Appendix - A commentary on the past

The past is done and dusted. There's nothing we can do to change it, and so we are obliged to embrace it as the means by which we got to here, the present.

So why bother about the past at all?

My family, for as many generations as I can trace, came from Northern England and before that Scotland with an Irish admixture, and possibly, one line from France in 1066.

I've tried to make this more than a simple tale of men begetting sons as in the first book of The New Testament that begins with the lines:

|

The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham. Matthew Chapter 1 |

Yet that's an all-time best-seller. So, to begin about begetting must be de rigueur and infinitely better than: "It was a dark and stormy night..."

I take my hat off to the author of Matthew. I had trouble going back further than six generations, let alone his 43 back to Abraham.

The author of Luke's Gospel came up with an entirely different genealogy for Jesus (Luke 3:23), this one via Nathan rather than Solomon, taking an extra seventeen generations back to King David to account for the actual historical time difference of around a millennium. He also went all the way back to Adam - 75 generations, around two thousand years, providing theologians with a date for the Biblical creation.

Despite all this genealogical research, soon their sub-editors would remove the issue altogether (excuse the pun) by changing the paternity of Jesus entirely.

In creating these family genealogies these primitive ancients were labouring under a misunderstanding. They thought they had but a dozen ancestors in six generations - consisting of their father's paternal line plus the women who provided a fertile womb for each man's seed. Bearing and nurturing the man's child was the limit of the woman's involvement. This was an idea that persisted until the Enlightenment and still pervades some legal systems.

The scientific view is that mothers provide half of our nuclear DNA and more genetic material than do fathers to their offspring, due to providing cell structure and the contained mitochondria. The post-enlightenment view, that I hope is obvious to everyone, is that our ancestors include both our parents, then all four grandparents, then eight great-grandparents, then sixteen, and so on.

So, following just one paternal line (Harry begat Sam), does not reflect our true ancestry. The sixth ancestral cohort consisted of 64 individuals who contributed equally to our genes, assuming no overlaps due to cousins marrying. In that time we accumulated 126 ancestors each of whom contributed to our existence and to our extended family.

Good news! When we correct for their misunderstanding of biology Matthew and Luke are not in conflict after all. Thank goodness for that, the Word of God is not contradictory after all, at least on this one occasion. It just seems to be. And a little confused about biology.

This is because continuing the mathematical series by twos (64, 128, 256, 512, 1,024, 2,048, 4,096, 8,192, 16,384... and so on) yields over 17 trillion ancestral lines after Luke's 44 generations. As the entire population of the planet was only about 500 million for most of human existence there was obviously a lot of overlap in these lines, due to distant and not so distant cousins inbreeding.

Six generations ago one line of my ancestry originated among a few thousand people living in small villages and farms in south west Scotland. There were around a thousand people with my name and a lot of distant cousins marrying into each other's families. So by the time I go back ten generations a large number of my ancestral lines will lead to the same person.

This is most obvious when scrupulous records have been kept for a couple of dozen generations, as in the case of European royalty where for generations cousins have been the only acceptable marriage choices.

For example, we know that Prince Phillip and Queen Elizabeth are cousins, both descended from both Christian IX of Denmark and from Queen Victoria. So if Charles traces his genealogy back from either parent he quickly gets to the same pair of ancestors twice over (Victoria & Albert and Christian IX & Louise of Hesse-Kassel). In turn these husbands and wives of the monarchs are related to their spouse a generation or two earlier so many areas of Charles' tree overlap and entangle like a patch of brambles. This is obvious when we consider that there was nothing like a million European aristocrats in the time of Elizabeth I, and just a few thousand produced reproducing descendants. So, unlike a more common person, Charles is related to each his more fecund Elizabethan ancestors many hundreds of times. As their lines die out the in-breeding becomes more intense. He talks to plants.

Likewise, Charles and Diana were seventh cousins once removed. But they were also related to each other more distantly, through far too many different lines and shared ancestors to enumerate here. Had the Palace been looking for another relative for him to marry, beyond the Spencer girls, a quick genetic test would have revealed that thousands of apparently common girls in England, Germany, France, Sweden, Greece, Russia and so on are also distant cousins due to his ancestors exercising their 'droit du seigneur' over the village virgins and their propensity to keep mistresses.

A small village or town or farming community was just like the aristocracy: cousins married cousins. Every now and then people left and formed affiliations elsewhere. Sometimes an entire town was dispersed by war or other catastrophe or simply evaporated when their original reason for being faded. This is commonplace in less populated areas as in the past. Hundreds of towns have disappeared within just a couple of centuries in Australia, much to the distress of those who cling to a single locality.

