I grew up in semi-rural Thornleigh on the outskirts of Sydney. I went to the local Primary School and later the Boys' High School at Normanhurst; followed by the University of New South Wales.

As kids we, like many of my friends, were encouraged to make things and try things out. My brother Peter liked to build forts and tree houses; dig giant holes; and play with old compressors and other dangerous motorised devices like model aircraft engines and lawnmowers; until his car came along.

We both liked homemade rockets and explosives; but our early efforts, before the benefits of high school chemistry, generally resulted in the rockets exploding and the explosives fizzing. You can read more about this in the article Cracker Night (click here).

Commercial firecrackers and gunpowder were generally more successful; although home-made nitrogen triiodide was always easy, and zinc dust and sulphur makes a pretty good rocket fuel. We also had some fun with large gas filled balloons; and various means of firing marbles and other projectiles.

Fortunately we had 'the sheep paddock', forming part of the property, for such experiments. We only set fire to it once or twice when the grass was particularly long and dry.

There was never any suggestion from parents that we should not be wiring up electric motors or installing flood lighting to repair cars under. We both had a healthy respect for high voltages and seldom got a 'shock'.

We are both still alive and were never injured by one of our experiments (by other things occasionally). The parental policy was that we were warned and asked what safety precautions we were taking. After all, we had seen first hand what happens when a length of copper wire falls across the 33KV local distribution grid and shorts it to the street lighting; talk about loud; and dark that night! See the note below.

So we generally took appropriate precautions with things that might explode; as when Peter successfully warned his young apprentice Ian to run! just before his steel compressor bottle exploded, rattling the neighbourhood windows. The neighbours were used to the occasional window rattle; and once or twice a hole or two.

This experience with potentially exploding things came in handy many years later when I worked in research at British Steel. I was employed as an economist, to analyse the value of the research, but quickly got drawn into active experimentation.

My colleagues and I in the 'Forward Technology Unit' decided to test the practicality of an idea that one of them had for inexpensive explosive forming.

Explosive forming involves setting up a high pressure shock wave in an incompressible fluid; we used water. The shock wave needs to be of sufficient intensity to make a steel plate instantaneously plastic, like putty, and so form it to the shape of a mould. But it needs to be not so powerful that it destroys the apparatus.

Needless to say, the trials involved heavy muffled thumps and occasional flying bits. We set this up in the mini steelworks within the BISRA laboratory complex at Battersea in London.

When the safety committee turned up, summonsed by occasional louder detonations within the bowls of the complex, they found us helmeted and safety goggled behind sandbags and an upturned table.

A very long stick was connected to the heavy steel apparatus through a hole in the very stout wooden box that enclosed it against shrapnel. Turning the stick opened a tap that initiated the process. Sometimes the box would then leap into the air. For some trivial reason about it looking 'Heath Robinson' they ordered us to desist!

Later we turned our attention to another idea that involved, as a side effect, consuming a foam containing, among other things, an isocyanate in a very high temperature furnace.

Although we assured the committee that it was properly ventilated and it was unlikely that at these temperatures any cyanide gas would be released into the Lab, or the London air, they called a halt to that too; but not before some nice samples had been made.

Radios

From an early age I built crystal sets then repaired five valve radios. While still in primary school I had mastered the secrets and practicalities of the superheterodyne.

And by early high school I had an unlicensed ham radio; an old No19 tank transceiver, surplus from the War, that I modified extensively; removing the very high frequency section and adding a power supply; in an attempt to communicate with radio amateurs overseas.

Although I could easily communicate with the school cadet radios and our own walkie-talkie, making myself heard overseas proved elusive; despite increasingly long and elaborate aerials.

The basic short wave transmitter was based around one of the famous 807 transmitter valves that delivered about 8 watts.

When I tried amplifying my signal to around 50 watts (four 807s in push-pull); enough power to light a florescent tube held near the aerial, I broke into the local TV signal in the surrounding area; to the consternation of the neighbours.

