- Introduction

The accompanying story is ‘warts and all’. It is the actual memoirs (hand written and transcribed here; but with my headings added) of Corporal Ross Smith, a young Australian man, 18 years of age, from humble circumstances [read more...] who was drawn by World events into the Second World War. He tells it as he saw it. The action takes place near Rabaul in New Britain.

Corporal Ross Smith

At no point does he tell us about his concern for freedom; for the women of his family or for the Australian way of life. These had little or no influence on his decision to join up.

Of course he had deep love and regard for his mother but in his circumstances he had no reason to love ‘existential freedom’ or his Australian way of life.

For some reason the Japanese had decided to attack Australia. They were clearly the aggressors and when someone attacks you, you fight back. They were small, Asian, determined and implacable. They had a strange religion that regarded their Emperor as a God and admired courage, ‘family honour’ and death before surrender.

He came to fear and hate the Japanese and to see their defeat as a ‘job of work’ to be done; and in that there is implicit patriotism, nationalism and not a little xenophobia; all certainly reciprocated by the Japanese soldier.

The story tells us of his desire for something different and exciting in his life; the prospect of adventure; a need to prove himself; to be equal in guts and strength to other men; to carry more than his fair share of the burden; to ‘be there when the whips are cracking!’.

We can speculate that has always been a primary motivation of young soldiers; in the armies of Ozymandias, Alexander the Great, Caesar, Napoleon, Wellington or Haig.

There is initiative in our young man’s preparedness to take risks and break the rules. But at the same time here is a picture of a young man with an underlying respect for authority and the social structure. The officers have a battle plan; and they are to be obeyed without question. For him and his mates the only important thing is the immediate action; the immediate surroundings and the next few hours or days.

Once in action it is kill or be killed. It’s like rabbit hunting at home where he became a 'crack' shot. But now against rabbits that shoot-back and kill your mates; that lay ambushes and booby traps; and torture prisoners. At one point, recalling Tol Plantation, his anger overwhelms us. He still regrets the one that got away.

Maybe the lot of our fighting men and women today is a different. Maybe they each understand the strategic significance of each action and the importance of each objective. Maybe they can make moral judgments ‘on the fly’ and weigh the benefits and necessity of completing an action; or abandoning it because the moral cost is too high or the strategic gain too low.

Maybe they see the enemy for who they are; understand their motivations; understand their fears; and weigh the cost of death, on both sides, against the benefits of future freedoms and new affiliations. We might like to think so. But then, that’s the image we are given when the remember those that ‘gave their lives for freedom’ in many past wars.

We are used to fictionalised war. Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Full Metal Jacket’, like many other movies, attempts to give us a sense of the immediacy, chaos and surreal disconnectedness of battle. Full Metal Jacket is the story of a single action during the Battle of Hue in Vietnam but was not shot there. We recently visited the actual site and were struck by the waste of lives on both sides to reach the present, rather lovely, outcome. But I was also struck by the realisation that this present is entirely contingent on that history; just as it was.

And so it was in New Guinea. Each act of bravado; each bout of malaria; each bullet’s flight; was essential to our young man’s survival and to the circumstances of his future. In due course this future led to a chance meeting with Joan at Luna Park in Sydney; to their courtship and marriage; then to the birth and nurture of their children and so on; to grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

But unlike the movies this story is not fiction; except insofar as it is seen from a particular perspective; through the prism of memory. I hope you find it as interesting as I do.

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN

For those of my children and grandchildren who are sufficiently interested to learn about some of my experiences in the Second World War 1939-1945 the following is only a short account of some of the highlights that may interest you. I will endeavour not to bore you with any insignificant details which in my opinion anyway are not worthy of mention.

Because we are all of different generations you may have some difficulty in understanding some of the places and events about which I have written but it will serve to give you a history lesson of a bygone era of which I was a part.

The volunteer

As they say ‘I heard the bugle call’ at age 18 and decided then and there to do my bit.