In a similar way aristocratic families disappear, sometimes dramatically, as was the case of the Holstein-Gottorp-Romanovs of Russia, like all European royals, close cousins to Charles.

Even today the occasional aristocratic European woman or man flouts their marriage vows with a commoner or two; or marries a commoner; or an Australian. In these cases there is a mixing, like paint smeared together on an artist's pallet. If the artist keeps mixing eventually all the colours will have a little bit of each other until eventually there is only one colour.

In ten generations the mixing will be moderate, by thirty generations it will be substantial, constrained somewhat by language and national divides. But in a thousand years we have around two trillion theoretical ancestral lines, many of them bundled through the same person. That's why it's reliably said that every single European is related in some degree to the Emperor Charlemagne, the King of the Franks who died in 814 CE and had ten known wives and concubines and eighteen acknowledged children who themselves had numerous offspring, several of the girls being nuns with sons. Most of us are related, many times over, to these nuns and his other offspring.

So, the authors of Matthew and Luke could have made up almost any genealogy they liked to relate Jesus to David. This was fundamental to their claim that Jesus was the Messiah, because all the major Messianic prophecies indicate the Messiah must be a descendant of King David (Ezekiel 34:23, 37:21-28; Isaiah 11:1-9; Jeremiah 23:5, 30:7-10, 33:14-16; and Hosea 3:4-5).

The more imaginative route and contradictory names suggest that imagination, a knowledge of history and some simple maths complemented Luke's actual genealogical research. According to Wikipedia: 'The composition of the writings, as well as the range of vocabulary used, indicate that the author of Luke was an educated man'. Some scholars believe him to have been a Greek doctor. So, he was unlikely to repeat the author of Mathew's mistake of reporting only 27 generations (less than 650 years) back to King David.

After the actual gap of around a thousand years everyone in the known world was related to King David. As I have said the need to go to all this genealogical trouble lay in the erroneous belief that babies grew from the seed of a man alone.

We are certain that they were wrong and we are now more knowledgeable. Otherwise in-vitro-fertilisation, IVF, would not be possible. The ancients had no idea that babies grow from the living cell of a woman complete with its mitochondria and is 'fertilised' by similarly living chromosomes from the sperm from a man. IVF and chromosomal transfer between cells would have amazed and challenged their faith as it has some theologians, even today. In particular, modern IVF fertilisation procedures make nonsense of the ancient belief, that a god, or some 'spark', is necessary to give 'new life' to already living cells at the moment of fertilisation, traditionally known as conception.

Were either cell dead the zygote and blastocyst would not form. See The Chemistry of Life on this website.

Thus, a few decades later, Gospel sub-editors would make all that ancestry research and imagination redundant by claiming that the father of Jesus was no longer Joseph but God himself. Ancient people, ignorant of IVF and biology, could then believe in the Virgin Birth.

Like Jesus, you and I can certainly claim to be descended from King David many times over, even if you are an aboriginal Australians or North American, provided you have at least one European, Middle Eastern, Asian or North African ancestor.

But this is theoretical. While you can certainly find many lines of inheritance back that far, actually having any of their genes is a lottery. Human beings have only about 20,500 genes. After fifteen generations the number of our ancestral lines substantially exceeds the number of genes we have. Further, genes mutate and evolve regularly. Without an overlap, like in-breeding in a small village or membership of an exclusive religious group or class, some ancestors soon cease to be of any genetic importance. So the influence of a particular ancestor depends on how much overlap there is.

Unless your forebears remained in the same small village throughout the past three hundred years or if you happen to be from a similar in-bred group like European aristocracy or an exclusive religious group, once you get past fifteen generations who your forebears were individually becomes irrelevant - no trace of them maybe left. In the lottery of life your genes could have come instead from almost anywhere, maybe King David.

So, how far back is it reasonable to go? For most of us who are not royal or from an isolated community fifteen generations is the limit before the genetic contribution of some of our individual ancestors is diluted to nothing. Not so culture. Consider an institution like Lloyd's of London. It's over 300 years old, so its founders; their staff; and the original members have been dead for most of its life. Yet it's traditions, memes if you like, go back to it's foundation. So it can be with families. Consider your family religion or your other fundamental beliefs. Consider the Common Law and many societal values and beliefs. Consider science. Consider received history. Such memes can be far more persistent than genes.

Culture and memory

The immediate past is very important to us but there is a qualitative difference between the short-term history we need to make rational personal choices, like expecting my car to be where I left it; to knowing who my great grandfather was; or the causes of the Great War. I have written elsewhere about recorded and oral history. Much of it is myth or tales enhanced in the retelling: 'bunk', as Henry Ford proclaimed.

