvious truth that: 'God made the world in seven days and placed it at the centre of the universe'.

As you go through life you will find yourself constantly amazed by the messengers that other people seem to find plausible. But why do we have different views?

A lot of our knowledge, belief and experience are tied up in the words we use and how we have learned to use them. This is why I talked about words first. You had to learn what a cat is before you could use the word cat properly and so did any person you want to talk to about cats. The same goes for atoms, dinosaurs, love, God or government.

We can only have some kinds of complex thoughts because we have the words to express them and we only have those words because someone before us had similar thoughts.

Knowing changes as words change and little by little we can change our words or make new ones and know more. If all words and ideas are available to us we can use the useful ones and not use (but don't completely forget) the ones that don't seem to have much use.

Scientists test ideas to see if they are useful. One way is to see if ideas or propositions can be used to predict something (if they can't they don't have much scientific use) then to see if the thing they predict actually happens. This is known as scientific method or empiricism.

Many of its ideas go back 250 years to a Scottish philosopher, David Hume. 250 years seems a long time but it is only about three modern lifetimes. British, German and American philosophers like Locke, Kant, Wittgenstein, Russell, Dewey and Popper, have refined them since.

Empiricism says that any statement that cannot be tested is meaningless. It argues that all we can know has to go back to the things we can observe (things we see, feel, hear or smell; maybe with the aid of an instrument like a microscope) and the relationships between them.

Earlier I said that the postmodernists are unhappy about Logical Positivism. Like empiricism Logical Positivism argues that scientific theories are hypotheses that must be testable by observation. It adds that the test should be experiments designed to falsify the hypothesis. If a hypothesis survives all efforts to falsify it, it may be true.

If this is so, no scientific theory can ever be fully tested because we can never test a hypothesis enough. So science, nor anyone, can never prove an idea beyond all doubt. Everything is in some degree of doubt but we can know some things more than others.

The hypothesis of Logical Positivism is of course itself subject to the same kind of doubt and stands ready to be changed or improved if we find a better method. In the world of science and technology these methods have applied selective pressure to our ideas for two centuries.

Because of the idea of empiricism we are now able to think in ways that no one has before, in the hundred thousand years that mankind has been trying to find out why we are here. This is the reason we can now do things that we could never do before; like going to the moon, sending e-mail or changing the genetic code. But one of the outcomes of empiricism is that we have confirmed that the world is a lot stranger than we used to think it was.

At the subatomic and universal levels scientists now talk about quantum weirdness and more than three dimensions. There are other complex things going on, including the conservation of quantum information that are difficult to understand. We can't see atoms, or the particles that we deduce that they must be built from, and we do not feel time or gravity in a way that makes logical sense when we consider all the evidence. The way we feel and see our world is very human; and not anything like it must be. I will discuss these things in more detail later.

Empiricism is a method of finding out which ideas are useful in a practical way and which may be more useful as insights into how people think and feel and need to believe in our culture. It tells us that astronomy is useful to science and understanding but astrology is only useful to sell media and hope and to make people feel better.

Thomas Kuhn has argued that scientists do not make fundamental discoveries by systematic application of Logical Positivism. He suggests that fundamental discoveries are those that break with 'accepted paradigms' in the history of science.

A scientific paradigm can be likened to a jigsaw puzzle; all the pieces must fit together to form a coherent picture. Finding a verified fact, that does not fit, requires a paradigm change: we must undo the whole area that does not fit and rethink it from the beginning. So it is important that facts are properly verified: they do not stand alone but as a part of our currently validated 'world view'.

Thus discovering that there really are angels or fairies or that Astrology is valid would require some pretty drastic revisions to the presently verified scientific paradigm.

For example: not long ago computer programs were a lot simpler than they are today. Computer programs were 'procedural'. This means they might tell the computer to do something like 'ask the user for a number; do something to it (like work out the cube root or add it to other numbers) and then print the answer on the screen or save it for later'.

But this was not much good for games. When you design a game you might want a little character to run about on the screen and react to other things (like monsters or rewards) as if it was an individual. This requires a new kind of computer program that creates classes of objects of a particular type (characters, monsters, rewards) that can move about on the screen independently.

These need to react differently in every game you play and seem to have 'a mind of their own'. To do this they need to have computer code that can change some of their characteristics (like their position or colour or size) without changing their basic design (like their shape or how they react to being shot at). This code needs to be owned by the character and to be activated only when that character is created or reacts to something.

This would be very hard to do if every character had to be fully rewritten every time it moved or changed colour. This led computer programmers to invent Object Oriented Programming.

Object Oriented Programming allows a programmer to design a class of objects (like monsters) and use this to create lots of monster instances when the game is run. These inherit the general properties of the monster object from their class but they add their own variations (like colour or position on the screen).

It turns out that not only is this idea good for writing computer games but it also led to programs that use a computer 'mouse' to drag things around on the screen and helped Microsoft to invent 'Windows'. As a result almost all new computer programs are now written this way when just a few years ago they were almost all procedural.

This is just one example of a complete change in direction of ideas and our way of thinking.

At different times in Science and in life we have dramatically changed our basic ideas. People once thought the earth and then the sun were at the centre of the universe. They thought there were only four elements. Until recently they thought that atoms were solid; like little grains of sand. At first people did not accept the theories of evolution or of relativity.

These people were not stupid. If you had lived then, and been an educated person, you would have believed the same things.

It is certain that we will find new ways of thinking in the future. We call fundamental shifts in the way we think about things 'paradigm' shifts.

The interesting thing about these shifts is that we are often quite happy with our old ideas; until a new way of thinking quite suddenly proves to be more useful. You may have seen a picture of a woman that can be old or young depending how you look at it. Sometimes ideas are like this.

Another view is that it is the very failure of old ideas to pass the test of verifiability that result in an accumulation of pressure to look at the data from a different perspective. Empiricism provides the day-to-day test by which data and ideas can be filtered.

The vast majority of scientific discovery and invention requires systematic analysis and not fundamental changes in direction.