Being on defence work at the time I was exempt from joining any of the services so I had to ask my employer first. He called the army and asked them did they want me. Not being deaf at the time I heard one say over the phone “is he big enough to carry a machine-gun?” After a short glance at me my employer replied “he’s big enough to carry two machine-guns”. “Ok – send him over.” “Within 24 hours I was in uniform - Private Smith RK regimental number NX176860 (a good soldier never forgets his regimental number).

After two weeks at the showground washing up Dixies (pans) and peeling spuds I was sent by train with other soldiers to an infantry training Battalion at Cowra.

Almost every soldier at some time or another went ‘AWOL’ (absent without official leave). It was not really a serious crime unless of course you did it whilst in the front line then you might face a firing squad, but at home the sentence was pretty light, i.e. a weeks wages deducted from your pay-book and confined to barracks for a week, but anything over two weeks was considered to be serious and for two years you would be charged with desertion and a two year jail term or more.

Being fully aware of what I was doing I went ‘ack-willy’. Let me tell you why. I knew only too well that as soon as I had finished my infantry training at Cowra there would be no home leave; I also knew that where I was going there was a very good chance that I would not be coming back. So I decided to go home and to maybe say my last goodbyes to my family.

I knew the provo's would be checking leave passes at the station so in the dead of night I clambered up off the ground on the wrong side of one of the old steam trains of the time. After gaining access to a carriage I hid myself in the loo and as soon as the old ‘puffing billy’ moved off I came out and made my presence known to the rest of the passengers.

After spending about a week at home I decided to go back but remembering some advice I had gotten from some fool in my platoon and me being a bigger fool for listening to him, I turned myself in to the provos (military police) at Victoria Barracks in Sydney. I was immediately paraded before the commanding officer there, Colonel Ironmarsh. The first thing he said to me was “why did you surrender yourself to me, why didn’t you go back to Cowra yourself and be tried by your own Commanding Officer”? Being a little naïve at the time I simply said that somebody had told me that you were a very fair person to be sentenced by. I detected a little glimmer of a smile to his subordinates and then he said, ‘Well I’m sorry son but it’s not my place to try you. You will have to be held in detention here until such time as your unit can send down an escort and take you back to Cowra to be tried by your own battalion commander’.

After realising what a fool I had been, without any more ado I was then put in a dungeon. I don’t know what else you could call it as my memory goes it was a very damp cell or room without bars, just thick, heavy stone walls only about 7ft by 3ft3” with a small pallet or mattress about 2” thick soaked hard and lumpy by dried urine and stank like the sewer. A very thick, formidable looking steel door secured by a lock as big as your fist with a hole in it just big enough to pass your boots out through it every night. I spent three days at Victoria Barracks before my escort arrived and what a three days it was!

Before we go any further I would like to make it known that I did not like being locked up one little bit. It is a terrible thing to lose your freedom even for a few days but it had its benefits. It was a real education for me. Every day they would ‘release’ us all from our ‘cells’ into a big common ‘pen’. All I did was to sit on the floor and watch. They (the other inmates) would walk backwards and forwards all day like caged lions and sometimes one or more of them would find a small strand of tobacco in one of their boots, hats, shirts, pants and God knows where else. Then they would all ‘pool’ what they had and somebody would come up with a cigarette paper and make what they said was a ‘racehorse’, a very thin cigarette; bum a light off one of the guards and pass it around. But the best was yet to come. I was amazed at the looks of ecstasy and delight on their faces as each one of them took one puff, probably the first one they had had for a very long time. I learned at a very early age what drugs can do to a person.

At the end of about three days my escort arrived with side-arms (bayonets). I knew them both and I went back to Cowra, as predicted to be tried by my own CO, a weeks wages deducted from my pay book and one week confined to barracks.

At the completion of my training there I was sent to Canungra, a jungle training camp in Queensland.

A week after I arrived in Canungra the Japs broke out of their prison camp at Cowra, killing several guards and creating much mayhem before the uprising was put down, after many were killed. It was against their code of honour to be taken prisoner and their built up frustrations finally came to a head at Cowra.

The idea of sending us to Canungra was to train us to fight in the jungle with the objective of sending us to New Guinea.