The first and foremost reason for needing that knowledge of the past that we call memory can be seen when memory fades. We are our memories. These depend on those different structures in our brain that store the past experiences very recent; short-term and long term. Some are responsible for our beliefs and abilities others our relationships and without some basic, primitive memories we can't function at all.

In simple animals the ability to spin a web or run around is due to structures that are genetically passed on, like a leg or an eye, and the abilities that the neurons program for are innate, inherited. But in humans even simple abilities, for example the ability to walk, has to be partly learned. In other words, the brain structures have to be formed or 'stored' in our memory.

If this brain organisation is lost, we progressively cease to exist as 'us' as our old personality disappears, like the Cheshire Cat, until we reach a vegetative state. A person only has a personality by virtue of experience, belief and knowledge. Of course, someone without a mind is unaware of the loss. Medical death is now defined as that moment when the brain stops working with no prospect of consciousness returning. On the bright side, be this loss of brain structure gradual or sudden, we can have no actual awareness of our death. Fade to black.

In our wider perception of the world around us, certain qualities of experience extend over long periods of time, allowing us to expect them to continue, like the existence of our family and our place in it, the laws of physics or even broader: our understanding of 'human nature'. Without a knowledge of the past that misty unknowable place, the future, becomes totally opaque. We need a sense of history to guess at the motivations and beliefs of others and to make judgements about our own purpose and scope for action tomorrow; or whenever.

Unless our families were researched and written about in the past for some reason, most of us have a scanty view of past generations. Maybe our parents took an interest or our grandparents. But most of their tales are memories of people and places distorted by time or stories retold and elaborated to add interest and drama - oral history.

When I was a child, England was a mythical place like Heaven or Treasure Island or the riverside in Wind in the Willows. I had left there when I had not yet turned three years old and had no real recollections, just some photographs and a vague memory of a girl playmate called Lana. This could be a false or recovered memory as it came back to me as I began writing this. Lana if you are out there...

My first reliable memories were of New York on the flight over in 1948; being on the plane; and seeing my Uncle Jim, who met us off the plane, through a sort of hatch at Sydney Airport.

|

|

Early Australian memories - I can tell you a great deal about these photos:

that were taken at - 317 Pennant Hills Road Thornleigh NSW Australia - 1948-49

Front garden: me in the hat from laundry cupboard - The side lawn - sandstone flagged driveway behind

Back garden: vegies - beans, peas, corn, rhubarb - Sheep: Rusty and Michael in the paddock

Peter in the pram - red-back spiders in the wheelbarrow - McDonalds below the back fence

I could go on and on - it's clear as yesterday - yet I remember nothing about England before

Maybe a memory of my mother's father was still there somewhere but soon all four of my grandparents were mythical creatures who inhabited the world of literature - that 'Isle set in a sceptred sea'. It was a land ten thousand miles away that might as well have been on the moon. But it loomed large at school. Australia was still part of the British Empire with Canada New Zealand and South Africa, along with uncountable smaller countries around the globe. The world map on the classroom wall seemed mostly red - well it had a lot more red than green or any other country's colour.

I knew England was a place to be proud of. It had been built by engineers and scientists like my uncle and my father and their fathers. It was a brave country defended to the death by men and women like my mother's parents; where bombs had recently fallen like rain, and my father had landed his Hurricane fighter in flames; where sweets and even butter were still rationed. But at school in Australia, it was not something for a 'pommy kid' to shout about.

When it comes to tracing our family back beyond those we knew and loved, one motivation may be to establish an inherited claim to property or title, for example: Aboriginality; or aristocracy. Another could be 'bragging rights': to be able to claim at parties a descendants' affiliation with their ancestor who achieved something they haven't. A third and perhaps the most legitimate is an interest in how we came to have our particular genetically conferred abilities and appearance; or the source of our family traditions like: a particular trade or craft; attaching value to scholarship or the arts; or our religion.

Sometimes we have old letters, diaries or other family documents that have greater solidity than these fallible tales and comfortable fictions handed down. More reliable sources include contemporary records, some of which may now be found in the Cloud.

In developing this history, I relied heavily on old public records of births deaths and marriages and the British census during the 1800's and early 1900's when individuals were named and their age location, occupation and relationship within the household were noted. Modern censuses are far less useful for these purposes. They collect much more information but individuals can't be identified. The British records aren't complete. In particular, not all deaths are recorded. Also, people occasionally lied about their age or didn't actually know. There was also a reporting problem. To determine the year when someone was born, they should have been asked: "How old will you be this year?" not: "How old are you?" So, there can be a year variation in the date of birth if their birthday falls after the question is asked.