I promptly shut everything down; but lived in fear of the PMG inspectors for about a month. The Postmaster General's Department was at that time responsible for allocating, regulating and policing the radio spectrum. Hunting down illegal users,apocryphally using direction finding vans, was a specialty; probably a remnant of wartime spy-catching.

There was as yet no Citizens Band (CB radio) allocated and today's mobile phone bands were in the even more distant future.

I'm not sure how many people were affected. TV sets, black and white of course, were expensive luxury items and it was said, perhaps maliciously, that certain people bought a roof aerial, the outward appearance of TV possession, before actually possessing a set.

TV

Although my father worked for a company that had a division that made them, and could get a set at company prices, we were late TV adopters. My parents thought it too distracting when we were students and it was generally referred to as the 'idiot box'.

When we finally got a set it wasn't supposed to be turned on until the ABC news at 7:00 pm. But once we had it my parents were like 'poker machine addicts'. 7:00 became 6:30; for 'Bellbird' then 6:00 at the weekend for 6 O'clock Rock. Before we knew it we were watching commercial channels like 'The Gordon Chater Show'; 'Mavis Bramston'; and Bandstand; just for the go-go dancers.

If this sketch {youtube}PHvxgGfUcXk|600|450|0{/youtube}

(I'm sorry but it's no longer here) from Mavis Bramston seems incomprehensible, have a look at this one (that it was a parody of): {youtube}KCcZyW-6-5o|600|450|0{/youtube}

That an ancient comedy sketch, that is no longer funny and is interesting only in its historical context, should be taken down for copyright reasons is indicative of what's wrong with ridiculously long copyright protection. See also my comments here.

You see TV once had to be educational. Next time you are in a plane and consider the wings out of your window you will know how many thousands of tonnes of aircraft stays in the air.

Click, click, click, went the golden knob of the turret tuner on the front. Three channels to choose from until 1965 when ITS (channel 10) made it four. How could we decide?

No remotes in those days; only 16 or so valves to do all the electronics. Complicated but comprehensible. Lots of scope for tuning it up with a non-magnetic screwdriver made from a plastic knitting needle. No colour information processed through a delay line or colour burst information during the fly-back synchronisation then; PAL colour was not to come until 1975.

Colour increased the complexity enormously but with a little effort, mending a TV was still within the grasp of a real dad. TVs, like Hi Fi amplifiers and tuners, still came with a circuit diagram in the manufacturer's instruction book so that a moderately skilled owner could repair them.

But an oscilloscope now needed to be added to the tools required. Mine is still in a box under the house; I can't bear to throw it out; its beautiful. I built it from a Heathkit, when I lived in New York, to replace an earlier home-made one left in Sydney.

Today not even a real electronics engineer could explain the finer circuit details. The processes take place incomprehensibly by means of thousands of transistors etched onto tiny microchips surface-mounted robotically onto circuit boards that are so complex that only a computer can design them.

The days of etching your own circuit designs onto copper laminated boards are long gone.

The signals are no longer analogue. TV, digital radio, phones and almost all electronics employs computer technology, using programmed software and firmware, that is in turn designed and developed using a computer.

Now its impossible to open the back of a TV; swing out the boards; and go to work with a multimeter and soldering iron.

We just throw away the whole sub-assembly, or more often whole TV; just like a computer. Some of that fun is gone forever.

Instead we have the fun of creating programs for computers; and websites.

Cars

I learnt to drive in my mother's car, getting my licence a week after my birthday.

My father taught me, and later my brother, to drive although Peter didn't require much teaching for the reasons discussed later.

My father had taught Australians, Canadians, South Africans and Poles, amongst others, to fly fighters and fighter bombers in the Empire Air Training Scheme in Canada, in the latter part of the war (WW2). That's how we ended up in Australia.

As a result we learnt to drive like fighter pilots. We were shown how to get into and out of skids. Independently we discovered 180s and 360s.