Going to War

From Canungra they transported us by troop train to Townsville, where we embarked on an old troopship called the ‘Katoomba’. The time it was to sail was a closely guarded secret. All I know is I woke up out of a sound sleep in my hammock ‘spewing’ (buggers of things those bloody hammocks) which continued for 24 hours every day for seven days without let up. When you don’t eat it doesn’t help you to ‘dry-retch’. Your stomach turns over and nothing comes out except maybe a little bile. I don’t think there is any worse malady except maybe malaria which I have had three times.

We eventually arrived there after surviving not being torpedoed by a Jap sub; the bastard had already just sunk a hospital ship, the ‘Centaur’ with the loss of hundreds of lives, only a couple of miles out from Cairns. Upon our arrival they loaded us onto ‘duks’. After sailing through a choppy swell for about a mile the ‘duks’ drove straight up onto the beach where we were then offloaded onto waiting trucks to our encampment.

It was then that I was sent to reinforce the 19th Australian Infantry Battalion already located there at a base area which had already been overrun. I was then allocated to 7 Platoon, A Company and shown to my tent which was occupied by several other men of my section. I had already been given a rifle with a grenade launcher attached. It was not my scene. Since I was 14 I was always an avid rifleman and did not want to be some bloody bombardier. Within minutes of sitting on my stretcher I noticed this little guy with a Bren-gun (a light machine gun fitted with a 30 round magazine and weighing approximately 12 kilos – a very formidable weapon indeed and one of the most popular firearms ever invented.

I soon made everybody present aware of my distaste of the ‘thing’ I had been given and said to the guy with the Bren “I hate this bloody thing; I wish I was on the Bren”. The little guy looked at me in amazement. He then disappeared out of the tent and within minutes reappeared with the Platoon corporal. The ‘Corp’ looked at me somewhat bewildered; “Private Smith I have been given to believe that you want to go on the Bren. Is that correct? OK Private Smith you are now the Bren-gunner”. The little guy breathed a sigh of relief. I was ecstatic. “I’ll be there when the whips are cracking” I said!

Sometimes in a show of bravado to convince anybody in your close proximity that you are not lacking in courage one might be heard to exclaim: “I’ll be there when the whips are cracking!” But say what you will it is only the ‘moment of truth’ that separates the men from the boys.

There was a little river which we crossed over every night to watch movies on the American circuit but all that recreation was soon to come to an end when we were sent on a liberty ship (an all steel welded ship - not riveted as were all other ships at the time) which was to transport us to New Britain.

After an eight day voyage zigzagging all the time in an effort to avoid some lurking submarine we managed to arrive unscathed at a ‘behind the lines’ base called Jacquinot Bay. Apart from being sick again I would like to tell you that we had to both shave and wash in salt water (cold). We also found out that soap does not lather in salt water.

To continue; we then had to scale down a rope-like lattice work slung down over the side of the ship with weapons and haversacks over our shoulders onto amphibious ‘duks’, just like you see in the movies; after that sailing for about a mile and up onto the beach the same as before; then onto trucks again to our camp.

After about a week there they loaded the whole Battalion onto landing barges and sailed up the coast for about 12 hours (sick again) to a place called ‘Catup’ in the wide bay area of New Britain towards Rabaul, a big Japanese base of about 100,000 men that had been captured from a small Australian garrison, namely the 2nd-22 Battalion.

When their Commanding Officer saw them coming, he sent a message to Canberra in Latin {morituri te salutant - my note}, translated; we who are about to die salute you, like the Gladiators of Ancient Rome. But more about that later.

After marching for about a week we set up camp again; that night they sent us down to the beach to unload stores from American barges. It had to be done at night because of the danger of being stopped by Jap zeros (Japanese fighter aircraft).

About 9pm I wasn’t feeling well so the ‘Lieut’ told me to go up to the camp and lay down for a while. On the way I was challenged by a sentry. He said “halt who goes there” twice. As I said, I was sick, I wasn’t feeling too well so I said to myself, “the stupid idiot. Here we are still miles away from the nearest Japs and here he is saying halt who goes there”. He said it again, this time with a little ‘menace’ in his voice. I thought I had better say something so I said “okay mate it’s only me”. He then screamed at me and said “f@#k you Smithy I was just about to pull the trigger when I recognised your voice”. I nearly shit in my pants. Anyway, enough of that.