Now there is another even more reliable guide to our origins. Recently, within my lifetime, we have come to understand a lot more about genetics and inheritance, enabling the new art of DNA Ancestry mapping.

DNA Ancestry Mapping

|

|

|

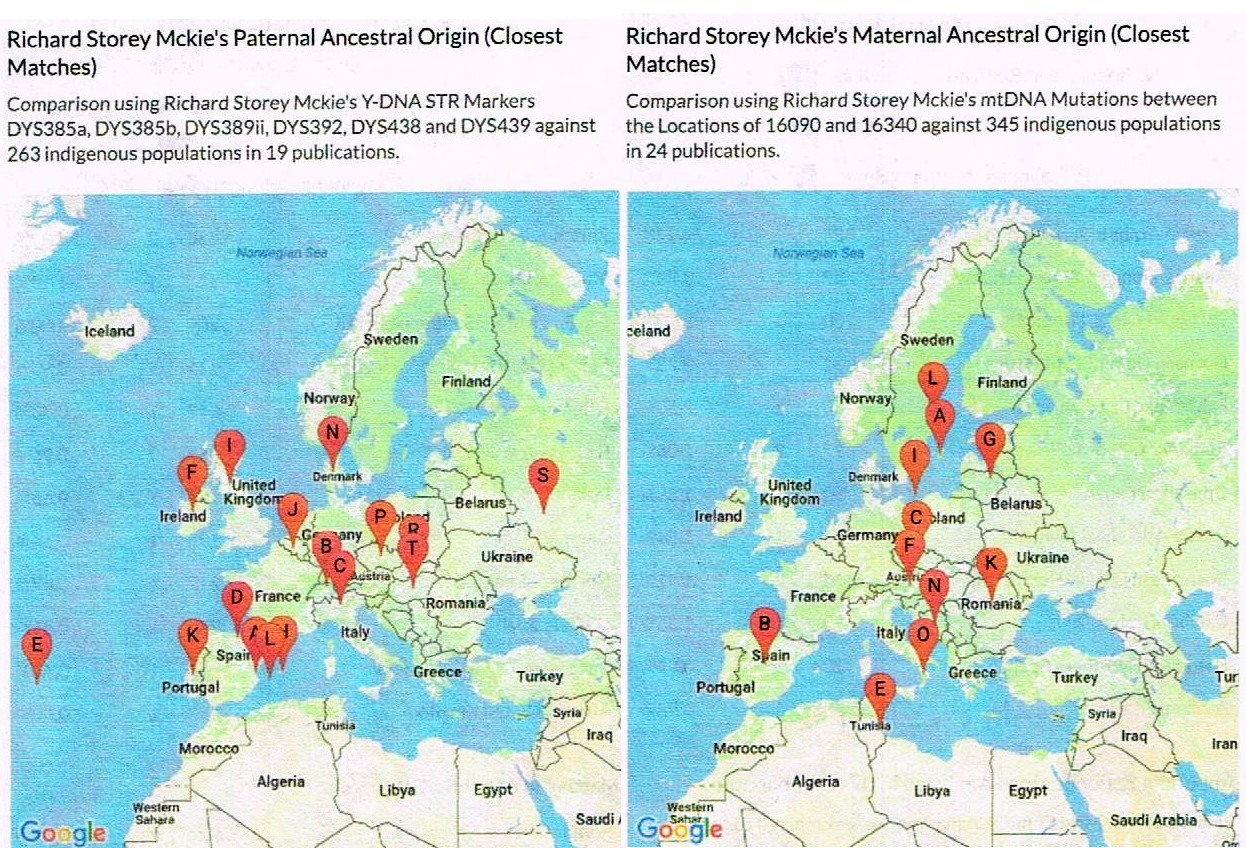

These maps relate to just two of my grandparents. My 'DNA Ancestry' tells me nothing about the other two. To do that I would need to be more sophisticated and look at other gene variants I have inherited from those grandparents. But I don't have their DNA they are dead and burnt, so I would need to go to my first cousins to find a match. This is all just too hard, unless it was something obvious like dwarfism or a cleft palate.

So until the family DNA is mapped generation upon generation and matched to everyone else, this kind of DNA Ancestry mapping will tell considerably less than half the story. It's main utility in this case is to illustrate the end of a genetic line.

My mother was the last girl to inherit her mitochondria and although my brother and I carry it, we can't pass it on. Similarly, my brother's son Daniel is the last to have my father's Y chromosome. The last McKie in this line.