Peter even showed a hapless hitch-hiker his roll-over technique. He now denies this; claiming instead, and I quote, that he demonstrated: 'his clean off the suspension on the curbing technique'. The hitch-hiker may not have appreciated the subtleties.

When I got my licence Peter, who is two and a half years younger, promptly bought an Austin Seven; in pieces; for £10; plus some more pounds, to a final total something less than £70 'on the road'.

Actually, there were eventually parts for about three Austin Sevens. We assembled an engine, chassis and drive chain, it had a fabric universal joint, and he put a seat in place on the chassis so he could drive it.

And drive he did; around and around the house; to the detriment of the sandstone side steps, and the back lawn and terracing.

By the time he was old enough to have his licence he had restored the Austin Seven sufficiently to get it registered. It had, on occasion, been taken out on clandestine test runs, up and down Pennant Hills Road and around adjoining streets; but not very surreptitiously; as it initially had a defective muffler, when fitted at all, and until Peter re-ringed it it blew clouds of smoke .

At first the battery was the most expensive individual component in the entire car, in due course surpassed by a new windscreen. The electric self starter, to replace hand cranking, was an add-on that sat over the flywheel near the passenger's feet.

An Austin Seven - Peter painted his red

There was a COR garage at West Pennant Hills that had our custom.

COR, Commonwealth Oil Refining later became British Petroleum. Due to road widening the garage moved around the corner and was rebadged green and yellow. The proprietor, Ray, lent us specialist tools; but he would only lend them if I took responsibility. He told me that Peter and I were as different as Hitler and Stalin. I never worked out who was who. I was afraid to ask.

Initially my father had frequented a mechanic's garage in Pennant Hills. The garage was of an older generation in contrast to the new glossy ones. It sold Vacuum Oil products, under a red flying horse logo, later renamed Mobil.

The building, not the village setting, which bordered on bucolic, smelled of oil and resembled the one in the 'Great Gatsby' (the movie); unfortunately without Karen Black.

It was modern enough to have three electric pumps, one for 'standard', another for 'super/Plume', and a third smaller one for dieseline on the pavement outside; but kerosene, for heating and so on, was still pumped the old way; by a handle, into a glass top like a water cooler marked off in gallons; from which a tap allowed it to flow down the delivery hose.

It was on the eastern side of the main shopping village, but was soon lost under successive road widening. It disappeared along with the the Radio shop where I sometimes picked up old radio chassis for parts.

What men do

My father and his brother were electrical engineers.

Their natural father James W Lawson McKie had also been an engineer in Newcastle on Tyne in England and managed a firm that made electric traction motors.

He is, or was when I visited it in the 70s, recorded in the museum there as an early pioneer of wireless. He installed a substantial wireless mast in their garden but died when my father was eight.

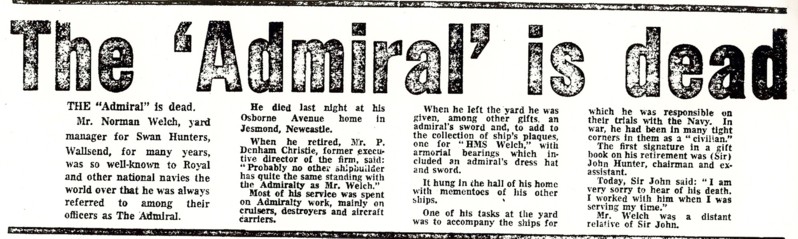

My grandmother remarried. My step-grandfather was the Yard Manager at the Swan Hunter Wigham Richardson Shipyards at Wallsend, another engineer.

The yards built ships for the Navy during the war, three destroyers and a cruiser as well as many smaller vessels like mine sweepers, and he was nicknamed the Admiral, my father loved him and used his name, Welch, for a time.

Although both initially worked in power engineering at CA Parsons, Stephen, my father, became more interested in radio, radar and electronics as a pilot in the RAF; while Jim, his brother, joined Glovers Cables when he was demobilised from the Army where he had been a REME officer in India.

Glovers manufactured high voltage gas filled electricity transmission cables and he represented them, and after a merger, BICC, in Australia until he retired.