Enemy contact

The next time we finally got ignition the whole Battalion was standing on the road to Rabaul; on one side of the Henry-Reid River stood Waitavalo Plantation, on the other, Tol Plantation. Without any warning a Jap machine-gun opened up on us. We all hit the ground pretty quick. The bullets were cracking around our heads like thousands of whips. The reason for that is the bullets are travelling so fast that they break the sound barrier, hence the crack. We had just experienced our first ‘baptism of fire’.

I was shit-scared, I am not afraid to tell you. I don’t know about the others, although I didn’t see anybody laughing. Our Platoon made a left diversion to about 200 metres downstream and forded the swiftly flowing river, weapons held high trying our best not to be swept away. Luckily we made it to the other side without incident. We then advanced up a ridge called Cake Hill.

After about two or three hundred meters the first contact was made – by me! I heard this scarping sound at my feet. To my surprise I was standing alongside a Jap pill-box or bunker with a rifle barrel sticking out of a gun turret, with the half obscured head of a Jap behind it. In the blink of an eye he pulled the trigger. I could feel the muzzle blast hit my thigh and the bullet missed me. When he saw me standing there with the Bren he must have panicked and fired too soon. I made no such mistake and gave him a burst of about eight rounds straight into his face and then threw in a grenade for good measure. I heard one of my mates say to me “he just took a shot at you Smithy”. I said “yeah I know”.

Upon returning that afternoon there were three dead Japs laying flat on their backs, just outside the pill box or bunker. For your information a pill box (in the jungle, anyway) is a big hole dug into the ground large enough to house two or three men with a series of logs cut from coconut trees slung across the top and then covered with a huge mound of earth, with three or four gun turrets for observation and firing strategically placed around it, and a crawl trench for entry and exit. These pill boxes as they are termed, as basic as they may be, can withstand the explosive direct hit of a 25 pounder (artillery shell). Anyway so much for the pill box let’s get back to the action.

Now the two other sections of my Platoon had advanced on ahead of us and we heard a hell of a fire fight up ahead. The next thing we saw was two of our mates running back, each with one of his arms shot up and hanging uselessly by his side. We never saw them again but we heard later that they had both lost an arm. Poor buggers, what sort of future would they have? By then it was our turn to take point again, which we did, only to find the Japs had now withdrawn. My Platoon commander, Lieutenant Mick Ferndale, told me to take up a position at the base of a slope and be ready for a counter-attack which could come at any moment. Typical of the tropics, it was very hot, sweaty and uncomfortable. After lying down behind the Bren for about two hours I needed to have a drink badly but to do so meant taking both hands off the Bren in order to reach my water bottle on my hip. But I knew if I did and the Japs attacked at that moment, it would have been too late.

As it turned out my vigilance soon paid off, because without any warning a big crowd of Japs came charging over the Knoll in one of their famous Banzai Charges. I opened up on them with the Bren and with the additional supporting firepower of my mates we made what was left of them withdraw in disorder. I will not sicken you about what happened to the Japs who fell, for any sympathy we had for them was in short supply.

There was no more action that day and we all settled into our perimeter for the night. Down came the rain again and we all had to lie down on the wet ground. Where we lay everything that crept and crawled was there; mozzies, ants, spiders, worms, leeches, snakes and God only knows what else. But the worse thing of all was to hear the rain making these funny pattering noises as it hit the ground and you would swear to God that the Japs were creeping up on you.

Sleep was almost impossible with your imagination running away with you. In the jungle at night you cannot see your hand in front of your face. Every man in our section of nine had to keep watch, if such a thing was possible, in one hour shifts. We only had one wrist watch between us which was not luminous. You had to pick up one of the many thousands of glow worms on the ground attached to a leaf, and believe it or not if you held it very close to the face of the watch you could just barely make out the time.

We had to tie a vine to each man where he slept and then feel your way along it to where your mate was laying, give him a bit of a shake to wake him for his turn to keep watch and risk being shot into the bargain. You must never go to sleep on watch; if you do you are not only putting your own life at risk but all your mates’ as well. Men have faced the firing squad for this offence.