Yet mapping one's DNA is not entirely useless because others in the family can glean something about the origins of a proportion of the less visible genes they are carrying too. Although my daughters don't carry my mother's mitochondria, nor my father's Y chromosome, they have inherited a quarter of their nuclear DNA from each. Somewhere in there is perhaps a bit of Viking and perhaps a bit of Jew. And if they have their DNA mapped, they can learn something of their mother's ancestry.

Like my daughters, my cousins can now be relatively sure of Iberian blood and imagine an early Conquistador landing in Scotland or Ireland as the origin of the ancient McKies.

Thus, in a few generations many people may know a lot more about their real origins and will, hopefully, be less prejudiced about foreigners. No more disliking those outrageous Spaniards or those smug Swedes for us.

As I said at the outset, following back one's family name is equivalent to following back the trail of the Y chromosome. This relationship between the Y and his family name is only broken when a boy is not the son of the father who gives him his name or the family name somehow got changed between generations. Each such break marks the point when a little human indiscretion, act of love, or contractual change took place. Each change marks a point of drama or historical interest in the lives of our ancestors.

Now my daughter Emily has a son and I a grandson. Maybe one day Leander will wonder about his ancestors and how he came to have his mother's family name rather than his father's.

Many of our family values are preserved or reinforced by grandparents. Like me as a child, Leander lives far from part of his family. But I lived far from both sets of grandparents and travelling to see them was effectively impossible for me as a child. Incredible as it will seem to him, there was no Skype and even the phone was prohibitively expensive.

At Christmases and birthdays, parcels containing strange clothes; omnibus books about the adventures of Rupert the Bear; Enid Blyton's Famous Five, Secret Seven and Noddy; or Coronation cut-outs and pictures of the crown jewels (circa 1953) would appear, confirming the grandparental existence.

But there my ancestors remained, like characters in the A A Milne; or Ratty and Mole messing about in boats; or in Toyland, with Noddy, Big Ears and Police Constable Plod. There children grew up having adventures like the Famous Five or Secret Seven.

On my first return to England in 1974, fresh from high-rise Sydney, via fast developing Singapore, I was amazed. It was quite different to the image I grew up with. I felt that I had somehow been transported to Toyland. Everything was much smaller than I had expected, with row upon row of terraced houses and high-street shops bright with all that red and blue paint, set amid brilliant rolling green fields and copses. It was quiet unlike Sydney, my adopted city, or Australia's rural pallet of blue greys, yellows and ochre; and sunshine.

That reality is different to expectation is a revelation that I have experienced repeatedly since, every time I travel to somewhere new.

Separating reality from myth to discover how my earlier ancestors imposed their personalities and values and advantages on my grandparents and so to my parents and on to me has turned out to be more difficult than I had imagined. And there is more than one skeleton in the family closet.

Leander may one day want to know how those influences, genes and memes, passed down to him, in turn.

As each of us is a colony of cells formed when that one fertilised cell multiplied after conception so each person in turn can be seen as a single cell in the greater corporation that is our society so that it's impossible to separate a person from their environment. In this story I've tried to find out about both.

I've tried to set my father's father's father's father's life in context. But unlike the ancients we know that mothers play an equal or more than equal part in each of our pasts and soon the fathers of our father's fathers fade into insignificance in the sea of our genes, although they ultimately narrow again to just a few individuals and then to just one common ancestor: Y-chromosomal Adam who lived not three to six thousand years ago as the Bible variously asserts, but between 163,900 and 260,200 years ago.

My tale was not a testament, or even a gospel, but I hope you enjoyed it nevertheless.

And so ends this investigation of just one path of my ancestry, my Y chromosome. Like Dorothy on the Yellow Brick Road, it leads all the way from a farm in the countryside to OZ. But if I'd imagined that it would take weeks of research and lost sleep I might never have begun.

Now, in retirement, I continue to take an interest in all things real and imaginary. So, I expect that my grandchildren (and step- grandchildren), as soon as they can reason, can answer simple questions about the real things that surround them starting with: "Where does the bath water come from? Where does the bathwater go? What are those wires in the street? and Where dose the electricity come from?" Just as, when a little older, I expected my own children to be able to tell me how the picture got from a camera in the TV studio to a screen in our living room or how does DNA replicate?

What's next?

There is quite a bit more about my life and My Mother's Family and Emily's mother's family on this website. So, I don't intend to duplicate that here.

Perhaps the main Gap is Julia's mother's family. I'll have to see what can be done about that. Maybe after she retires.