While both were senior managers, they built rather than bought Hi Fi systems and speaker enclosures and were generally skilled at most trades like repairing radios and cars, wiring, plumbing, carpentry and so on. My father held several patents and designed advanced electronic equipment.

They were not alone. One of our neighbours was a civil engineer who built extensions to his house; repaired his car; made very beautiful wooden toys for disadvantaged kids; and was for a time commissioner of scouting. The other neighbour was a plumber who did a bit of small scale manufacturing on the side.

My mother's father was a plumber too, as was his brother and his father, who had a manufacturing business in Newcastle. They all ran their own businesses. My grandmother's sister married a Dane who also owned a substantial plumbing business.

My maternal grandfather was a Major in the Home Guard, possibly as he had been a Military Medal winner and senior non-commissioned officer during the first war (WW1).

In his business he manufactured locally designed 'mills bombs' for his Home Guard company's use, against their possible need in the event of an invasion.

My mother's uncle Paul was recognised, after the war (WW2), for his efforts in the Danish resistance blowing up German supply trains.

As an aside, one of my mother's favorite stories was how they retreated to the basement during an air-raid only to be told by grandpa, after the 'all clear', that it was just as well they weren't hit as they had been sitting on the crates of mills bombs.

Peter and I grew up with an understanding that men could do all these things.

It came as a great shock to me to discover that my fourth class teacher did not know how to wire a three pin plug; obviously a pretence at a man.

I did very badly at school that year; particularly after a 'show and tell' when he mocked me for claiming that it was possible for a rocket to put an artificial moon in orbit around the earth; telling the class by way of correction, that the Bible makes it clear that men can't leave the earth; and God will prevent such a thing (as at Genesis 11:1-9).

But among my father's interests was amateur astronomy. I had a notebook that he used to write in when he explained things to me that included a beautiful diagram of projectiles tracing parabolic paths at greater and greater range until the arc exceeded the curvature of the earth; at which point, having also cleared the atmosphere, the projectile would keep on falling for ever. It would be in orbit. You can quite easily calculate such things as the required escape velocity; at least my father could at the time.

According to Mr Perkis (Perkins Paste), who didn't even understand Ohms Law, I was a weak-minded victim of science fiction comics, radio or movie serials. I was mocked. I was mortified. I cried bitterly.

Then I wasted the rest of the year refusing his ridiculous homework and truanting. This became easier when we were moved to an overflow classroom at the nearby Presbyterian church; the school having been unable to keep up with post-war immigration and the 'baby boom'.

I was nicely vindicated in the satellite matter too just five years later when the Russians launched Sputnic 1. By then I was in high school, on my way to University. But I never went back to Perkins Paste to rub it in his face, I just smiled: what a fool he must feel!

I imagine that by now he is gone to dust again.

More about School

I had Perkis for two years and was caned a number of times during that time. But I wasn't Robinson Crusoe in that; he even caned at least one girl.

The most notable occasion was when he had organised a 'detention' to rebuild a fence that we (children) had collectively destroyed; playing 'Bengal Lancers' with some long steel poles that once held the wire around the tennis court.

Several children to a pole, we charged the fence knocking out one paling after another; until just the posts and horizontal bars remained.

Perkis was supposed to be supervising us and desperately undertook to repair the damage.

This involved himself and the ten-year-old boys sawing replacement paling lengths out of a pile of timber from the recently demolished (and recently rebuilt) Girls 'dunny' (toilet block) at the school. Children then transported the very orange planks (the toilet block was painted orange, at least on the outside) down to the Presbyterian Hall; where Perkis nailed them up in place of the broken palings.

A couple of friends and I had skipped off for lunchtime. Probably down to the the local bakery; the fruit trees on the railway embankment; the big culvert; or somewhere else more amusing. But a friend and I got caught returning to school. I had also, undiplomatically, mocked the 'girl's dunny fence' with its bent over nails; and orange palings that weren't even nailed-up straight.