The one that got away

I remember another little incident that I will never forget - but first let me explain; I was never what some people might say, a very sharp eyed individual. Having said that, one day we had momentarily stopped on our patrol when all of a sudden, most of my mates, if not all, saw a Jap running down the track and the two point scouts both opened up on him with their Owen sub-machine guns. Now the Owen, as good as it was, only had an effective range of about 40 to 50 meters. Not so the Bren! The problem was I did not see him and the bastard got away. Now I know what the Bren can do and I know what I can do and let me tell you this. Had I seen him I would have lifted the bastard off the ground with the Bren.

It really bugged me that I had let him get away, even today it still bugs me and sometimes when I am sitting down at Circular Quay and I see an old Jap about the same age as me walk by, I say to myself “for all I know you could be the bastard that got away”.

One more thing worthy of mention: We were out on patrol again - let me first explain - the idea of a patrol is to consolidate your position, kill as many of the enemy that you can and make the whole area secured. To continue, after travelling some distance we heard a machine gun, it sounded like a ‘woodpecker’, the nickname we gave to their heavy machine gun similar to our Vickers but with a slightly slower rate of fire. That seemed to be how it earned its moniker.

The Platoon sergeant said to the Platoon commander “they weren’t firing at us you know Mr Ferndale”. It was the last words he ever uttered. The bloody woodpecker zeroed in on us and let fly with all its fury. We all hit the ground. Col, who had been standing right alongside of me, must have been a bit slower getting down. I heard the bullet hit him. If you were to hang a wet blanket over a clothes line and give it a big whack with a cricket bat you’d hear thwack. I think that is the same noise the bullet made when it slammed into his guts. When you cop it in the guts you know how you are going to die. How could you possibly live with all your intestines mashed to a pulp? How could your food be processed? The poor bugger died soon after.

As for me, I had been lying down flat on my back with the Bren alongside me and praying fervently to God that I would not get hit. I knew the bullets were very close because of the deafening noise they were making around my head. When the firing stopped and we all got back on our feet, the Lieut said to me “Smithy set up the Bren over there and cover our withdrawal”. They all went back and left me on my lonesome. I remember one of my mates saying “good luck Smithy” and I said “thanks Jim”. This time I was not scared, I had just turned 21 and after all I had been through I was now a man and a veteran and by the God Almighty my commanding officer had given me a job to do and I was determined to carry it out to the best of my ability, whatever the consequences.

Within three or four minutes Japs emerged around this bend in the track. I did not fire straight away; I waited until about four or five came into view. And then I let them have it. I saw them all get hit and the rest of them withdrew. I knew they were either going to try and outflank me or silence me with their two inch mortar. Luckily for me Mick reappeared and said “come on Smithy, you can come back now”. Within minutes we had rejoined the rest of the Platoon and then we all withdrew back to the comparative safety of our perimeter some distance behind us.

A perimeter consists of the whole company, about 100 men set up in the shape of a perimeter giving all around defence against attack. About an hour later the Lieut said “come on let’s go back and get them. I said to myself “What! He’s got to be mad. Here we are just escaped being killed and here he is saying, ok let’s go back”!

But you must realise that an officer has got to set a good example to the rest of his men and build up their confidence in the face of adversity and even lead them in if necessary.

In the First World War 1914 – 1918 there were far more junior officers killed than there were men of the lower ranks taking into account the ratio of the ranks that were killed.

At this point I would like to point something out to you and don’t ever forget it. When an officer says to you do such and such a thing, even you though you know that as soon as you do it you are 100% going to get your frigging head shot off, you do it without so much as a second thought. That’s discipline for you. A lot of people today don’t even know the meaning of the word.

Anyway, back we all go; when we reach the spot where we all got shot at the man in front of me went mad (yes – mad). He turned around towards me with his eyeballs staring out of his head saying he could see Japs ‘all around him’. Now let me say certainly I was a little bit ill at ease but I was a long way from going mad. It seems some people ‘snap’ quicker than others. Mick detached one of the men to take him back to our perimeter. We all knew him as ‘Paddy’. I remember seeing him years later at the March on Anzac Day, he seemed quite okay then, but I think somehow he will always be another victim of the war.

