Costs due to transmission

The cost of energy is a fraction of our electricity bills

As consumers we tend to think of electricity as another utility like gas or water or as a fuel source like petrol.

But it is not. Electricity is not a source of energy; it is simply a means of transporting energy from other sources.

Energy is derived from numerous sources by generators and sold into the National Electricity Market (NEM). This energy is shipped by high voltage transmission to local distributors that deliver it to homes and businesses.

Last week the average wholesale price of electricity in the National Electricity Market was 6.6 cents per kWh.

This is the price your retailer spends on energy component of your bill. You will have noticed that they charge you a lot more than seven cents.

Most of the cost of electricity is due to the transport chain; because energy transport is what you are paying for.

If you don’t understand where electricity comes from or how it is transmitted there is a short (simplified) primer on this website: Read More…

Transmission refers to the high voltage grid, the towers you see in the countryside; as opposed to lower voltage distribution, for example in your street. There are five interlinked state-based transmission grids creating this high voltage backbone.

The state-based transmission networks in all eastern states; the ACT and South Australia are linked by cross-border inter-connectors to form a single grid. In geographical span this has created the largest interconnected power system in the world.

The grid interconnections have an increasing role in enabling renewable energy trading across regions.

Very expensive high voltage DC links connect Victoria to Tasmania and part of South Australia. The remainder of South Australia is linked to Victoria using conventional high voltage AC transmission.

Both Tasmania and South Australia have a high proportion of variable wind power; making these interconnects important to ensure local consumer demand can be met when wind is lower than local demand; and to facilitate export of excess power when local demand is low but the wind is plentiful. These two states consequently have the highest cost electricity in the system.

In addition, consumers are paying for a new 500kV grid backbone linking NSW, Victoria and Queensland.

But transmission costs are less than a fifth of the cost of local distribution.

The great majority is consumed by the thirteen linked distribution networks that take feed from the transmission grids to supply electricity to end-use customers.

Grid costs

The highest historical electricity price rises have been in Tasmania and South Australia, where renewable energy is most dominant.

Industry experts generally agree that one of the factors in the big cost increases in the past decade is previous state government action to suppress prices: both by failing to properly maintain distribution infrastructure built in the 1960’s; and through chronic under-investment by government owned instrumentalities since.

Some also doubt the internal efficiency of these companies; relative to private construction or equipment maintenance companies. But this is hard to confirm given the specialised nature of the industry and unique factors in each state and territory.

Recent and ongoing reforms in the industry have released some of these constraints resulting in a lot of remediation. But there is still significant regulatory oversight. Perhaps the most important of these addresses the potential for monopolistic behaviour; particularly in the ownership of wires and poles.

Obviously it is not practical, or economically efficient, to have multiple sets of electricity services running in every street or to have several duplicated high voltage grids.

Rather than encourage many duplications of expensive infrastructure the sensible decision was therefore made, by all Australian governments, to establish a central regulator to monitor and regulate the investment and the charging behaviour of the owners of distribution infrastructure.

This is the Commonwealth administered Australian Energy Regulator, currently being indirectly accused of not stopping alleged over-investment by state owned instrumentalities or, perhaps, the making of monopolistic profits at the expense of electricity consumers (to the benefit of the same local taxpayers?).

Gold plating

There have been accusations of ‘gold plating’ this network. This is taken to mean that redundancy built in to ensure reliability is unnecessary and that the occasional blackout is acceptable.

Most of the grid costs we pay for are for local distribution.

Local low voltage distribution will inevitably fail occasionally due to storms, fires and so on, bringing down or shorting out lines, workers inadvertently digging them up, as well as local equipment failure.

Distribution in new areas is often underground to minimise these failures and to hide ugly wires and potentially dangerous poles. This is one kind of ‘gold plating’ as it is initially much more expensive. In total cost of ownership terms this differs from place to place and underground conduits and cables may well be competitive in many locations.

Certainly in Sydney you don’t need to look far to see poles, cables and insulators in need of replacement. But are the lines-persons who maintain this infrastructure efficiently managed? Is there excessive management overhead and/or ‘featherbedding’? Is the technology still being deployed the most cost effective?

A good deal of the recent increase has been attributed to upgrades to transmission infrastructure.

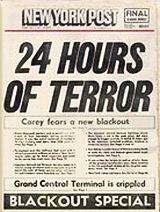

Redundancy in the High Voltage grid is more critical. As failures in North America and New Zealand have demonstrated, such a failure can take out an entire city.

I was in New York when this happened in 1977. Try walking up and down a high rise staircase with a candle; to and from an apartment where the toilet no longer flushes; there is no water or lighting; and the food in the refrigerator is going rotten. Trains stop between stations. Lifts, lighting and air-conditioning cease to work in high rise commercial and residential buildings. Petrol pumps stop working; as do ATMs today - back to the cash economy - if you have some.

Sometimes this outage lasts for hours, or days, by which time water supply, sewerage and communications will be compromised. Business computer systems fail as UPS batteries are flattened and even back-up generators run out of fuel.

Lawlessness can erupt. People die.

The costs to the economy of such a failure are measured in hundreds of millions, even billions, of dollars.

Experience has revealed additional risks to electricity grids that were not evident when they were first conceived.

Australians consume more electricity per capita than most other countries and the east Australian high-voltage grid is now one of the largest in the world. As the complexity of the grid increases, so the risks surrounding the failure of a critical link increase.

Each link in the grid needs to have capacity to supply at the maximum demand. As described in the 'primer', when currents increase more energy is lost to the environment as heat. These losses rise exponentially with current.

As a result of higher peak currents the grid becomes more expensive.

Either:

- users pay for excessive amounts of energy wasted as heat; and the risk of high current tripping (breakers opening) becomes unacceptably high; or

- links need to be duplicated; or

- wires and cables need to be replaced with larger diameter, heavier ones with more substantial supports; and/or

- voltages need to increase; again with more expensive towers and new transformers.

As power-stations become more remote, and interstate sharing increases, voltages are being increased to reduce losses. This involves taller, more costly, towers and a greater risk of insulation failure. There has also been the need for some expensive DC links.

This is necessary partly as a result of higher levels of fluctuation and current peaks due to alternative energy interstate and irregular demand.

Electrical breakers in the grid protect against wires melting (blowing out) due to surges of excessive current. If this happens there is a blackout in the affected area.

This could be something as rare as an induced DC pulse, caused by a strong magnetic pulse emanating from a solar flare or a super nova. This has the potential to bring down or destroy AC components. In 1989 a solar flare caused such a DC pulse and six million people in Canada to lost their electricity. Read More...

I don’t think reasonable measures against these possibilities can be called ‘gold plating’; unless this is code for ‘Union feather bedding’ in the government owned instrumentalities. Maybe this is what the PM meant?