Society

'Never speak disrespectfully of Society, Algernon. Only people who can't get into it do that.' [43]

For most of recorded history human society has been organised by class based on wealth and position. Christian worship makes numerous references to knowing one's place, honouring one's betters and giving charity to those beneath us.

With the change from the feudal system; the social inequities of that social model, and growing rural unemployment, developed to the point that many people were seen as useless (or worse).

In 1764 Cesare Beccaria promoted the view that the function of society was to take the 'essential man' and turn him into a citizen by the application of laws arrived at by consensus. This idea was taken up across Europe and refined by thinkers like Thomas Malthus[44] and Jeremy Bentham. These argued that the State is responsible for society and for how people behave; for moulding how people behave so that all may live better.

Early economists like Ricardo and Adam Smith, who argued that labour rather than land was the source of wealth, reinforced these ideas. From the late eighteenth and through nineteenth centuries these ideas led directly to social reform experiments like the establishment of New South Wales and later to calls for universal education and democratic social reforms.

By the twentieth century a number of competing social models had developed. The model on which the United States, Canada and Australia were founded, and which most Western Countries came to apply, drew on thinkers like Jeremy Bentham and John Stewart Mill. This model emphasises individual striving for wealth as a means of individual and social improvement.

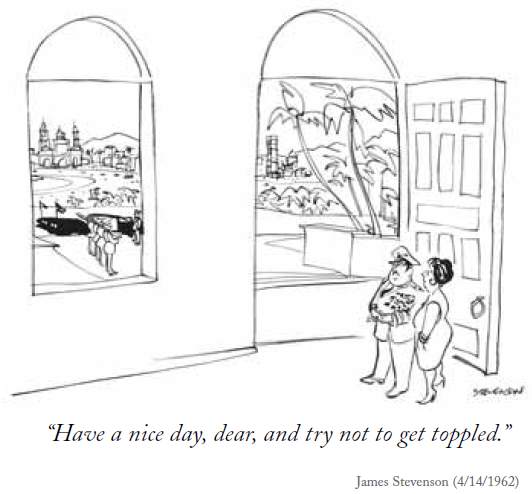

'Eastern Block' countries applied a model based on the thinking of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Amongst the ideas promoted was 'from each according to his ability to each according to his needs'. But to achieve this in practice they proposed an economy in which the State owned most of the businesses producing goods (like things we use or eat) and services (like banking, communications and entertainment). Marx believed that this model was superior and would succeed by historical inevitability but others believed that it could only succeed 'out of the barrel of a gun'.

It seems that both were wrong. For a while countries like Australia, Britain, Italy and France tried a mixture of private and State owned businesses but by the end of the century most countries in the world had privatised most State owned businesses.

Different societies make the claim that they are or could be 'the best of all possible worlds'. The French thinker Voltaire satirised this idea in Candide (a short book that you must read). Elsewhere Voltaire supported Beccaria's view that providing work would make men honest citizens.

Sometimes people argue that there should be no government (anarchy) or that 'society' is a fiction. But we know that when government fails the responsibility for enforcement of social order falls to the most powerful and this is often-tyrannical. To restore social order after a breakdown the first thing that must be done (after securing and clean water, food and shelter) is to re-establish the rule of law.

Experience shows that the primitive model (with a chief or King) is unable to compete, economically or in producing successful ideas, with one in which rules are set by some means of social consensus (agreement by most people).

Advanced societies presently achieve consensus (commonly held beliefs and values) on social rules and structures through the interaction of lots of competing forces. These include: representative governments (democracy as we practice it); direct participation by lobby groups; the 'spin' applied by the media, advice from and management by the public service; legal decisions based on precedent, the common law and judicial bias; international agreements and the (hopefully enlightened) self interest of big corporations. Improved communications are changing how societies develop consensus.

Apart from providing basic law and order, all presently successful societies give government the ultimate management of land use and the responsibility to provide some common services. Streets and pavements; their location; the things that run under them like water, drains, telephones, electricity and gas and over them like busses, cabs cars and trucks are all regulated and sometimes provided by government. The exchanges, dams and catchments, water treatment plants, gas & coal reserves and businesses they lead to cannot exist without government imposed rules of ownership and commerce.