The good die young

I forgot to mention earlier about our drinking water. It was never fresh as you know it. It was (brackish) half salt and half fresh, you would bloody near ‘spew’ when you drank it. But of course you had no choice. Also we had to go sometimes a week or more without a wash or even taking off your boots to change your socks. If you took them off they were that covered in mud you would have had trouble putting them back on again. There were no little streams or brooks up in the ridges, there was only drizzly rain, mozzies, sweat, mud, fear, prickly heat, discomfort and Japs.

If there was something we all feared the most it was Jap’s 4.2 mortars. The first warning you had was a little ‘putt’ in your close proximity and then this terrifying rushing of air just prior to the shell exploding with a deafening roar. Even when you were lying down you weren’t safe. We used to call them Daisy Cutters. The bloody thing killed many and wounded more. There was something else probably on a par with the mortar and that of course was the machine gun, especially when it was set up at the end of a long track. They would not shoot the first man to appear, they would wait for the whole Platoon to be lined up behind each other then they would open up on you (enfiladed fire). Nobody but nobody liked long tracks.

Another thing we soon learned to fear was the ‘booby-trap’, usually a cunningly concealed wire about ankle high, strung out across the track hidden by a fern or something so you would not see it attached to the pin of a hand grenade with a four second fuse. We all took turns at doing ‘point’. If any of those nasties didn’t put your lights out they would certainly make you suffer.

After spending some weeks up in the ridges our company was relieved and we returned once again down to the coastal area of Tol Plantation, the scene of a very infamous massacre of Australian soldiers. I will elaborate in much more detail about that later.

During the time we had spent away from the Henry-Reid River the engineers had built a bridge across it. The Red Cross was there with a hot meal for us (you beaut). The first hot meal we had had for about three months, but I’m afraid to say my joy was soon cut short. One of my best friends, Stewart, was sent across the bridge to bring back a hot meal for us in two big Dixies (pans). We all heard this Jap ‘zero’ coming over our heads. Next minute we all heard this huge threatening rushing of air. Stewart would have heard it too. We all hit the ground except ‘Stewy’, being more exposed than the rest of us. He decided to run. The Jap of course was after the bridge. I have only heard one big bomb like this one and I don’t want to hear another. The explosion was enough to split your ear-drums and it could have well contributed to my deafness. The Jap missed the bridge but he got Stewart. They covered up his mangled body with a ground sheet. When I saw what was left of him I cried like a baby.

Before I go any further I would like to say something about Stewart. A brief biography, if you will. Stewart was as some people might say ‘a very good Catholic boy’. He had this fiancée in Australia, when they communicated they called each other husband and wife, they were so much in love. He had everything to live for. Every Sunday the Padre would try to hold some sort of service in the jungle when safety allowed. Stewart was only one of two or three of us that bothered to attend and yet he was the only one to be killed by the bomb. It just goes to show how the good die young.

Getting back to the hot meal again, as I was saying the only other food we used to eat was a very small tin of Bully Beef and two or three ‘dog’ biscuits. A lot of the men couldn’t stomach the Bully Beef, it had pieces of hair attached to it, the sight of which was enough to turn your stomach but it did not worry me, I loved it. If you had false teeth there is no way in the world you could have chewed those biscuits, it was like chewing rocks. But they had plenty of vitamins and minerals to sustain you and that’s all the army cared about.

The next morning when I woke up, my feet were covered in tinea and my genitals were smothered in weeping dermatitis. It was so bad they put me on a barge and ferried me back to the hospital in Jacquinot Bay where I spent the next six weeks being treated for it. I was not the only one in the ward with it, it was commonplace. Very soon after that we were all sent back on leave to Australia (sick again).

The outboard

There was another incident that may be worthy of mention that also bugged me a little. One day my platoon was out on a reconnaissance patrol on the Rabaul side of Tol Plantation – a sort of ‘no mans land’. We came across this small hut, it was not native; it was either built by the previous plantation owner or by the Japs, nobody knew or cared but we did care about what was inside. Would you believe it held a beautiful big outboard-motor?