I got 'six of the best' for that - three 'cuts' on each hand.

Apparently the Presbyterians took a similar view about the orange fence; it didn't last long. Thinking back, I realise that the reason the boys could cut it so easily was that old dunny dated back to the previous century and the cladding timber was probably Australian Red Cedar. Today it is very valuable. If it had survived it would probably be the most valuable fence in Thornleigh.

One special friend at school was Bob Piper. Bob has now added a little more: "I remember the bengal lancers, fence palings episode well. I was one of the ones that pissed off and came back when it was nearly finished."

Bob has written a story available, on line, about another teacher we had, Mr Pallane (Sabre Jet). (See Bob's story 'DOROTHY’S COTTAGE' about half way down the PDF linked here). Mr Pallane gained additional qualifications and moved to my High School where he taught me English in third year (year 9).

My previous English teacher Dr Sutching was a good teacher, from whom I learnt a lot, but had consistently marked me down because I couldn't spell (I've probably misspelled his name); and because he was fighting a class-war against people like my factory-manager father; and especially my English Conservative Alderman grandmother, who had addressed the school during a visit to Orstralia.

He even put one of the boy's up to giving an anti-Imperial speech on Commonwealth Day. Resulting in the Headmaster (the Boss - Mr Pearson) ordering me to turn off the microphone. I was in charge of the sound system.

But Mr Pallane greeted me like an old friend and encouraged my writing so that by the end of that year I was second in the class; but still couldn't spell very well. There was then a public examination, 'The Intermediate Certificate' after which many children left school. I did very well in English and went on to matriculate to University.

I agree with Bob - he was an excellent teacher - despite a reputation for a violent temper.

In reminiscing about the now long gone Thornleigh Public School I looked up some old photos on-line and found this one (click on it to follow the link).

This was on my way to school.

Across the intersection is Trace's Produce store. It provided everything from seed for local farmers, to coal, coke and timber for fires. They had big bins of dog biscuits that we children occasionally stole to chew on.

To keep down the rats and mice there were lots of cats and if you wanted a kitten he would deliver one with the firewood.

The office was to the right of the front door and on the counter was an electric bell push to summon the staff or 'Tracy' from the back of the building.

If the office was empty we would dodge in the door and ring the bell as we passed. With any luck he would come raging up from somewhere with a fearsome sack-hook in his hand to chase us off.

You can see that this picture was taken a few years later, when I was already in high school. There is now concrete curbing outside the upholsterer and on up the road. It looks quite new. The street lights are the mercury vapour ones that Peter's balloon blew-out (see below).

In the far distance you can just see two service stations (BP and Esso) and beyond that, around a bend, was the school. The Esso had big tiger footprings painted on the forecourt and the slogan: 'Put a Tiger in your Tank'. They gave away tiger-tails to attach to your petrol cap.

When they were building one of these stations they dug a huge hole for the underground tanks. But because it was solid rock in that location they needed explosives. Big heavy hemp mats were laid over each 'shot' to stop flying debris. We stood down the road and watched the process; it was wonderful! Much better than our own feeble efforts.

Behind the photographer and to the left is Barnes' Bakery. Note the telephone number with the WJ prefix ( = 84 in those days - it's changed).

Notes:

The 33 kV Explosion

This resulted from a balloon experiment.

Peter had saved up to buy a very large rubber balloon which he had filled with town (producer) gas from an outlet the laundry using a pump. This gas still had a considerable hydrogen component, along with carbon monoxide, unlike today's heavier natural gas. But having no suitable string he decided to use the copper wire from an old radio transformer that I had previously broken open.

I had quite a number of these and every now and then took one apart as a source of wire of various gauges; particularly for our homemade telephone system to Colin next door; for radio aerials; for winding coils for buzzers; rewinding my burnt-out Mechano motor and so on.

Copper wire of a gauge thick enough to restrain a large balloon comes from the low voltage windings on such a transformer. It's quite heavy and the balloon hadn't risen a lot higher than the trees , maybe 60 feet (20m) or so, when it wouldn't go higher.