Advanced societies have found that it makes economic and social sense to ensure that people do not live in abject poverty or suffer excessive social disadvantage or ill health. It adds to social success to maximise consumption and thus production, to avoid social unrest and to satisfy our desire to do 'what is right'. Successful societies value education and make sure that the State provides quality education to all capable of benefiting from it.

Whether government runs businesses or not, for societies to be successful, governments must impose rules for citizenship and structures that limit, encourage or direct business activities. It doesn't matter which society you live in, it will have rules and structures that have evolved like other ideas and designs (this is discussed more later on). Citizens are expected to conform to these or to suffer the consequences. All societies seek to civilise children, to set limits to individuality; to create citizens.

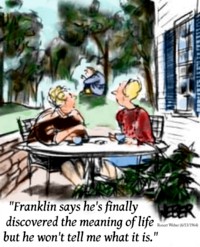

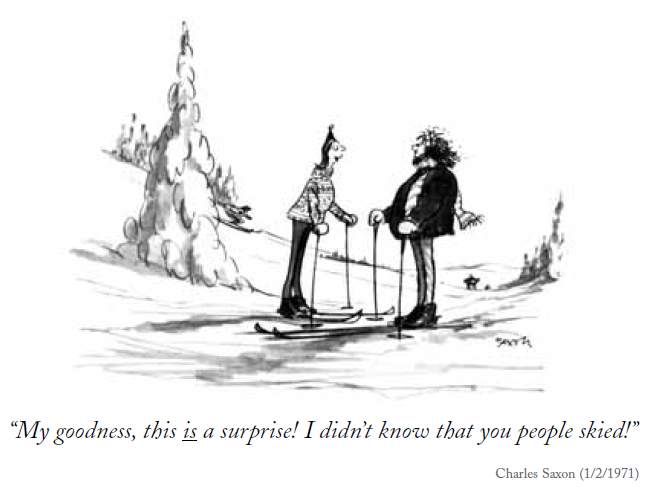

Because societies promote stereotypes, for many people, the meaning of life is defined by their position as a member of society: 'I am a doctor, a solicitor, an accountant, an architect, a bricklayer, the Prime Minister', and so on. They might even believe that God sets the social rules. Such people have a certain nationality, class, religion, place in a family, job, activity or social position that is 'them' and are very uncomfortable when others want to change definitions.

For existentialist thinkers like Kierkegaard, Kafka and Jean-Paul Sartre this kind of existence, in which people are reduced from a person into a thing, is a contemptible denial of being (or bad faith). But for most, success in life (in contrast to meaning in life) is provided by our place in society. Success is measured against society's values: becoming a leader, making money, being a member of the elite, being a good parent, being a good worker, giving time to charity and so on.

Those who are able might struggle for social improvement or to extend human knowledge.

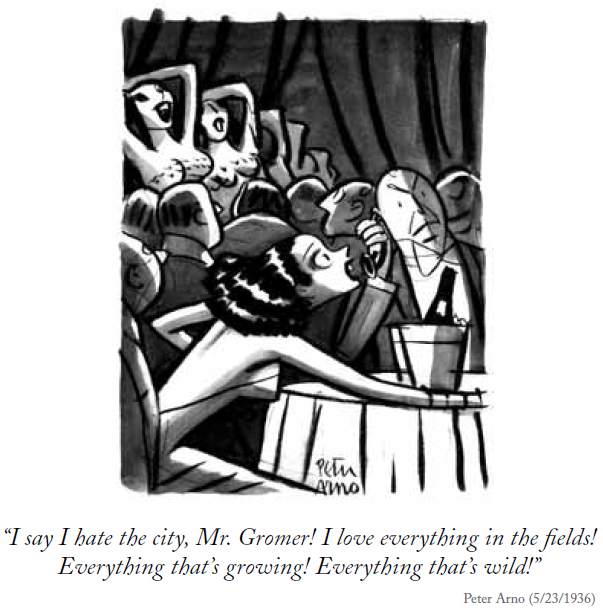

Our culture also has a long tradition of cynicism about the ultimate value of social position and particularly unearned wealth or privilege. Our religion holds that spiritual values are more important than physical or worldly things (like wealth or position). Christ disapproved of materialism.