‘Muggins’, being probably the biggest and strongest in our platoon volunteered to carry it back, so passing the Bren onto my no. 2 of mates then struggled it up onto my back. We then beat a hasty retreat back to our company’s perimeter some miles behind.

By the time we got back I was just about buggered and dumped the bloody thing on the ground, breaking off the fuel line that goes into the carburettor. Mick did mention it to me but it would not have been all that hard to fix. He being an officer there was not any problem for him to take it back to Australia if he chose.

When we did in fact all arrive back in Brisbane he sold it to our company commander for X amount of money. Both Mick and his wife invited the whole platoon out for a night in Brisbane, all except me; I was down with a bout of Malaria at Greenslopes Hospital just out of Brisbane.

I thought at the time and even today still think that seeing as how I was the silly big idiot who carried the bastard of a thing all the way on my back the least they could have done was to wait another week until I came out of hospital. Maybe it did not suit their itinerary. I don’t know, what do you think?

Tol Plantation

Before I go any further I would like to tell you about that massacre at the Tol Plantation. But first, to the uninitiated, New Britain is part of Papua New Guinea and Rabaul used to be the capitol of New Britain. Now when the Imperial Japanese Army invaded Rabaul the small Australian garrison was very quickly over-run. Very little is known about what happened to those who stayed there but we do know that about 150 of them endeavoured to escape before they were finally caught up with at the Tol Plantation.

What happened there was leaked back later by natives who witnessed it. Every one of them was used for bayonet practise by the Japs. Not one survived.(Note This is not so, as family members of the three survivers have indicated in the comments below. But it is what Ross believed and that is the point.)

Their bodies were discovered sometime later by some coast-watchers still laying down where they had died. Now there is no way in the world I could stick a bayonet into some poor buggers’ belly unless it was strictly in self defence.

The Japs have always maintained they have no respect for anybody who surrenders: it is not part of their Bushido Code. But that is so much crap because they were equally as cruel to civilians, if not more so. The Bataan Death March ‘the Rape of Nanking’ in China in 1937 where they raped all the young girls before killing them, they have said themselves they used to abide by the three ‘alls’. Kill all, loot all, burn all. It has been documented that two big Jap officers there had a competition between them to see which one of them could decapitate the most Chines in one hour with their Samurai swords. They were both executed at wars’ end.

It is also documented that they not only raped but they also tortured men, women and children in the most sadistic manner imaginable, thrusting sticks up into people’s private parts. Staking out women tied with their legs agape so they could be raped continuously by any passing soldier until they were dead. Burying people alive: forcing fathers to rape their daughters and grand-daughters; etc, etc; and laughingly enjoying themselves immensely. Killing, raping, sodomising, and torturing more people in Nanking than in Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined. It is estimated that about 300,000 Chinese civilians were killed in Nanking alone.

It is also documented that many of the women who were raped became pregnant and destroyed their babies at birth.

Even today, two or three generations on, if given the opportunity they would be just as big a pack of cruel sadist bastards as their grandfathers (it’s in their blood). Call me racist if you will but I am speaking the truth. Now to the sceptics, the bleeding hearts and the ‘do-gooders’: You would probably like to think of me as a racist but before you jump to conclusions I have this to say to you.

Get yourself down to Dymocks books Store in Sydney. Buy a copy of the ‘Rape of Nanking’. If you have the stomach to even get half-way through that book then and only then can you call me a racist.

Victory

Soon after arriving back in Brisbane the Japs threw in the towel and what happened next has got to be seen to be believed. Every night for the best part of two weeks there was dancing in the streets: no cars, nothing except people; Yanks, Ozzies, men and women; dancing, kissing, hugging, fraternising, you name it. Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, everywhere. Ask Joan, she was part of it.

Finally I arrived back in Sydney and became very disillusioned with the army; both the media and the people were saying that young Australian lives had been lost unnecessarily. Islands like New Guinea, New Britain, Bougainville and Malaya had long been bypassed by the Americans in their island hopping campaign on their way to get bases nearer to Japan for their B52-bombers.