That's when I discovered my little brother repeating Benjamin Franklin's famous lightening experiment; holding the end of a 60 foot lightening conductor in the back garden. Several people have been killed trying to repeat this experiment (read more).

I claim to protect him from being fried; he claims out of sibling maliciousness; I reached above his head and rapidly bending and straightening the wire (as one does) broke it.

The balloon then rose ponderously; higher and higher; at the same time being carried by a light breeze in the direction of Pennant Hills Road and the railway cutting.

The trailing wire cleared the house; then hovered over the cars and trucks on the main road. But continuing to drift westwards there was no chance that it would clear the high voltage power lines running between the road and the railway.

A spectacular two second display of sputtering sparks and sheets of blue green flame ensued, as the dangling copper wire first struck, then fell across the high voltage lines; was vapourised; and became plasma.

The noise was remarkable too; very loud. Then everything electrical stopped.

The local grid protection breakers kicked-in and the power went off for a minute or two. Then just as quickly everything returned to normal.

It's amazing - those 33kV wires are still there the same as ever - but the streetlight has changed. And the road is twice as wide.

The railway cutting is beyond the fence.

Householders called out by the noise returned indoors to continue what ever they had been doing. All except our father, who was working from home. He circled the house and finding us acting nonchalantly; in other words suspiciously; demanded to know: 'what have you done this time!' Why immediately assume it was us?

Remarkably he was then more concerned about possible subsequent safety issues: remnants of wire dangling from power-lines; or the ongoing path of a balloon trailing copper wire. But everything had gone; the balloon exploded and the wire vaporised! I don't recall any punishment at all.

That night all the mercury arc street lights on the main road were off. The 33kV had been shorted down to the adjacent street wiring and the fuses protecting every ballast in that section had blown.

Innocent little Peter asked the team that came to replace them what might have caused it? One bloke said: 'could've been a tree branch or lightening...' Peter said: 'what are you doing with the broken ones - can I have one' The bloke said: 'Go for it!' So we took several bulbs and at least one ballast.

So that's how for many years later we had a brilliant blueish street light high on the side of our house (we just replaced the fuse); enabling us to work on our cars in the garden after dark.

Comments (too long for below)

Hi Richard,

Great article. I tried to post the following comment in reply but your side advised me the comment was too long.

Bought back many memories and good laughs. I agree that we boys had a devil may care attitude toward experimentation. You may recall another Pennant Hills local Paul Cordony (Cordony hairdressers), blew off part of his hand building a pipe rocket launcher. The reaction was fear of getting into trouble rather than concern for his hand.

Post boxes did not fare well from constant youthful terrorist attacks from tuppeny bungers.

I had two 1932 plymouths. One capable of driving and one for spare parts. Before my licence of course. All repairs and alterations tested out on the public roads.

In part, my frustration with the teachers led me to depart Thornleigh, with my well earned bag of marbles won down by the dusty bell post, to five train stops away, Marist Brothers Eastwood. I found Catholicism as incomprehensible as I did with the Thornleigh scripture class. When my teacher (a marist brother) suggested we are all made in the image of God, and I asked if God was a monkey, I was immediately branded a rebel. Earned me six of the best as well. I now realise that maybe I was forward thinking.

I have often wondered what path my life would have taken if I would have been encouraged to pursue maths rather than to be sidelined to give everyone equal airtime. I am however actually very happy the way things turned out for me.

For me, sport played an important role. Team sports, being a desire to be accepted, and wanting to contribute better than my mates, spurred me on. It also formed lessons that I unwittingly adopted later for business.

I think the teachers actually did us a favour in that my determination to achieve was greater for not wanting to accept the norm. The fact that I was constantly reminded that I was a wog (not by the teachers) added to an unconscious desire to do better. The day to day quest to find challenges, and its associated mischief, left no time to contemplate self pity. It was a very healthy and uncomplicated time of my life and one I think back on fondly.

Cheers

Leslie