Shakespeare puts the words:

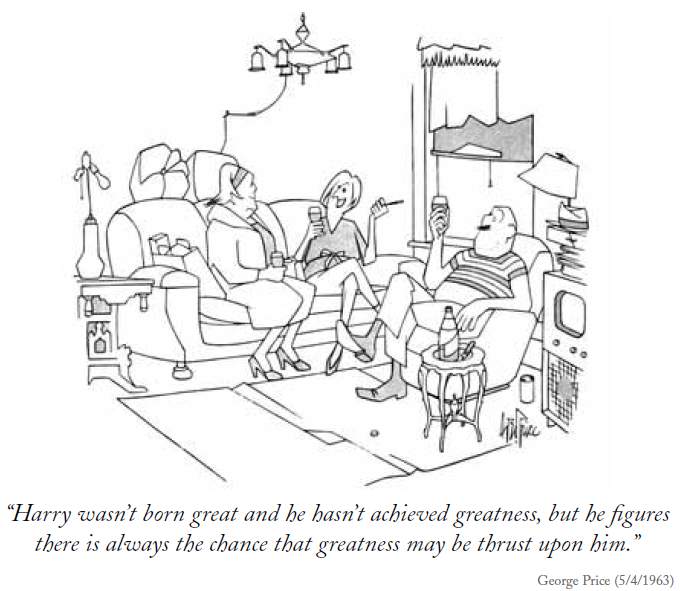

Be not afraid of greatness:' 'twas well writ:

Some are born great.

Some achieve greatness.

And some have greatness thrust upon them.[45]

(via a letter) into the mouth of one of his most archly drawn objects of derision; the stuck-up, social-climbing Malvolio. It is amusing that these words are sometimes quoted to provide some meaningful insight, when they are intended to make the speaker seem a fool.

Elsewhere Shakespeare is at pains to suggest that greatness (leadership, destiny, royalty) is a mantle taken up by an otherwise ordinary person. 'And what have Kings that Privates have not too, / save ceremony ...'

Today we might replace Malvolio's 'greatness' with 'wealth and privilege'. We can respect those who achieve (earn) wealth or privilege but have difficulty respecting those who are born to wealth or privilege; like Pooh-Bah:

'I can trace my family back to a protoplasmal primordial atomic globule. Consequently my family pride is something inconceivable.

I can't help it. I was born sneering.' [46]

or simply get them by some other chance; like lottery winners.

Yet, as I will point out later, all of us are to some extent inheritors of wealth; both material and intellectual (ideas, knowledge and the means to benefit from them).

In statistics there is a 'law' called the Pareto principle. This was first developed from the observation that in every society he looked at Pareto found that a small number of people have most of the wealth (typically around 20% have 80% of the wealth). This applies to many situations in society and in Nature (eg 20% of the farms produce 80% of the exports). It has nothing to do with the worthiness of the successful but rather with their exploiting advantage the instant they get ahead of the pack. Wipe out one wealthy class and a new one will rise in its place.

Succeeding in a society can be the source of pleasure and a sense of value. But a society is not an end in itself. Society only makes sense if it gives something to individuals that they could not achieve alone. This could be fast cars, a boat, nice clothes, watching meaningless activity, hanging out, Prozac, Viagra, uppers, downers, pot, heroin or coke, or just a big TV set; many think so.

But you might come to agree that it has more to do with access to ideas (art and science) acquiring skills and knowledge and maybe, even, the achievement of wisdom. You don't have to become a thing or deny your potential as a person.

Rather than fitting into a stereotype (school, university, job, marriage, children, retirement, death) life can be seen as a journey through a series of adventures. The heroes and anti-heroes of literature are often depicted this way. Jobs, locations, relationships can all change. In this view of the world it is a bit harder to work out who is successful and who is not but life is a lot more interesting. Maybe the increasing divorce rate is not a measure of social ills but of richer lives.

Changes in technology are leading to social change. It is likely to result in more people working globally (eg via the Internet or for transnational businesses) but living locally and this is likely to result in big changes in how we each see society in future.