All the Japanese that were ‘holed up’ in these islands were a threat to nobody. They couldn’t go anywhere; America had control of the sea and the air. They were virtually self-contained prisoners of war; left to wither on the vine, as it were; growing vegetables and whatever. We would have been much better off fighting alongside the Yanks at Iwo-Jima and Okinawa.

What sickens me most is that solders like Stewart and Col Goodenough did not lose their lives fighting for Australia; they died for a lost cause. They died for nothing. But ours is not to reason why, ours is to do and die.

Anyway, I soon forgot about all that because I came down with my third bout of malaria and was hospitalised.

Let me tell you how malaria is transmitted. There is only one mosquito that can give you malaria and that is the Anopheles and even then it’s only the female of the species. They first bite an infected person, and then when they bite you they inject this fluid in their system into your body to stop your blood from congealing. It is then that the malarian parasite enters your bloodstream and very soon after you have malaria.

When I came out of hospital I was transferred to a transport unit at Glenfield and one night I went on leave to Luna Park. I met this sheila there, she told me her name was Joan. End of story.

Ross Smith

Footnotes:

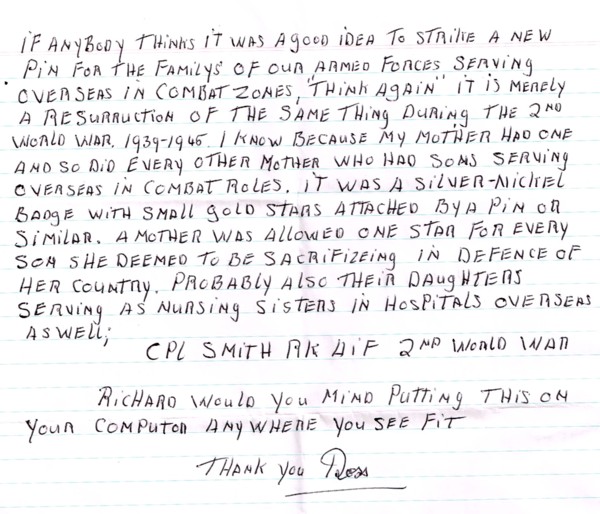

Family Service Pin

Americans

When Singapore fell to the Japanese our prime minister at the time, John Curtain, realising that the Japs would soon be on our doorstep, sent an urgent request to Winston Churchill for assistance. But England had their ‘backs to the wall’ and the request was denied. It was then that John Curtain made a speech to the Australian public saying from now on we must all look to America for our salvation. He also demanded that a large contingent of Australian troops, en-route from the Middle East to Burma to fight for England be immediately re-routed to defend Australia.

Also in 1942 the Yanks ‘hit our shores’, commanded by one flamboyant General Douglas MacArthur, to be used as a base area before being shipped to places like Guadalcanal and Saipan. Their arrival was very much welcomed by us because without them we would have very quickly ‘gone under’ to the Japanese. That was our initial response by all and sundry; but there were other benefits to be obtained, especially by the women who thought all their birthdays had come at once.

There was of course a lot of rivalry between the American and Australian servicemen, with the Aussies at a great disadvantage. First off there was the typical Australian soldier, shabbily dressed, six bob a day, rough as guts and twice as salty.

By contrast the girls had never seen anything like this before in their whole lives. The Yanks wore these magnificent tailored uniforms; chocolate and fawn in colour with nice brass buttons on the officers. A very nice American accent, well mannered, plenty of money and they knew how to treat a lady.

Then of course there were the sailors, also immaculate. We used to call them Gobs. Gobs was slang for mouth (everything is big in Texas). Then there was the Battle of Brisbane when two trainloads of Yanks and Aussies were temporarily side-tracked opposite each other just outside of Brisbane. At first there was friendly repartee which soon developed into a slanging match and then into open violence, when a couple of drunken GI’s started slinging about what they were going to do with our girlfriends while we were away in New Guinea. It was a real free-for-all in which several were killed and many injured before both the civilian and military police were able to restore order.

Ross Smith